Measuring blood antibody levels against SARS-CoV-2 may distinguish children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), which appears to be a serious but rare complication of viral infection, say researchers at Emory University School of Medicine and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

Children with MIS-C had significantly higher levels of antiviral antibodies – more than 10 times higher -- compared to children with milder symptoms of COVID-19, the research team found.

The results, published in the journal Pediatrics, could help doctors establish the diagnosis of MIS-C and figure out which children are likely to need extra anti-inflammatory treatments. Children with MIS-C often develop cardiac problems and low blood pressure requiring intensive care.

The high antibody levels may represent an exaggerated immune response or a delayed complication of COVID-19 – or a combination of both, according to Christina Rostad, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine and an infectious disease specialist at Children’s. Senior author Preeti Jaggi, MD, is associate professor of pediatrics (infectious disease) at Emory University School of Medicine and Children’s.

“One of the challenges in interpreting these findings in children with MIS-C is that we do not know when they were actually infected with the virus,” Jaggi says. “The rapid emergence of MIS-C has required both physicians at Children’s and researchers at Emory to work collaboratively to quickly understand the clinical course of the disease, treatments, and pathophysiology and has required a huge team effort from clinicians and basic scientists.”

Since the writing of this manuscript, Children’s physicians have continued to see cases of COVID-19, and more than 50 cases of MIS-C have met the definition of MIS-C requiring hospitalization in the Children’s Healthcare system.

“These cases underscore the importance of all the efforts we are taking as a community to decrease transmission of this virus. By wearing a mask, washing your hands, and avoiding large gatherings, you may be saving someone’s life,” Rostad says.

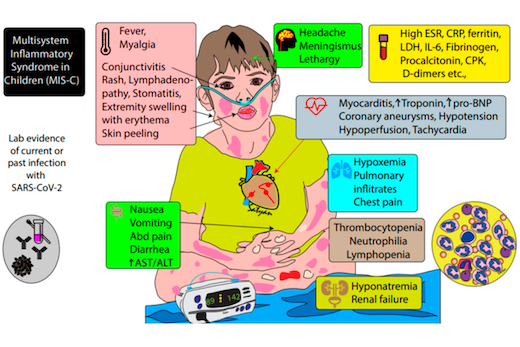

Patients with MIS-C usually present with persistent fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, skin rashes, and severe cases have low blood pressure and shock, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

How MIS-C develops remains mysterious. Recent reports have suggested that it arrives in a second wave of inflammation, after initial viral infection. None of the children with MIS-C studied by the Emory and Children’s researchers recalled having a previous fever or respiratory illness, even though they had high levels of antiviral antibodies. However, the majority tested negative for an active infection (by RT-PCR) at the point of their hospitalization.

The authors remark that it “seems paradoxical” that children without preceding symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection develop such robust immune responses. It may hint that although some children with active infections lack symptoms, they are still capable of developing robust and aberrant immune responses associated with MIS-C.

“These studies provide supportive evidence that MIS-C represents an aberrant immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children,” Rostad says. “However, the mechanisms of this disease process and the reasons why some children develop symptoms while others don’t, remain areas of active research.”

When they first came to the hospital, children with MIS-C mainly displayed gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms. Several of them developed myocardial dysfunction with decreased ejection fraction, which is a measure of the heart’s ability to pump blood. All patients with MIS-C needed to be hospitalized in intensive care because of low blood pressure.

Between March and May 2020, the researchers studied 10 children hospitalized with MIS-C, 10 with symptomatic COVID-19, five with Kawasaki disease and four hospitalized controls. Kawasaki disease is a pediatric inflammatory disease affecting blood vessels, including the coronary arteries, which shares some features with MIS-C. The average age of the children with MIS-C was 8.5 years.

The time elapsed between symptom onset and the time antibody samples were taken varied, generally between 0 and 20 days, with a few in the MIS-C group later than 20 days. The researchers used tests for antibodies against the receptor binding-domain of the viral spike protein and the viral nucleocapsid protein using assays developed in the laboratory of co-author Jens Wrammert, PhD. They also performed live-virus neutralization assays in the laboratory of co-author Mehul Suthar, PhD.

All the children with MIS-C were treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (a mixture of donated antibodies) and half received corticosteroids, a common anti-inflammatory medication. Some of the COVID-19 group were treated with antiviral or immunomodulatory drugs such as remdesivir (4 children) and convalescent plasma (2). All the children with MIS-C eventually returned home. Two of the patients with symptomatic COVID-19 were being treated for leukemia and died due to their underlying disease processes.

The research was supported by the Center for Childhood Immunizations and Vaccines at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, the Georgia Research Alliance, a Synergy Award from Emory University School of Medicine, and a Fast Grant from Emergent Ventures at the Mercatus Center of George Mason University.