Alessandro Veneziani loves numbers and he loves people. A professor in Emory’s Department of Mathematics and Department of Computer Science, he uses numerical analysis and computing for real-world applications — such as modeling blood flow through the vascular system to determine risks for an aneurysm or a stroke.

The pandemic shifted the focus of Veneziani — a native of Italy, one of the hardest hit countries — onto the rising number of new COVID-19 cases and the people affected by them. After the campus closed, Veneziani and colleagues launched an Emory student contest to create mathematical models that might yield useful data for controlling the pandemic. More than 90 students jumped in to form teams and take on the challenge.

“The students want to help, and this is a way they can use what they’re learning,” Veneziani says. “They are part of the Emory community and when you work as a community you have more power to make bigger contributions to the world.”

On February 19, only two cases had been detected in Italy, and COVID-19 still seemed a distant problem in the country. On that day, about 45,000 soccer fans from the region of Veneziani’s hometown, Bergamo, traveled to Milan to watch their elite team, Atalanta, beat the Spanish challenger in a Champions League match. They returned home to celebrate.

On February 20, in his adopted hometown of Atlanta, Veneziani celebrated the birth of a daughter, Eleonora, with his wife, Manuela Manetta. Manetta is also Italian, from Abruzzo near Rome, and is a lecturer in Emory’s Department of Mathematics.

By March 19, Italy had become the country with the highest number of COVID-19 deaths in the world. And ground zero was Bergamo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Members of Veneziani’s family still live in the town. They are quarantined in separate homes where he stays in touch with them through Skype. His brother takes his mother meals and leaves them outside her door. “I’m mostly worried about my mom,” Veneziani says, “because she’s 78 and the most vulnerable.”

Veneziani felt frustrated being so far away as Bergamo struggled. “I was awake late at night, my wife was feeding our baby, and I was thinking and thinking,” he recalls. That’s when he got the idea for the math modeling contest.

“The spirit of the initiative is that it is less a competition than a collaboration,” Veneziani says. “We are coming together to fight a common enemy, a virus. And our weapons are differential equations.”

Jim Nagy, chair of the Department of Mathematics, supported the idea and three faculty immediately volunteered to help manage the initiative: Manetta, Longmei Shu, a visiting faculty member, and Maja Taskovic, an assistant professor. They are pulling together other faculty from related disciplines across campus to select the top three student groups in May. Veneziani also enlisted entrepreneur Russell Medford as a judge. A former physician at Emory, Medford is now chair of the board of the Center for Global Health Innovation in Atlanta and is always on the lookout for a fresh perspective.

Students from all majors were welcomed into the initiative, from first years on up.

Veneziani tells stories of hope and resilience from Bergamo to inspire the students, who are all dealing with their own concerns surrounding the pandemic. Bergarmo is situated on a hill and surrounded by stone fortress walls dating to 1500. “Bergarmo is very beautiful and very old,” Veneziani says. “Its people are tough. And they are also generous.”

Bergarmo is known for skilled builders from a range of construction trades. As the existing medical facilities reached peak capacity, people from the region adopted the slogan “Bergarmo, don’t give up” and came together to build a new hospital. “Bergamo was under a storm and people volunteered to help. They built a hospital in just six days,” Veneziani says. “That’s incredible. That’s what a community can do when it comes together.”

Now the pandemic curve is showing signs of flattening in Bergamo and across Italy. On April 11, the United States surpassed Italy as the country with the most deaths from COVID-19.

The Emory student teams are finishing up their projects, including 20-page papers. Students were given free rein to pursue any kind of mathematical modeling project to help understand the spread of the pandemic and make useful predictions.

“The main aim of this initiative is educational,” Veneziani says. “I want students to understand that developing a mathematical model is a creative process. You come up with an idea, introduce some assumptions and then check them with reality to see if you’re on the right track. You have to keep refining your model, keeping it as simple as possible but complex enough to learn something useful.”

“I’ve loved math since I was very young,” says Sanne Glastra, a sophomore majoring in qualitative theories and methods who is involved in the contest. “This is a chance to apply data science to a real problem that everyone is facing right now.”

Her team is modeling COVID-19 through the lens of nursing homes. “I’m learning a lot about how to collect data on health and demographics and work with a team to figure out what’s relevant,” says Glastra, who is quarantining with her family in Boston.

“The students have fresh energy and fresh minds,” Veneziani says. “They may come up with new ideas that deserve further exploration after the competition ends.”

Veneziani also has a math modeling project for COVID-19 underway with one of his former students, Alexander Viguerie, who is now a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Pavia, near Milan. Viguerie, a native of Atlanta, began his academic career at Oxford College before coming to the Emory campus for his undergraduate degree and his PhD in math, which he received in 2018.

Viguerie still has collaborations with Veneziani. He flew into Atlanta on February 20 so the two could work on a project, unrelated to COVID-19, that was expected to last a few weeks. It was the day Veneziani’s daughter was born and the news reported a confirmed COVID-19 case in Italy not related to travel, meaning the virus was on the loose in the country.

