Justin A. Joyce isn’t a fan of Westerns.

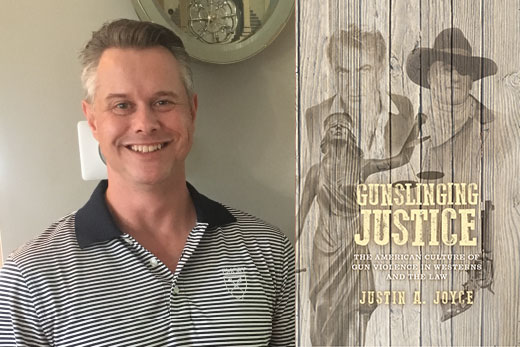

That might seem at odds with Joyce’s newly released first book, “Gunslinging Justice: The American Culture of Gun Violence in Westerns and the Law.”

Joyce — managing editor of the James Baldwin Review and research associate to Emory Provost and Executive Vice President of Academic Affairs Dwight A. McBride — has a long history of exploring the intersections of culture and law.

“Gunslinging Justice” explores the evolution of America’s longest-enduring popular genre and the legal philosophies surrounding self-defense and gun rights, presenting a new take on an old genre by reading Westerns alongside the historical development of the American legal system.

Joyce’s work as an African Americanist studying critical race theory, queer theory and discursive communities helped to sharpen the focus of his research, informing his book’s exploration of representations of Anglo American masculinity in U.S. legal and cultural realms.

“I have been very involved and interested, throughout my undergraduate and graduate studies, in gender and race and representation around those,” says Joyce, who based his master’s thesis at the University of Chicago on two films that were released as he began his graduate studies, “Fight Club” (1999) and “American Psycho” (2000).

“These two films are part of a larger culture of aggressive articulation of masculinity. In thinking about how that was portrayed, the Western genre came up again and again,” he says. “You can’t really talk about representations of late 20th-century films without talking about what happened before and what this is responding to.”

From “Jesse James” in 1939 to Clint Eastwood’s “Unforgiven” in 1992 and through Quentin Tarantino’s 2012 “Django Unchained,” Joyce explores the historical emergence of the Western as an expression of a “very small period of time in a very small geographic region that has exploded into an important national mythology.

“And during the roughly same historical period, the United States was creating a great deal of legislation and jurisprudence about when and how and who is able to stand their ground and kill other people,” Joyce says.

As American laws and societal norms have evolved, so have modern Westerns, Joyce says.

“The Western as a genre is a rarified thing. It is not popular in the way it used to be, but it still exists and works, in a way, to change the justifications for violence so they are now socially acceptable,” Joyce says. “If you look it as a revenge genre, it is the distinction between whose violence is criminal and whose violence is careful and restrained and deliberate.”

Westerns less ‘anti-law’ then you might think

Scholars have interpreted the Western as either an expression of masculine anxieties over economic and social transformations, or a fantasy of swift, extralegal violence at odds with the procedural complications of American law.

“Gunslinging Justice” argues that when examined alongside changes in justifiable homicide laws and gun rights jurisprudence in the United States, Westerns are less “anti-law” than they appear. While the genre's climactic shootouts may look like a masculine opposition to the codified American legal system, this gun violence is actually enshrined in the development of laws regulating self-defense and gun possession.

Using the example of the 1962 film “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” Joyce contrasts the character of Ransom Stoddard, played with tortured sincerity by James Stewart — a newly minted Eastern lawyer come West to find his fortune — and gruff, blustery Westerner Tom Doniphon, played by quintessential Western actor John Wayne.

After his stagecoach is set upon by the outlaw Liberty Valance and his gang, Stoddard is savagely beaten by Valance for defying him in defense of a fellow passenger. Although battered and bloodied, Stoddard insists he wants to bring Valance to justice and see him jailed for his crimes.

Doniphon scoffs. “Oh. Well, I know those law books mean a lot to you, but not out here. Out here a man settles his own problems,” he says, slapping the butt of his pistol.

The rest of the film is an examination of legal justice versus vigilantism and the long-term results of the characters’ actions.

“Which version of the story is the right one? Which one gets accepted or broadcast is what the film is concerned with,” Joyce says. “Which type of masculinity is the one to which we want to say, ‘Yes. Do our violence for us because you have reason.’ It reveals a lot of anxiety at the time it was made around whether it was still OK to have a racist, sexist hero, or do we need a different sense of justice?”