Pitts Theology Library at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology holds the largest collection of works by German theologian and Protestant Reformation founder Martin Luther in all of North America. The acclaimed collection included one example of Luther’s handwriting, a manuscript note from late in Luther’s life.

Until now.

Thanks to Pitts Library’s digital archives, a second documented example of Luther’s handwriting has been spotted by a scholar from across an ocean. Ulrich Bubenheimer, a retired professor from Georg-August-Universität in Göttingen, Germany, and a leading expert on Luther, discovered this new example of Luther’s handwriting while working with a printed bibliography in Pitts Library’s Richard C. Kessler Reformation Collection.

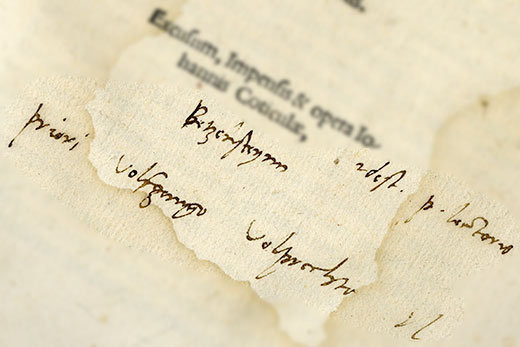

The three-line inscription appears on the title page of a 1520 pamphlet, author previously unknown. Bubenheimer’s discovery also helped identify the author of the pamphlet, which until now had been a subject of debate among scholars.

“Our immediate reaction was excitement,” says Bo Adams, interim director of the Pitts Library. “We immediately wanted to verify the claim with advisers of the Kessler Collection, which we did.”

Bubenheimer was working with the print bibliography, which includes images of the title pages of many Kessler works. He saw the inscription and suspected he was looking at Luther’s handwriting. He immediately emailed the library.

“With the ease of digitization and dissemination, we were able to send Professor Bubenheimer higher resolution images, which he was then able to use to confirm his initial assessment,” says Adams.

“I would like to inform you that the hand-written inscriptions on the title page are a previously unknown Luther autograph and that all three lines are written in Luther’s own hand,” Bubenheimer wrote.

Bubenheimer translated and provided context for the three lines of the Latin inscription. The key line of the inscription is Luther’s explanation of who is the author of the work. The work itself is a mocking dialogue about the Pope’s decision to excommunicate Luther and was published under a pseudonym. In the inscription, Luther is writing to a fellow Augustinian prior, identifying the author as a companion of his.

“As my colleague Armin Siedlecki [head of cataloguing for the library] likes to say, Luther basically says ‘Hey, this is written by one of us!’” says Adams.

“With the identification of the inscriber, your library has been enriched by a Luther autograph,” wrote Bubenheimer.

Broad access to rare documents

With Pitts Theology Library no longer limited to issuing print versions of these rare 16th century documents, online access allows anyone with expertise like Bubenheimer to help unearth new findings, says Adams.

“We are excited about drawing upon scholarly expertise around the world to help us better describe the holdings of this incredible collection,” says Adams. “This particular episode provides further impetus for us to increase our digitization efforts so that the treasures of the Kessler Reformation Collection can be available to researchers, teachers and students around the world.”

And a treasure it is. In his recent book marking the centennial of the Candler School of Theology, university historian Gary Hauk notes, “The Kessler Collection ranks among the most impressive resources for Reformation Studies in the United States and has no parallels in the South.”

On Oct. 31, 1517, Luther published his Ninety-five Theses, a series of statements about the power of indulgences and the nature of repentance, forgiveness and salvation, generally seen as the beginning of the Protestant Reformation.

Pitts Library’s current exhibit, titled “From Wittenberg to Atlanta,” marks the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation and the Kessler Collection's 30th anniversary.

It includes Luther's final authorized edition of the Ninety-five Theses in book form with his own commentaries, as well as the first printing of Luther’s translation of the New Testament from the original Greek into German, printings of the 1530 Augsburg Confession, the first published edition of Erasmus’s Greek New Testament, a 15th-century Book of Hours, and illuminated medieval manuscript leaves.

The exhibit runs through Nov. 27. and chronicles how these incredible print treasures came to Atlanta in physical form.

“This episode reminds us of our responsibility to spread access to these documents digitally around the world,” says Adams.