Microbiologists have identified a component of a genetic switch, which they call a potential "Achilles' heel", for a type of bacteria often associated with wounded warriors.

The switch makes it possible for Acinetobacter baumannii to change between a virulent, hardy form and an avirulent form that is better at surviving at lower temperatures outside a host. Defining the switch could map out targets for new antibiotics.

The results were published Monday, April 23 by Nature Microbiology.

Acinetobacter baumannii is sometimes called "Iraqibacter," because of its presence in soft tissue infections experienced by soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. However, it is an important pathogen is hospitals worldwide. In 2017, the World Health Organization named multidrug-resistant A. baumannii as one of its top three threats. Notoriously difficult to fight with disinfectants or detergents as well as antibiotics, A. baumannii is most commonly seen in ventilator-associated pneumonia or central-line-associated blood stream infections.

Phil Rather, PhD, and colleagues from Emory Antibiotic Resistance Center found that A. baumannii bacteria rapidly changed between virulent forms and non-virulent forms. However, a "trick" of keeping the bacteria at a low density can prevent them from switching back and forth, Rather says.

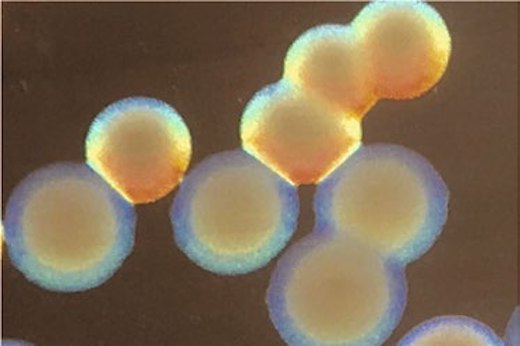

Colonies of the virulent form are opaque, compared with the translucent colonies of the non-virulent form; seen by electron microscopy, the virulent bacteria produce a thicker outer capsule. The opaque form is more resistant to hydrogen peroxide, disinfectants commonly used in hospitals and host defense molecules produced by the immune system.

The researchers discovered that the translucent form of A. baumanii had a regulatory gene called ABUW_1645 turned on, while the opaque form had it turned off. Forcing bacteria to turn this gene on all the time disabled the switch: the bacteria were now stuck in the translucent, avirulent form. They were then more vulnerable to host defense molecules and disinfectants.

"This switch could be an Achilles' heel for Acinetobacter," Rather says. "It could be the key for small molecules that could lock it in the avirulent state."

ABUW_1645 looks like it encodes a DNA-binding protein, similar to another known to respond to the antibiotic tetracycline. It's not known whether ABUW_1645 has a "trigger" (ligand), but more investigation could show whether it is a potential drug target, Rather says.

In hospitalized human patients with A. baumannii infections, the opaque form of the bacteria dominated, but a translucent form could be selected out in culture, which had ABUW_1645 turned on.

The less virulent form of bacteria seems to be better at coalescing into biofilms at room temperature and at importing nutrients from the environment. Warmer temperatures found in a host turn off ABUW_1645 and activated switching to the virulent form.

"We plan to investigate this switch in more samples from human infections," Rather says.

In the paper, the authors note that human infections seem to select for cells that are best-suited for hospital persistence. This may account for the growing difficulty eradicating the bacteria as well as high virulence. Acinetobacter baumannii has been considered "nosocomial," meaning acquired in a healthcare setting. But community-acquired infections have been rising, they write.

Collaborating with the lab of David Weiss, PhD, the researchers showed that the virulence-disabled bacteria could be used as a live attenuated vaccine in mice, protecting them against later infection by the virulent form.

There are other components to the virulence switch, Rather says. Disabling ABUW_1645, as opposed to putting it in overdrive, does not impair the ability of the bacteria to switch forms.

"That's our next step - to go upstream," he says. "We are now studying other mutants that affect the switch."

Postdoctoral fellows Chui Yoke Chin, PhD and Kyle Tipton, PhD are co-first authors of the paper. Eileen Burd, PhD, director of the clinical microbiology lab at Emory University Hospital, is a co-author.

The research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R21AI115183, R01AI072219, R21AI098800), a Veterans Administration Merit Award (I01BX001725), the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the Georgia Clinical and Translational Science Alliance (UL1TR000454).