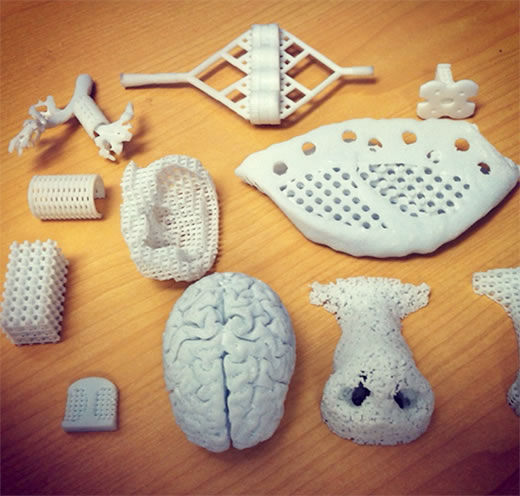

As part of the DIY revolution, Emory doctors are using 3D printers to make body parts, medical tools, training models, and prototypes.

At the Emory Orthopaedics & Spine Center, sports medicine surgeons like Mathew Pombo are using 3D printers to design custom knee replacements for elite athletes during their careers and after retirement.

“In aging athletes, you can see the impact of a lifetime of sports and activity,” says Pombo, who has performed about 500 customized 3D-knee replacements at Emory Johns Creek Hospital. “The patient-specific 3D-knee implant is ideal for those with arthritic knees who are considering surgery.”

Making patients’ lives easier at home is the aim of Steve Goudy, director of the Division of Pediatric Otolaryngology at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and associate professor at Emory’s School of Medicine, who is using 3D printers to create medical devices that patients can take home with them. One of his current projects is a collaboration between Emory, Georgia Tech, and the Global Center

Tissues and cells are the inks that Michael Davis, associate professor of cardiology and biomedical engineering and director of the Children’s Heart Research and Outcomes (HeRO) Center, is using in his lab.

“We are printing patient-specific heart valves and heart patches for pediatric patients,” he says. “Children are often treated using repurposed adult medicines or other, less effective treatment methods.”

Transplanted donor valves have drawbacks, sometimes requiring antirejection medications and subsequent surgeries to replace the initial valve since it does not grow as the child ages. Davis and his team are developing child-sized valves using the patient’s own cells through Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells technology. “We want to fix the patient, using the patient, within the patient,” says Davis.

Stitches and staples are effective at closing wounds, but they can also be invasive and painful and leave visible scars. Felmont Eaves, professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery at Emory and director of the Emory Aesthetic Center, has spent six years using 3D printing to transform the way surface lesions and wounds are treated.

“We created a very dynamic and flexible device that will pull a wound together and relieve its tension,” he says. “3D printing allowed us to cost-effectively make hundreds of models and prototypes to perfect the dimensions, shape, and thickness of our device design.”

Doctors were at a loss for ways to treat a baby with a windpipe so weak it often collapsed, so they approached biomedical engineer Scott Hollister, who used 3D printing to craft a custom, infant-sized tracheal splint to open the baby’s windpipe. Hollister, the Patsy and Alan Dorris Chair in Pediatric Technology at the Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Emory and Georgia Tech, is now setting up the Center for 3D Medical Fabrication. “We want to support clinicians’ ideas by providing them with the capability to design and 3D-print patient-specific devices,” he says. “This new center makes it clear that the development of groundbreaking 3D-printed creations by Emory innovators will continue to grow, evolve, and proliferate.”