Think of one of the most difficult countries on the planet to enter, one that wards off visitors with a hostile government plus barriers of language and religion, and yet one that holds the promise of exotic sights and incredible discoveries

An exhibition at the Michael C. Carlos Museum features one of those countries: Greece, that is, the way Greece was for 400 years from the mid-1400s to early 1800s. Trying to get into Greece was almost like going into Soviet Russia in the height of the Cold War.

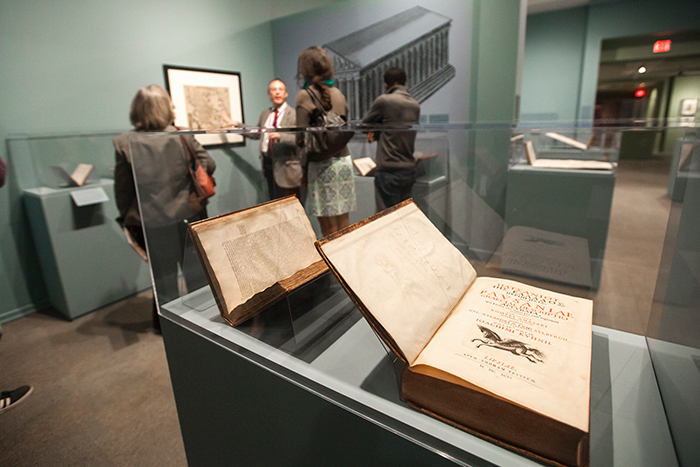

“In Search of Noble Marbles: The Earliest Travelers to Greece” brings together the first published accounts of European travelers to that nation in the form of travel books, maps and illustrations.

“This exhibition is the richest documentation of this particular story to be put together in a generation,” says Jasper Gaunt, the museum’s curator of Greek and Roman art, noting that the quantity of material is relatively scarce and inaccessible. “Not many people went and came back. Not that many people wrote up what they saw. We’ve got about 60 percent of what there is.

When the Ottoman Empire conquered Greece in the 15th century, its hostile governing style and differences in language and religion closed off Greece to the rest of the world.

“A wonderful illustration of just how remote Greece was at that time,” Gaunt notes, is found in “The Nuremberg Chronicle,” published in 1493, which recounts world history as related in the Bible.

This book contains “a fanciful idea of what Athens looked like. It’s a walled city with a church, a river flowing by it. It’s got a hill. This is exactly like all the other illustrations of the towns in Germany along the Rhine,” Gaunt says.

“The people who were making this in the 15th century had no idea what Greece looked like. It was just a fantasy,” he explained.

“The Nuremberg Chronicle” is one of the treasures belonging to Emory’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library on loan to the museum for this exhibition. Other books in the exhibition are from the Pitts Theology Library and from Andrew Oliver, museum curator and lifelong collector of books about early travelers to Greece.

Exhibit features

"In Search of Noble Marbles" also includes a series of other books, maps, drawings, photographs and more. Highlights include the following:

• A book by 2nd century Greek travel writer Pausanias, what the very first travelers venturing into Greece in the 16th and 17th centuries took for a guide.

Despite being centuries old, Pausanias’ book, a copy of which also belongs to the Rose Library, hasn’t gone out of use or print. “You can buy it in Penguin today, a translation,” says Gaunt. “I have been to Greece with an English translation and it is a wonderful thing as you walk up the Acropolis holding a copy in your hand, reading that the Parthenon is on your right – and it is.”

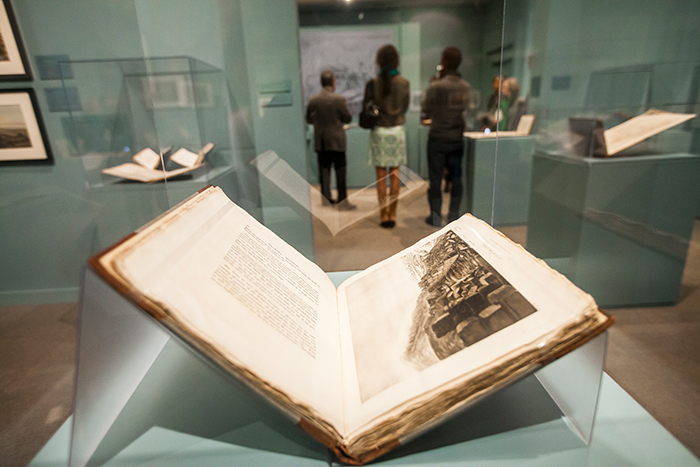

• A description and illustrations of the Parthenon before it was blown up in 1687.

