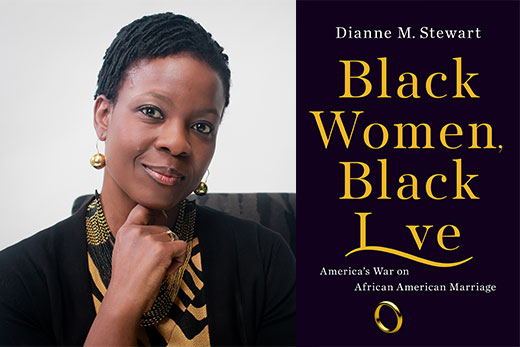

Emory’s Dianne M. Stewart traces the path culminating in her latest book “Black Women, Black Love: America’s War on African American Marriage” to her years of teaching, research, conversations and encouragement from the university community.

“I taught my first course on ‘Black Love’ in 2004 — a relatively long time ago,” Stewart recalls. At the time, she never imagined that her teaching and research would evolve into an in-depth and wide-ranging look at the history, economics, social science and theology of “forbidden Black love,” which she calls our nation’s most neglected civil rights issue.

Stewart, associate professor of religion and African American studies, says she tends “to be very comprehensive” in her research and teaching, but she wasn’t thinking about romantic love as a part of her first course, a seminar, on Black Love.

Then her teaching assistant suggested it, and she began considering her own interest in resilience and women’s joy in the face of oppression, along with her conversations with friends about these issues, and “I knew I had to include it,” she says.

Black romantic love and marriage was the last section of Stewart’s course, but as she began reviewing materials, she became acutely aware of the breadth and depth of scholarly literature, from the impact of slavery on the Black family to the recurring theme “that Black romantic love is deeply entangled with structural power.”

In the book’s introduction, Stewart recalls how, by the end of that first Black Love course, “I could only characterize Black women’s lack of options for meaningful love and partnership with Black men as the nation’s most hidden and thus neglected civil rights issue to date.”

She uses the phrase “forbidden Black love” to refer to “the manifold structures and systems that make prosocial romantic love, coupling and marriage difficult, delayed or impossible for millions of Black people in America.”

Her book is a journey that begins with enslaved women and men arriving in America, and chronicles the many obstacles and often tragic results of four centuries of Black oppression. The book can be a hard read emotionally, and Stewart says some parts were hard to write: Her research ranges from the breaking of family bonds during enslavement, to the terror following Reconstruction, to the adverse effects of federal and state welfare programs, and repercussions of mass incarceration.

Asking questions from a new perspective

Stewart notes the arrival of Carol Anderson at Emory in 2009 as a catalyst for her thinking about the issue. Anderson is Charles Howard Candler Professor of African American Studies and chair of the department. “When Carol got to Emory, we would have these conversations from time to time, and I said, ‘You know, I have been thinking about writing an article.’”

Yet, for all her teaching and research on Black Love, Stewart admits, “I didn’t see a book out there.” She did think again about writing an article on her ideas, “but I never did it; I was too busy,” she says. Her days were filled with coursework and teaching, other research and writing, and serving as an advisor and mentor to PhD students.

“I saw what sociologists were doing, and they are very careful to work within socio-economic parameters when they’re discussing causality, and certainly we know the history of the dire impact of slavery on Black people over centuries,” says Stewart. “But I realized that no one was really putting both of these conversations together — what historians have taught us and what social scientists have discovered.”

More specifically, no one was asking those questions through the lens of love and marriage from the perspective of Black women, she says.

But even then, Stewart says she postponed the project, and she wasn’t able to fit the course on “Black Love” into her teaching plans.

Then came the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012. And everything changed.

Students were angry, enraged, says Stewart. “They were getting involved in different kinds of activist campaigns. They were demanding change on every campus. But what they were often expressing to me and other Black women colleagues, and men as well, was their exasperation, their disappointment, their lack of spiritual resources and resolve to cope.

“And I realized that this was a time when we needed another Black Love course.”

Stewart was encouraged, again by Anderson, to offer the class as a lecture course. “We started off with an enrollment limit of 50, but it didn’t stop until 85 students and five auditors had registered,” she notes.

Spreading beyond the classroom

In the fall of 2016, Stewart teamed with colleague Donna Troka, now senior associate director of Emory’s Center for Faculty Development and Excellence, to offer a one-credit “sidecar course,” open to students in Stewart’s “Black Love” course and Troka’s “Resisting Racism” course. The sidecar, titled “The Power of Black Self Love,” was designed to give students an opportunity to explore the topic through public scholarship.

The course rippled out beyond the classroom: Some of the students’ projects were covered by national media, and one student’s project went viral on social media and was covered by Teen Vogue.

Stewart realized the time had come to take her idea to a wider audience. “I talked with Carol quite a bit about it, and she assured me that my idea was original, that no one has looked at the original sources through this lens,” says Stewart. “I wanted to examine this material through Black women’s hearts, through Black women’s affections, through Black women’s desires for healthy partnership and for marriage.”

In the book’s acknowledgements, Stewart says she was aware that “receiving feedback and suggestions from historians and social scientists was not negotiable,” but that she “never imagined how necessary the expertise of colleagues and friends would be for presenting a nuanced and complicated interpretation of historical events and statistical data.”

Her “thank you” list to the Emory community is detailed and comprehensive, including colleagues in African American studies and religion; her undergraduates, graduate students and research assistants; dedicated staff members; the Bill and Carol Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry; and the Center for Faculty Development and Excellence.

Putting Black love on the civil rights agenda

Despite all the hard truths Stewart brings to light in “Black Women, Black Love,” she doesn't end there. The book explores ways that everyone from public servants and religious communities to the general public can join Black women and men in efforts to undo the legacy of forbidden Black love.

“Black Women, Black Love” outlines proposals for developing the kind of world in which Black love is nurtured and supported, from creating pathways to financial stability and wealth building, to strengthening the range of kinship networks beyond the nuclear family and combatting deeply internalized bias against dark skin.

Stewart points out that overcoming the historical, economic, sociological and psychological barriers to Black love in America isn’t an easy road. “People — especially because of how this subject is treated as a personal hardship — want to approach it through self-help resources.”

And while she endorses the self-help approach, Stewart also wants to start a conversation about where we go as a society, how we imagine the future.

“Look at everything we’ve learned,” she says. “How do we then take this knowledge into our own relationships and our teaching of younger boys and girls, so that we can create a society of people who are ready for love and marriage if they choose?”

“What if we do put Black love and marriage on our civil rights agendas?” Stewart asks. “What if we begin to treat this as an issue that we should take up as activists? That’s the only way to get beyond this impasse, to dismantle these systemic barriers.”