It’s been 94 years since Coca-Cola heir Asa Griggs “Buddie” Candler Jr. created a stately mansion on a 42-acre estate about a mile from Emory University’s leafy Druid Hills campus.

Long abandoned as a private residence, the home that came to be called Briarcliff Mansion would see decades of wear — through various incarnations — before Emory purchased the property in 1998.

Now in decline, the grand manor that sits along Briarcliff Road has been effectively mothballed, primarily used as a colorful backdrop for film and television projects.

But a proposal by an Atlanta developer is poised to breathe new life into the historic mansion, noted as much for its eccentric past as its wood-paneled walls, vaulted ceilings and carved marble fireplaces.

Republic Property Company Inc. plans to rehabilitate the fading property into an upscale 54-room boutique hotel and event venue. The Georgia State Properties Commission approved the proposal Dec. 15, clearing the way for the project to begin.

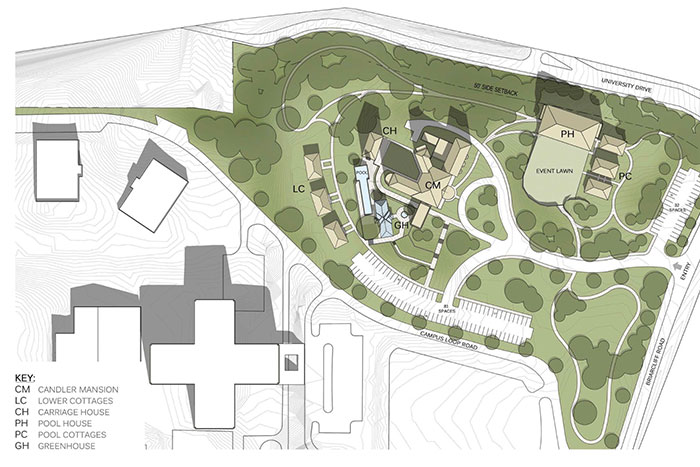

The proposal calls for restoring the mansion, a large greenhouse and carriage house, as well as building seven new structures to support the property, including separate guest cottages, an outdoor swimming pool and pool house, and event catering operations — all inspired by the mansion’s original architecture, according to Rawson Daws, vice-president of Republic Property Company.

In addition to hotel rooms, the project will feature a full-scale restaurant and lounge as well as indoor and outdoor event spaces for corporate or alumni gatherings, small-scale concerts and recitals, weddings and private celebrations.

“In Atlanta, you see a tendency to tear things down and build new,” Daws says. “But we think the Briarcliff Mansion has character and a great backstory, with the connections of the Candler family to Emory and Atlanta, to support a community-driven boutique hotel.

“Architecturally speaking, the bones are there,” he says.

Proposal offers the right fit

Plans to turn the mansion into a hotel were inspired by similar efforts in Europe and the U.S. to develop historic properties for use “as a linchpin in communities to draw people together,” Daws says.

As an example, he points to the Carolina Inn, a 1924-era building that serves as a hotel on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, as well as similar efforts near the University of the South in Sewanee, Tenn.

Under the proposal, Emory would enter into a long-term ground lease with Republic Property Company, and Republic would make all of the investments to rehabilitate the mansion, add new facilities and then operate the hotel, says Peter Barnes, interim executive vice president for business and administration.

The development will encompass less than 10 acres of Emory’s Briarcliff Property, which is also home to Emory and Georgia Tech’s shared Library Service Center and assorted buildings, he notes.

Over the years, organizations have approached Emory with development proposals, though none advanced, according to Barnes. When Republic Property came to the university earlier this year with their concept, the project offered a good fit, he says.

“We wanted something that would be tied to our mission and vision while respecting the integrity of a historical site,” he says.

“With outside funding to support the necessary rehabilitation, the mansion has the potential to be an asset for Emory and the greater Druid Hills community,” Barnes says. “We look forward to seeing it restored to its former grandeur.”

With the support of community organizations including the Druid Hills Civic Association and the Georgia Trust, the application to revitalize the property was approved last month by the DeKalb County Historic Preservation Commission (DCHPC), confirms Amber Rhea, architectural historian at the Georgia Department of Transportation and a member of the DCHPC.

“It was definitely a welcome application,” she says. “We were really happy to see something being done with the property with a proposal that respects its historic integrity.”

The proposal then had to go before the Georgia State Properties Commission. With that approval now in hand, work could begin as early as summer 2017, with completion anticipated late in 2018, Daws says.

Briarcliff’s storied history

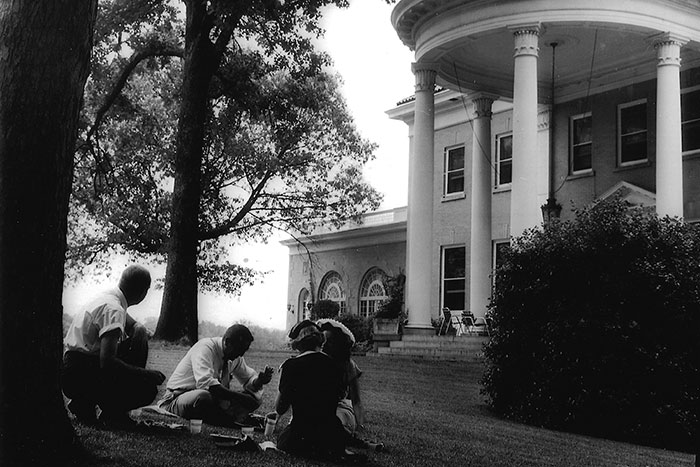

In its day, Briarcliff Mansion was a showstopper — among a string of aristocratic residences built by the sons of Coca-Cola co-founder Asa Griggs Candler, including today’s Callanwolde Mansion (Charles Howard Candler) and Lullwater House (Walter Candler), which has served as the home of Emory’s presidents since 1963.

