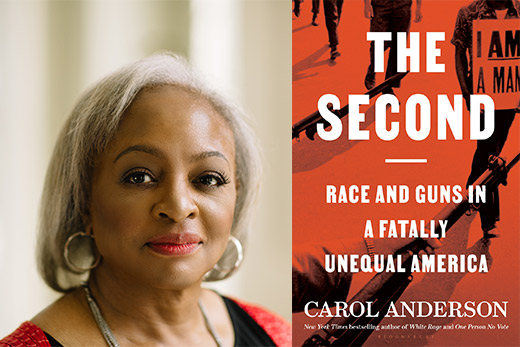

Emory College historian Carol Anderson has focused much of her research on how racism and racial inequality affect the creation and unraveling of U.S. policy.

When police killed Philando Castile, a Black man with a license to carry a gun, during a 2016 traffic stop, the Charles Howard Candler Professor of African American Studies realized she had not applied her skills to answering a specific, constitutional question: Do African Americans have gun rights?

Her new book, “The Second: Race and Guns in a Fatally Unequal America,” answers by arguing that Black Americans have endured a fractured citizenship since James Madison drafted the Second Amendment primarily to ensure white men could suppress potential slave revolts.

For instance, she asserts that the “well-regulated militia” clause refers to slave patrols, not protection from government overreach. Legal architecture since has limited and outright prohibited Black Americans from owning firearms by perpetuating the narrative that they are a threat.

“The evidence shows that the amendment is based on a foundational fear of Black people,” Anderson says. “We need to document this ongoing fear of Blackness in American society if we are going to have a full discussion about the Second Amendment today.”

Anderson’s argument has drawn attention and critique in national media since it was released June 1. She hopes the conversation will carry into her classroom this fall, when she is teaching about the Civil Rights Movement.

Students already have long played a role in Anderson’s research, and she acknowledges the Emory students and alumni who helped with “The Second.”

Among those who worked as research assistants, helping to find and organize historical records as well as talk through the findings with Anderson, are Ayriel Coleman, a rising senior majoring in history, and Timothy Rainey II, who earned his PhD this spring and is now an assistant professor of religion at St. Olaf College in Minnesota.

“The anti-Blackness I’m describing in this book is to make legible what our students know from casual conversation, and I hope to get a sense from coursework what more conversations they may want to have,” Anderson says.

Those not enrolled in Anderson’s course also may join the conversation when she speaks at the Decatur Book Festival in October.

Reshaping current conversations through history

The book marks Anderson’s latest effort to reshape current conversations through a more thorough examination of history. She won the 2016 National Book Critics Circle Award for “White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide,” her groundbreaking examination of white Americans’ efforts to marginalize and oppress African Americans since the Civil War.

In 2018, she published something of a sequel to that book with “One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy,” which outlines the history of voter suppression to the current era. Anderson also was awarded a 2018 Guggenheim Fellowship for her work.

“I would argue we have an amendment put into place the same way the three-fifths clause was, to debase the humanity of African Americans,” Anderson says, referring to the section declaring that enslaved people should be tallied as less than full people when counting for congressional representation.

“We are not having a full discussion of our history if we do not consider the erasure of Black American history,” she adds.