“These are two of only three or four images we have of [the Parthenon] before disaster came when the Venetians laid siege to the Acropolis, which had been turned into a Turkish fortress. There was gunpowder in the Parthenon and they shelled it,” Gaunt says.

• Drawings by a French artist, Jacques Carrey, of the Parthenon sculptures, the only way they became known to future generations of scholars and travelers.

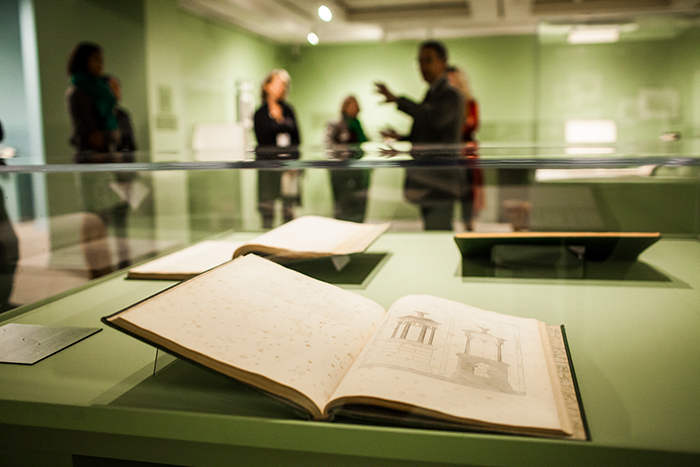

• The first and second editions of a three-volume set made by British travelers James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, who were paid to go to Greece and make measured drawings of the monuments.

Among the most influential books of their day, the volumes contain “hundreds of these very detailed architectural drawings on a very minute scale and they are absolutely accurate," Gaunt says. “Many great houses in England, France and this country are built straight from these drawings. The volumes are beautiful copies with huge margins; Benjamin Franklin was a subscriber and you can see why so-called Greek Revival architecture in this country looks the way it does.”

• Maps by 17th century Dutch cartographers featuring extensive detail around the outline of the country. However, “some things are badly wrong,” says Gaunt. “You would not want to get on a boat today with some of these maps and head out.

• A copy of “Childe Harold,” the poet Byron’s largely biographical long poem. The most famous poet of his day, Byron lived and died in Greece fighting for Greek independence.

The exhibition holds an account of Byron’s last days and a picture of the house in which he lived.

• Lithographs by Edward Dodwell who produced over 1,000 drawings with some views of Athens at the time; the interior of the so-called Temple of the Winds, a famous Athenian monument; luminous views over the plain of Thermopylae where the great battle between the Greeks and the Persians was fought; and the famous Castalian spring in Delphi.

• Photographs of Olympia, the site of the Olympic games and the first map that was drawn of it. “People kept trying to go there but couldn’t find it because it’s in a river valley. It had silted up,” Gaunt explains. “It was only in the early 19th century that an English explorer finally found it.”

• A stereoscope with photographs to view the Temple of Bassae, showing historical views from different vantage points.

Stepping into the next room from the one with the photographs, visitors find an unrelated exhibit — unrelated “except that the technology has moved from the still image to the moving image,” says Gaunt, adding, “it’s conceived as a kind of lighthearted coda.”

It features a series of movie stills made, Gaunt says, for quite well-known movies with distinguished actors and actresses and distinguished directors from subjects on Greek mythology. Stars like Richard Burton, Kirk Douglas and opera singer Maria Callas in her only film role are on exhibit.

Three of the film subjects are takes on the Orpheus story, the musician who wants to try and bring his wife back from the Underworld. A vase from the museum’s collection with this same subject sits in the center of the room.

“In Search of Noble Marbles: The Earliest Travelers to Greece” runs through April 9. Museum admission is free for Emory faculty, staff and students. Visit the Carlos Museum website for hours and information on programs and other exhibitions.