Emory's ties to the Candler family run deep within the university’s history, says Gary Hauk, Emory historian and senior adviser to the president.

Asa Candler donated $1 million to help establish Emory University’s Atlanta campus and also helped develop the Druid Hills neighborhood it now sits within.

Methodist bishop Warren Candler, Asa's brother, not only graduated from Emory College in 1875, but became the college’s tenth president and first chancellor of the new Emory University.

Buddie Candler, Asa Candler’s second oldest son, also graduated from Emory College. “In a 1926 alumni directory, he lists his occupation as ‘capitalist,’” Hauk notes.

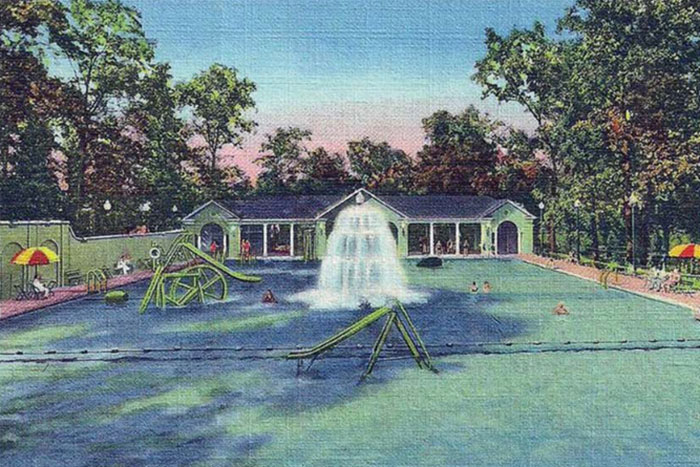

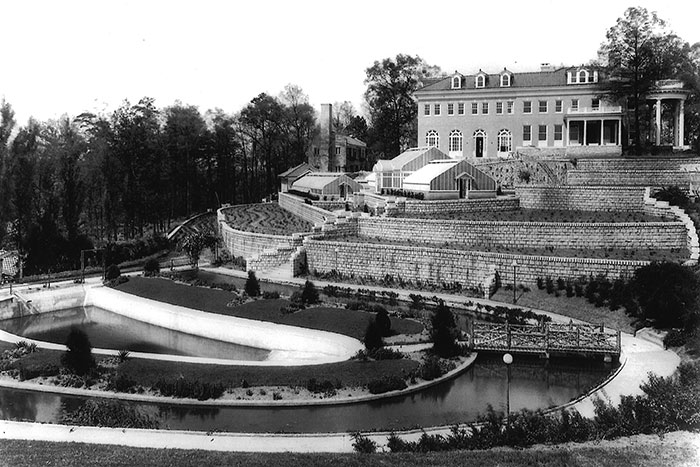

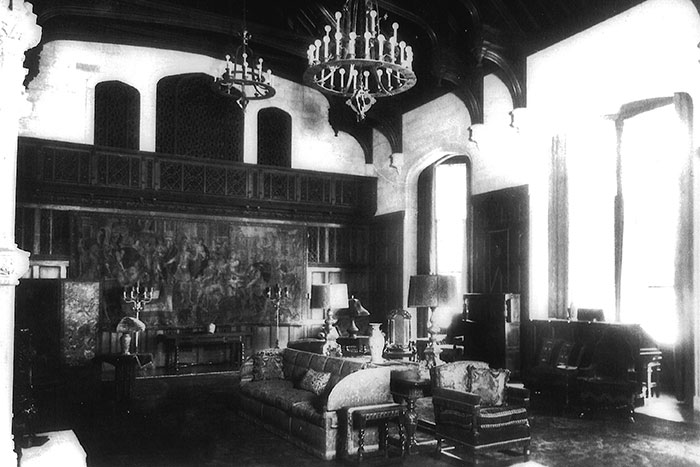

His mansion originally featured more than 40 rooms, two pools, a greenhouse and formal gardens, multiple dining rooms (one alone seated 75 people) and a third-floor ballroom. Later additions included a lavish 1,700-square-foot music room with a cathedral-sized organ (since moved) and a sun-dappled wing built expressly to host a daughter’s wedding.

Architecturally, the mansion represents an eclectic mash-up of styles, notes Emory University Architect Jen Fabrick. A modest Georgian Revival exterior gives little hint of its richly classical interior, with elaborate Tudor features and heavy Italianate carvings reflecting the Paris-inspired Beaux Arts movement that swept America in the early 1900s, she says.

Ten years after moving into Briarcliff Mansion, