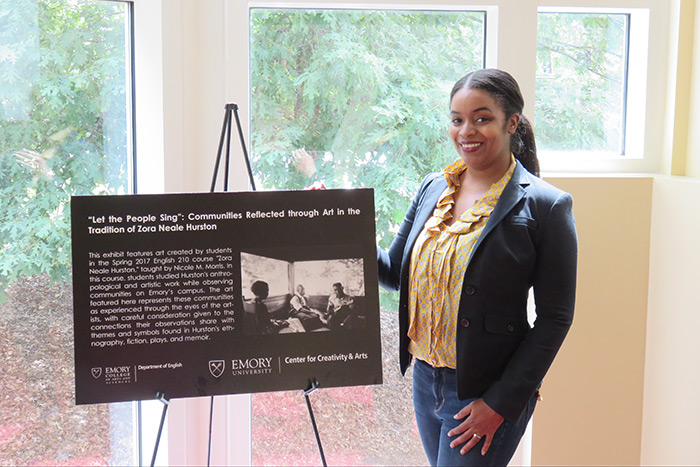

“‘Let the People Sing’: Communities Reflected Through Art in the Tradition of Zora Neale Hurston,” an exhibition created by Emory students as a class project, is on display in the Schwartz Center for Performing Arts’ Stipe Gallery through Sept. 1.

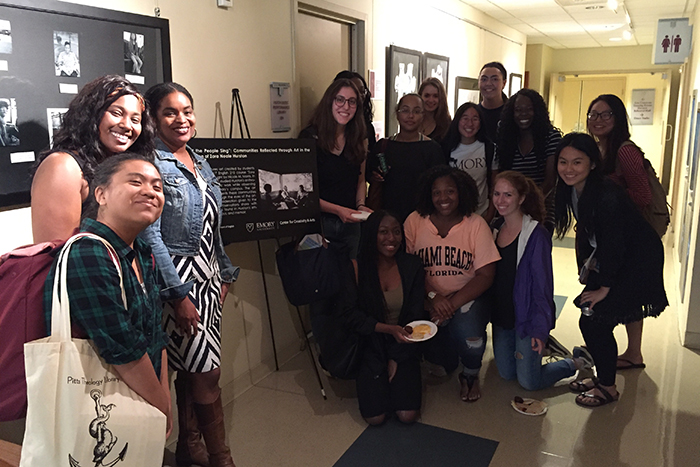

Emory College students created the artwork in a spring semester English 210 class on the renowned American folklorist and writer. Hurston’s art, which celebrated the African American culture of the rural South, is associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Her best-known work, “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” is regarded as a seminal work in both African American literature and women's literature.

"Hurston’s work provided the perfect blueprint for our project because of the ways that her work marries community observation and art that spans genres," explains Nicole Morris, the instructor for the class and a PhD student in the Department of English. "She also placed primacy on highlighting communities that often went under- or misrepresented in larger American culture.

"Following in Hurston’s tradition, my students chose to create artwork based on their observations of communities that they felt were under-examined, misunderstood or in ways invisible on Emory’s campus," Morris says.

For the project, students engaged with or observed the Emory Police Department, patrons at Kaldi’s Coffee, commuters on the Cliff Shuttles, the African Students’ Association and employees in Campus Services.

Emory Report caught up with Morris to learn more about the project and how it was created.

What goals do you hope this exhibit accomplishes for viewers?

A major focus for Hurston was to allow space for the voices of folks from all walks of life. I hope this exhibition provides visibility and complicates perceptions and representations of the communities explored in the artwork. It would be amazing if this exhibit opened ongoing dialogue between students and other communities at Emory.

What do you hope students learned from creating this exhibit?

Rather than simply reading and discussing Hurston’s work, we interrogated her techniques and the relationship between her anthropological fieldwork and her art, and then participated in a mini version of this process. I hoped that this non-traditional approach would prompt new questions about Hurston’s texts, and take reading-based discussions in new, exciting directions. I’m a huge fan of engaged learning, as I feel that it moves students beyond the standard understandings of authors and texts.

I wanted students to more fully understand Hurston’s experiences — as an observer, and as an artist — by engaging in similar processes. My students had to represent communities through art and were faced with several difficult decisions and considerations as a result. Based on their thoughtful products and insightful contributions to class conversation, I would say that my goals as an instructor were exceeded.

Were the materials easy to find and readily available?

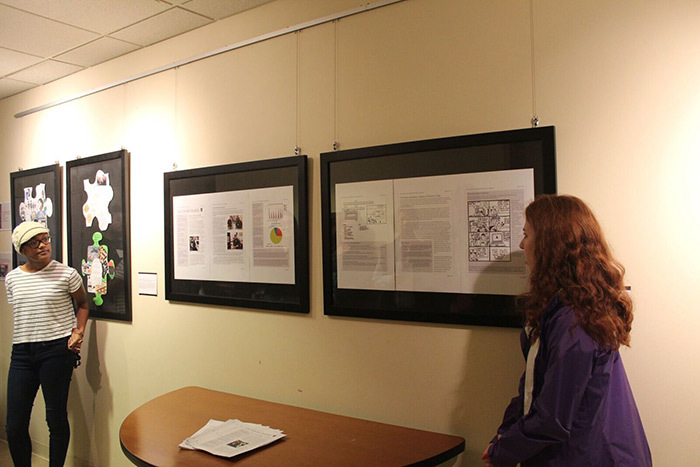

Emory Center for Creativity & Arts was very supportive of our project. Candy Tate, assistant director, granted my students access to the arts cottage, and students could use any materials available there.

Did you learn something unexpected or new by leading this project?

I was thrilled to learn that spaces are reserved on Emory’s campus specifically for student artwork. Also, I was surprised by the willingness of communities such as the Emory Police Department to embrace our project. They were incredibly open to my students, even inviting them to ride along during their shifts. Through the work my students performed, I learned a tremendous amount about the communities they observed.

What else did the project produce?

Working closely with Megan Slemons in the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship, we were able to create a “Map of Hurston’s Places.” This assignment was entirely optional so it was wonderful to see so many students contribute with thoughtfully chosen photographs and explanations connecting the location to Hurston’s work and life.

Was it difficult to get the exhibition installed?

No, it was incredibly easy. Dr. Tate was the only person I had to reach out to. She expressed immediate excitement about our project, and the rest unfolded smoothly. Projects such as the one my students completed, incorporating the arts into their studies in non-traditional ways, are precisely the types of projects that the Center for Creativity & Arts is looking to support, she said.

The Stipe Gallery is located just outside the Arts Commons on the first floor of the building, accessible from the Goizueta Business School Courtyard.