“It was surreal, the timing of everything,” Viguerie says.

He and Veneziani soon scrapped their planned collaboration and began to work on modeling COVID-19 transmission. From his parents’ home in Georgia, where he is spending quarantine, Viguerie pulled together an international team for the project. Members include an expert in supercomputing in Germany; an expert in disease modeling from the University of Texas; students from the University of Pavia; and three undergraduates from Emory: Glastra, Kasey Cervantes and Shreya Rana.

“Everyone jumped right in to help,” Viguerie says.

“We’re really pumped about this project,” says Cervantes, a junior majoring in biology and minoring in computer science who is quarantined with his family in Chicago. Cervantes previously worked on a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention project to model malaria transmission and plans a career in computational biology or epidemiology.

Rena is a sophomore, majoring in neuroscience and behavioral biology and minoring in computer informatics. She is quarantined with her family in the San Francisco Bay area. “The more information we have on how a virus spreads through a community, the more prepared we can be in the future,” she says.

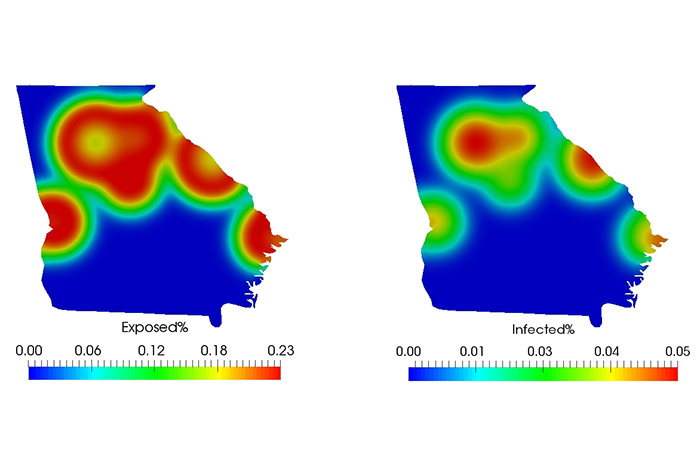

The researchers are modeling the spatial-temporal spread of COVID-19. The team chose the state of Georgia as the framework for their model, which they hope could eventually be applied elsewhere.

Health data is collected at the county level, Viguerie explains. Georgia happens to have a high number of counties that are relatively small compared to other states, or to Italian provinces, which yields a greater level of spatial precision for the modelers.

“This is a long-term project, not intended for decision-making today,” Viguerie stresses. “We want to create a tool for down the road. We might learn something useful, for instance, that could help in the case of later waves of the outbreak.”

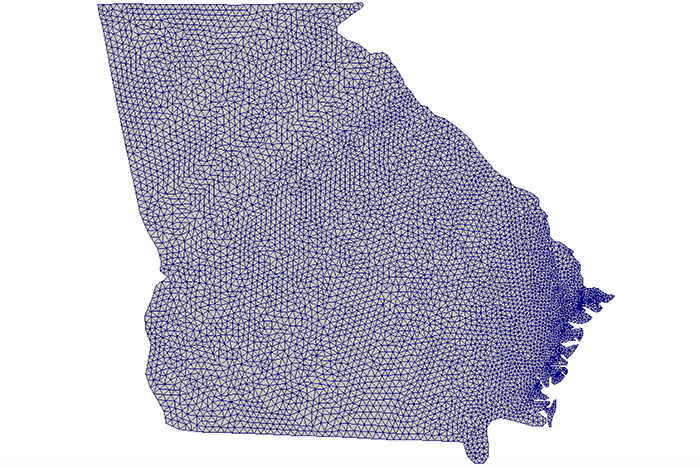

The researchers created a digital map of Georgia and broke it into a mosaic of 100,000 individual points in space. They wrote differential equations for variables related to COVID-19 transmission and created a computer program including all the equations. They are now running preliminary simulations to test various scenarios and see if the model works.

“You start with a simple model and progressively make it more and more complex,” Viguerie explains. “Our model seeks to describe the spread of COVID-19 across time and space. And from there, we can hopefully use the model to learn some mechanistic natures of the spread.”

By comparing the data on symptomatic spread to actual new cases, they can make assumptions to test. “Certain things, like asymptomatic cases, are difficult to measure but possible to simulate using a model,” Viguerie says. “Good models and simulations are crucial with a disease like COVID-19.”

For Veneziani, who officially became a U.S. citizen in February, the Emory student competition and the international project with his former student are both “emergency” measures and business as usual. He has long used math to tackle healthcare problems and to forge bonds between people and countries.

Emory has many specialists working on various aspects of COVID-19, from nurses and medical doctors to researchers specialized in biology, chemistry, epidemiology, virology, infectious diseases and vaccine development, as well as experts in social, historical, cultural, mental well-being, legal and ethical aspects of disease.

“Math is a common language that joins all these forces so we can all communicate,” Veneziani says. “The enormous problem of this pandemic is truly interdisciplinary. Emory is working together, and the whole world needs to come together. We will fight this virus together and we will win. Like in Bergarmo, at Emory we don’t give up.”