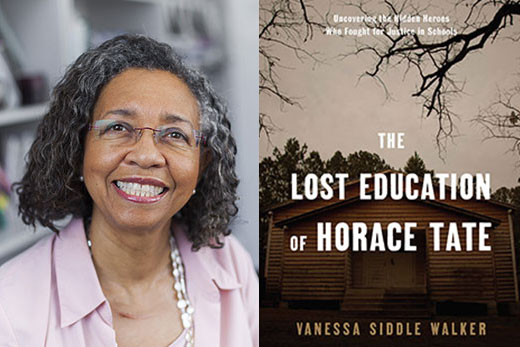

Vanessa Siddle Walker’s new book, “The Lost Education of Horace Tate,” takes the shape of a mystery, fitting for a narrative that features a hidden office, clandestine meetings under the cover of dark and other secrets that add to the history of segregated schooling.

We meet the title character in the introduction, when Tate was an aging retired Georgia state senator. Walker, Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of African American Studies at Emory College, reached out to him on the advice of colleagues familiar with her acclaimed research on the segregated education system.

Tate goes on to talk with Walker for two years about his early role as a teacher and principal, sharing stories of covert travel and meetings with fellow educators, Martin Luther King Jr. and powerful politicians to advance education for black children.

After Tate died in 2002, Walker honored his final wish and discovered a hidden attic in his downtown Atlanta office. The secret space was a trove of archival material that backed up Tate’s tales and revealed the whodunit: teachers’ organizations, not the NAACP, shaped the events that led to, and came after, the Supreme Court’s desegregation ruling in Brown v. Board of Education.

“We didn’t think to consider how Thurgood Marshall knew who would litigate,” Walker says. “An entire hidden network of black educators committed to being certain that black children had the same educational opportunities white children had were central agents in connecting those local advocates with the national NAACP.

“It changes everything to realize how important educators were,” she adds. “They secretly provided the money, the data on inequality and the plaintiffs. Black educational networks were the invisible thread that helped generate the civil rights movement.”

Rethinking how schools desegregated

It is a history that Walker has researched for 25 years. “Their Highest Potential,” her book examining the learning environment in the classroom of a segregated school and its link to the broader community, garnered Walker the prestigious Grawmeyer Award for Education and the American Educational Research Association (AERA) Early Career Award. This spring, she was voted president-elect of the AERA based on her work.

Tate lived that history. A graduate of Fort Valley State College and the first black PhD graduate from the University of Kentucky, he began working in the segregated education system as a high school teacher in 1943.

He later rose to principal and then head of the black educators’ society, the Georgia Teachers and Education Association (GTEA).

Tate’s observations as a student driver for Horace Mann Bond, the president of Fort Valley, taught him how to use opponents’ prejudices and weaknesses to achieve goals. He learned not only how to officially succeed, but also the value in hiding his work to design an ambitious curricula for black students and training program for teachers.

That same savvy led him to squirrel away the records of black schools and the black school system of Georgia. Nearly a dozen filing cabinets and stacks of files were hidden for decades in the former GTEA upper-floor offices, until Tate told Walker about his stash.

“The collection shows how Dr. Tate and black educators created a curriculum that shows America is not living up to its promise of equality,” says Walker, who spent 15 years going through the massive collection to piece together how the hidden network functioned.

“They created a generation of kids who are not mad but have the desire and education to make American better,” she explains. “Dr. Tate’s legacy, and that of other educators who were activists, really forces us to rethink how we desegregated and how we fell when those advocacy networks went away.”