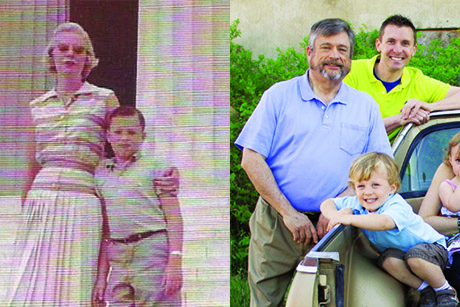

When he was a child, doctors predicted that Bob Harris would die as a teenager.

Despite the fact that his blood didn't clot normally, however, his parents refused to coddle him. They also actively advocated for more resources for hemophilia patients in Georgia.

Aging was new territory for hemophiliacs, and as Harris embraced marriage, traveling, and hobbies (including, ironically, knife collecting) as a young man, he met Sidney Stein, a hematologist at Emory University Hospital.

At that time, in the early 1980s, Stein was becoming the point person for Georgia families seeking the latest discoveries in benign blood disorder research.

Sidney Stein

Harris, Stein said, would need to make some long-term changes, starting with no more nail biting. As the years went by and Harris continued to push his limits, Stein remained blunt and always thorough. Stein's dedication to clinical care, research, and education helped lead to longer lives for hemophilia patients treated at Emory and to Emory's adoption of a national model for the care and treatment of people with hemophilia."The passion in his tone has grown over the years, despite the risky things I've done, like two knee replacements and several surgeries," says Harris. "I've probably given him heart failure, and he's challenged me."

Harris, 66, is alive because of the surge in research and knowledge around hemophilia. And his grandson, Mason, who also has the disease, can expect a brighter future in part due to his family's advocacy.

The Emory/Children's Healthcare Hemophilia Treatment Center is one of the largest of its kind in the country. Its director, Christine Kempton, is a national leader in the treatment of bleeding disorders, and four Emory researchers have gone on to direct hemophilia centers in other cities.

Because patients with blood disorders who see a broad spectrum of specialists lived longer than those treated by a hematologist in a private setting, Stein set up Emory's clinic for holistic care. Because so many patients did not know they needed comprehensive care, he advised Hemophilia of Georgia on hiring outreach nurses, who visited patients at home. This made Emory's bleeding disorder program the first in the country with a public health outreach component. "We have been very fortunate to have what we have," says Patricia Dominic, retired CEO of Hemophilia of Georgia.

The clinic's establishment in the 1980s coincided with the beginning of the HIV epidemic, which devastated the nation's blood supply. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was instrumental in the first successful techniques to treat clotting factor to prevent the spread of HIV. Stein worked with the CDC and reviewed the techniques and products that promised to scrub the blood clean of HIV and hepatitis C. Through this scrutiny, countless recalls of blood were avoided and lives were saved.

Stein helped create the Hemophilia Hotline, a 24-hour physician-to-physician service for Georgia doctors who need emergency treatment information. Nine hematologists across Georgia staff the hotline. "We've been able to take the management, treatment, and cure for hemophilia forward in ways that I personally could never have done without Hemophilia of Georgia," Stein says. "Its focus is Georgia, but the difference it makes is national."

To prevent bleeding, people with hemophilia inject a protein (factor VIII or factor IX) into their blood; the clotting factor is obtained through for-profit specialty pharmacies or nonprofits such as Hemophilia of Georgia.

About 30 percent of people with severe hemophilia A develop antibodies to factor VIII and keep it from working correctly. Pete Lollar, the Hemophilia of Georgia Chair in Hemostasis, has worked for more than 25 years to understand the basic mechanisms of this type of bleeding and to develop a genetically modified factor VIII.

Lollar's team developed and received FDA approval for a synthetic factor VIII product called Obizur, which helps patients who have developed antibodies to factor VIII. Emory research led by H. Trent Spencer and Christopher Doering could lead to the development of gene therapy for patients with hemophilia and the end of daily injections.

"Before, patients would wait to bleed before they injected themselves with clotting factor," Stein says. "Now they inject before they bleed. National data shows that there is much less joint destruction, and they are able to lead more normal lives. When you couple that with other new treatments, patients may soon be injecting only once a week instead of three times, and that's big. One day patients may rarely have to inject themselves at all."