A collaborative research team led by Ann Chahroudi, MD, PhD, of Emory University is recommending long-term clinical monitoring for infants infected with Zika virus early after birth. The recommendation is based on the team’s research results showing for the first time that postnatal Zika virus infection of rhesus macaque infants results in persistent abnormalities in brain structure and function as well as behavior and emotions.

Findings from the study were published Thursday, April 4 in Science Translational Medicine.

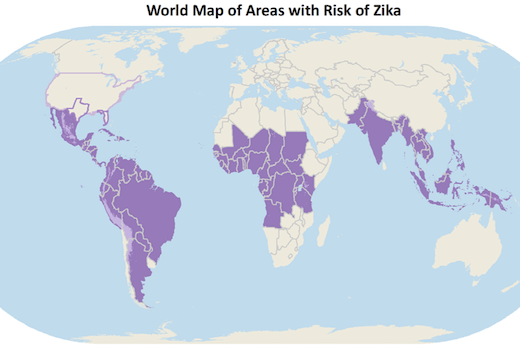

Much of the concern surrounding Zika virus infection focuses on fetuses infected in utero and the potential resulting microcephaly and other anomalies. The study’s authors hypothesized that Zika virus infection during the first year of life, when the brain undergoes major growth and maturation, could also have adverse neurological consequences that may last for months and perhaps years.

Working with eight infant rhesus macaques as part of projects the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory+Children’s Center for Childhood Infections and Vaccines (CCIV), and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta funded, the researchers explored if the outcome of infection with Zika virus early after birth was similar to other viral infections in infancy, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) and HIV. These infections can lead to significant long-term neurologic complications, which is exactly what the researchers found with Zika virus.

“The neurological, behavioral and emotional differences remained months after the virus cleared from the blood of the infants,” says Chahroudi, the study’s lead researcher. “This is why our team now recommends more than just routine monitoring for pediatric patients known to be infected with Zika.” Chahroudi is a faculty member in the Emory School of Medicine (SOM) Department of Pediatrics, an affiliate scientist in the Division of Microbiology and Immunology at Yerkes, and director of the CCIV.

The researchers used structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans at three and six months of age to evaluate the impact of Zika virus infection. “The scans were critical for confirming which brain regions were affected by the virus and/or indirectly harmed by inflammation and, importantly, the persistent brain abnormalities predicted some of the behavioral changes we observed,” says Chahroudi.

“Some of the specific findings we report are Zika virus invasion of the nervous system, enlargement of lateral ventricles, and abnormal maturation of the hippocampus and other brain regions,” adds Maud Mavigner, PhD, an instructor of Pediatrics at SOM and first author of the published paper. “These results are similar to congenital infection, but also provide new insights into changes that occur in the first year of life with early postnatal Zika virus exposure.”

The monkey model could allow researchers to study in more detail the effects of postnatal Zika virus infection on the brain and give them opportunities to test therapies for alleviating or even preventing the neurologic consequences of Zika virus infection. Already the research team has found postnatal Zika virus infection’s effects on the brain are more subtle than congenital infection. In addition, there did not appear to be an effect on vision or visual recognition memory in this pilot study. “This gives us hope that in our future work we can find ways to limit Zika virus’ effect on the developing brain,” says Chahroudi.

The current study was conducted with a grant from the Yerkes Pilot Grant Program (P51 OD011132), which provides one year of seed funding intended to help researchers produce initial scientific results that will generate high-impact preliminary data, positively impact future research studies and result in peer-reviewed, research project grants from outside sources, such as the National Institutes of Health. A five-year evaluation of the Yerkes program showed every $1 the center invests in pilot research programs results in more than $20 in resulting grant funding. In total, this represents almost $40 million in new research grants for the Yerkes Research Center, which is making breakthrough discoveries possible, including this latest Zika virus research, as part of work to help people across generation and the world live longer, healthier lives.

The CCIV and the Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta also provided support.

In addition to Yerkes, Emory and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta researchers, the collaborative research team includes researchers from Howard University, Oregon Health and Science University, University of Miami, University of North Carolina and Wisconsin National Primate Research Center. The team’s next steps are to study the brain and behavior in a larger cohort of animals after early life Zika virus infection and to evaluate outcomes beyond one year of age.

Dedicated to discovering causes, preventions, treatments and cures, Yerkes National Primate Research Center (NPRC), part of Emory University’s Robert W. Woodruff Health Sciences Center, is fighting diseases and improving human health and lives worldwide. The center, one of only seven NPRCs the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funds, is supported by $79.1 million in research funding (all sources, fiscal year 2017). Yerkes researchers are making landmark discoveries in microbiology and immunology; neurologic diseases; neuropharmacology; behavioral, cognitive, and developmental neuroscience; and psychiatric disorders. Since 1984, the center has been fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, regarded as the gold seal of approval for laboratory animal care.