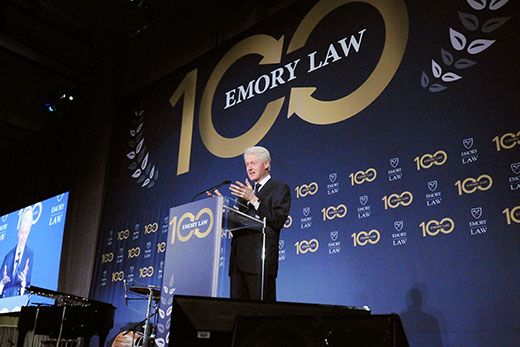

When you turn 100, you might be expected to look backward more than forward. Not so for the Emory University School of Law on the occasion of its 100th anniversary, which was marked with a formal celebration April 29 featuring former U.S. President Bill Clinton and former U.S. senator and Emory Law alumnus Sam Nunn.

The Emory Law Centennial Gala, which drew a crowd of 1,200 to a transformed Woodruff PE Center, was the culmination of a weekend of reunion and Centennial-themed events, and the final event in a series of nationwide events celebrating Emory Law’s founding in 1916.

And while the event commemorated milestones in the law school's history, its focus was on the future, and the key role that both Emory Law and the rule of law more generally can play in solving disagreements and healing divisions.

“We still live in the most interdependent age in human history. Interdependence is a force for good and bad," Clinton said in his keynote address. "If you believe in the rule of law, you must find a way to build up the positive and reduce the negative forces of our interdependence.”

Expanding the ‘Us’

As the gala began Saturday night, the first person at the podium was a recently accepted student, Sean Ripoll Cruz 20L, who radiated enthusiasm for his new academic home. Though fresh on the scene, he already embraces Emory Law's tradition of excellence and competitive spirit. “If anyone wants to share any class notes, I am at table five," Cruz joked.

Underlining the feeling of family and community that characterized the evening, Cruz had the honor of introducing his mother, an artist retired from the Metropolitan Opera, Aixa Cruz-Falu, who beautifully rendered the National Anthem.

The night’s themes, threaded through all the speakers’ remarks, were Emory Law’s tradition of respect for the rule of law and belief in diversity of thought, as well as a larger appeal to everyone, regardless of profession, to help with what Clinton suggested in his keynote address: “expanding ‘us’ and shrinking ‘them.’”

In his welcome remarks, Dean Robert Schapiro acknowledged his role as the weaver of the many narratives that constitute Emory Law.

“I have been honored to meet students and alumni from around the world. You have shared your stories with me and you have challenged me. You have inspired me to make Emory Law a better place, a place of which we all can be proud, and for that I am very grateful," he said. "Tonight we honor our past and dream of our future.”

President Claire E. Sterk touched on several chapters of the school’s early history, including the work of Bishop Warren Aiken Candler, Emory’s chancellor at the time, to establish a vision for that first law class of 26 students.

“Ever since its founding,” Sterk said, “Emory Law has educated its students to create a world that is more just.”

The president went on to talk about Eléonore Raoul’s crafty move, registering for Emory Law in 1917 when Candler was away, yet the rules barring women were still firmly in place. Raoul stayed and became the first woman to graduate from Emory University. “That tells you something about the creativity that comes with the rule of law," Sterk quipped.

She detailed other key moments in the school’s history, including the contribution made by Henry Bowden 34L, chair of the Emory Board of Trustees at the time, and then-dean of the law school Ben Johnson 40L, who successfully argued the case that desegregated Georgia’s private colleges and universities. Three years after that suit was filed in 1962, Emory began to admit African Americans — first Ted Smith 65L, followed by Marvin Arrington 67L and Clarence Cooper 67L.

The president also noted the more modern aspects of the school, detailing the degrees beyond the JD that graduates may earn — including the JM and LLM — as well as the points of intersection law has with professions such as the social sciences, humanities, public health and healthcare.

Sterk also credited the work of the law clinics, which, she said, “fight for justice on the part of people who are so vulnerable, including women and children and our nation’s veterans.” And she remarked on the many joint degrees available to Emory Law students, including those with public health, theology, business and the graduate school.

As Sterk concluded her comments, she urged attendees to, “Keep in mind these words from a father of an Emory alumna: ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.’”

Those were, of course, the words of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the father of Rev. Dr. Bernice A. King 90L 90T, who earned one of the joint degrees the president highlighted.

King also invoked her father as she gave the evening's invocation, asking that the assembled pursue his dream of a “more beloved community.”

Nunn finer

Taking the stage to help honor former U.S. Sen. Sam Nunn 61L 62L with a Lifetime Achievement Award, Clyde Tuggle, senior vice president and chief public affairs and communications officer for The Coca-Cola Company, explained to the crowd, “Emory students come into the university with a Coke in their hands and leave with one as well.” In addition to the Coke toasts that welcome new students and honor graduates, the tradition marks milestones across the university.

Tuggle thanked President Clinton for making the trek from the “empire state of the North to the empire state of the South” and then turned his attention to Nunn, who spent 24 years representing Georgia in the U.S. Senate. During that time, he served as chair of the powerful Armed Services Committee and chair of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

His legislative accomplishments include the Department of Defense Reorganization Act and the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program, which provided assistance to Russia and the former Soviet republics to secure and destroy their excess nuclear, biological and chemical weapons.

“In 1997, he retired from public office but not at all from public service,” Tuggle said, and that is borne out by the fact that Nunn currently serves as co-chair and CEO of the Nuclear Threat Initiative, an organization working to reduce the threats from nuclear, biological and chemical weapons. He is also a distinguished professor in the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at Georgia Tech.

