Emory University researchers have shown a new HIV vaccine is both better at preventing infection and lasts longer, shielding subjects even a year after vaccination.

Researchers from the Emory Consortium for Innovative AIDS Research in Nonhuman Primates collaborated with their counterparts in the U.S. and Canada on the study. The findings, recently published online in Nature Medicine, provide important insights for HIV prevention, and could have implications for vaccine development in COVID-19 and other infectious diseases.

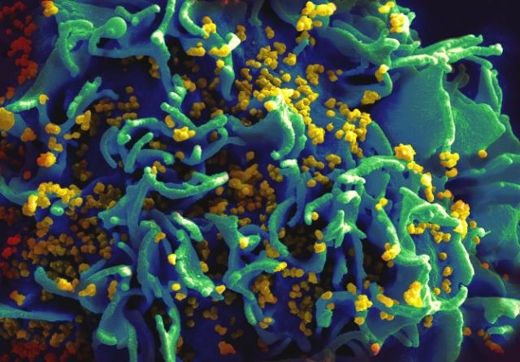

The vaccine, which was given to monkeys, appears to improve protection from HIV infection largely because it targets an area of the immune system that is ignored by most current vaccines.

”Most efforts to develop an HIV vaccine focus on activating the immune system to make antibodies that can inactivate the virus – so-called neutralizing antibodies,” says Eric Hunter, PhD, who is affiliated to multiple Emory organizations including the Emory Vaccine Center and Yerkes National Primate Research Center. “We designed our vaccine to also generate a strong cellular immune response that homed in on mucosal tissues so these two arms of the immune system could collaborate to give better protection.”

Some 38 million people worldwide live with AIDS. While antiviral medications limit the impact of the disease on daily life, HIV continues to infect 1.7 million people annually and cause some 770,000 deaths each year, which makes the Emory team’s work a high priority.

Hunter shares senior authorship with two other Emory colleagues, Rama Amara, PhD, and Cynthia Derdeyn, PhD. In addition, researchers from Stanford University and the University of Minnesota are also senior authors.

To test the vaccine, researchers worked with three groups of rhesus macaques at Yerkes over several weeks. “Nonhuman primates remain the very best model for testing the potential of novel vaccines,” says Hunter.

One group received several doses of Env, a viral protein that stimulates antibody production; the second group received the same series, plus injections of three different viruses that were mildly infectious. Each virus was modified to contain a gene for a viral protein called Gag, which stimulates cellular immunity; and the third group served as the "control" group.

Researchers found the majority of vaccinated monkeys experienced significant initial protection after they were exposed for a period of time to the simian version of HIV. Five months later, the researchers exposed six monkeys from each vaccine group to the virus again. This time, a clear difference emerged: Of the six animals that received the vaccine designed to stimulate both antibody and cellular immunity, four remained uninfected. That was true of only one animal given the vaccine targeting antibody immunity alone.

Interestingly, the animals that received the Env and Gag proteins remained uninfected even though they lacked robust levels of neutralizing antibodies. “This is an intriguing result because increasing the potency of neutralizing antibodies has been thought to be crucial to a vaccine’s effectiveness, but doing so is difficult,” says Derdeyn.

Apart from strengthening immunity, researchers found the Env+Gag vaccine protected animals for a considerably longer period of time, even a year.

Amara says the findings are encouraging and that it brings researchers one step closer to preventing HIV with a vaccine. The team will use the results to refine the way they approach vaccine development. This will include investigating ways to improve cellular and neutralizing antibody responses for greater HIV protection before moving into clinical trials.

“We think the same approach could be feasible for other pathogens, including influenza, TB, malaria and, now, COVID-19,” Amara says.

The study was supported at Emory with funding from the National Institutes of Health, Emory’s Center for AIDS Research, and the Yerkes National Primate Center.

The Emory Consortium for Innovative AIDS Research in Nonhuman Primates (CIAR-NHP) seeks to develop new strategies for preventing and curing HIV/AIDS. The research partnership brings together an interdisciplinary mix of highly collaborative investigators focused on a wide range of HIV vaccine and cure research, with the aim of developing a potent HIV vaccine that produces a broad and sustained immune response.