Thanking Nunn for “the work that he has done to free the future from the shadow of nuclear incidents, terror and warfare,” Tuggle asked the audience to raise the Cokes at their tables to “this proud son of Emory, a man of towering character and undersized ego, a relentless warrior for understanding security and peace, and truly a leader deserving of your recognition as a recipient of the Centennial Lifetime Achievement Award.”

100 who shaped Emory and the world

Nunn was not the only Emory Law alumni honored for the school's centennial. During the gala, Schapiro recounted the names of those who had received alumni awards at a separate earlier event. The dean then turned to the Emory Law 100, a list of alumni who "celebrate the best of Emory Law, past and present. The list honors alumni and faculty for advancing the rule of law, making history at Emory or beyond, or significantly enhancing Emory or the Emory Law community.”

The full list, along with short biographies of the winners, is available here.

To kick off the Emory Law 100, an impressive intergenerational pairing brought Judge Clarence Cooper onstage with Janiel Myers 18L, who recently became the first

black editor-in-chief of the Emory Law Journal, the law school’s oldest publication.

Myers presented the Emory Law 100 medal to Cooper, who after being one of Emory's first African American graduates, went on to become the first African American assistant district attorney hired to a state prosecutor's office in Georgia and then senior judge on the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia.

Susan Clark, the law school's associate dean of marketing and communications, and Ethan Rosenzweig 02L, dean of admission, financial aid and student life, read the names of the other Emory Law 100 honorees who were in the audience. As they did so, student ambassadors were at tables to honor the winners with medals. Martin Worthy 41C 47L, celebrating his 70th year as an Emory Law alumnus, earned an affectionate response from the crowd as he received his.

As Chilton Varner 76L, an Emory University emerita trustee and Emory Law distinguished alumna, introduced Sam Nunn, she emphasized that “he has been a leader his entire life.” Varner had the audience chuckling as she revealed that Nunn’s transfer to Emory after three years at Georgia Tech saved him from a “lifetime of trying to master mechanical drawing” as part of his engineering program.

She quoted Nunn himself on his early-career transformation, saying, “I dropped into law school, descended into the practice of law, and sank into the depths of politics.” When describing his work in the Senate, she offered, “Time and time again he reached across the aisle in demonstrations of bipartisanship that would be literally unimaginable today.”

When Nunn spoke, he evidenced the modesty that Varner had extolled, as he paid homage to President Clinton and offered words of thanks to Emory Law, saying many of the Emory Law 100 are “my heroes.”

As lighthearted as he was in regard to himself, Nunn was serious about promoting civility as a remedy for what is wrong in the current political climate. Praising our system of government and its checks and balances, Nunn said that it compels us to work together to overcome differences.

“We are in a race between cooperation and catastrophe here and abroad," he said. "Can we restore civility in our political system? Today in America, this is an open question.”

A welcome return

After Nunn's remarks, Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed dropped by to offer “hearty congratulations to the school” and to Sterk and Schapiro for their leadership. Reed, drawing laughs, called himself “the sorbet between two extraordinary courses,” nestled as he was between Nunn’s appearance and Clinton’s.

Describing the night as a “historic and powerful moment,” Reed thanked the Emory administration, faculty and student body for all that they have done for the city of Atlanta. “I bow in honor of you,” he concluded, “and all your contributions.”

Sam Feldman 18L, student body president for the coming academic year, then introduced the 42nd president of the United States, Bill Clinton. Talking about his class and the challenges of the next century, Feldman said that he and his fellow students must do three things: look to each other; look to the law school’s distinguished alumni; and look to those “lawyers and leaders who share in the pursuit of our common goals, and in doing so we renew our commitments to ourselves and each other to become trailblazers when there is no path and problem solvers when there is no easy solution.”

It has been 22 years since Clinton’s last visit to Emory for an economic conference that the White House staged at Cannon Chapel. He began by talking about the Emory Law graduates he had advanced during his administration, including five judges and two ambassadors. He also described a high point of his White House years being a meeting of Nelson Mandela with American church leaders, including Bernice King.

Clinton recalled that he was still governor of Arkansas when he met Nunn and took over leadership of the Democratic Leadership Council from him. The two men didn’t always agree.

Clinton noted a trip that he sent Nunn, former President Jimmy Carter and former chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell on in 1994 to ease out Haitian military dictator Raoul Cédras. None of the three men was particularly excited about the assignment, especially Nunn.

“I told them to go down there and let it be known that they disagreed with me,” Clinton said. “Because when you have rule of law and a free society, you can have disagreements.” As a result of the group’s negotiation skill, the transfer of power there happened peacefully.

When Clinton spoke of the achievement of the Nunn-Lugar Act, he reminded the audience that American taxpayer money went to secure the nuclear assets of the former Soviet Union.

Declaring that it was “worth every penny,” Clinton continued: “I don’t know if we could pass something like this today. It was not a world of alternative facts, but a world of alternative arguments.”

Getting an early start on the next 100

That point set Clinton’s path for the remainder of the evening, as he talked about the ways that “we can recover our balance in America.” He talked about the Presidential Leadership Scholars Program, which he set up with former President George W. Bush, that puts people of very different perspectives together out of the conviction that “diverse groups make better decisions than homogeneous ones.”

Both Nunn and Clinton are men who still care deeply about national life. Both believe that we must listen better to one another. “We get periodic fevers," Clinton explained. "Countries have emotional lives, but it is well that the illness not go undiagnosed.”

In his words and those of Nunn, it surely did not. Even better, Clinton clearly saw a remedy in what Emory Law offers.

He closed a night of singular inspiration with these words: “We would be better off if Emory Law, in the past 100 years, had educated even more people about the weight of evidence, the strength of argument, the balance of logic and passion, and the goal of equal, fair and honorable treatment — and of expanding ‘us’ and shrinking ‘them.’”

“So go do it,” he implored. “You’ve got another 100 years.”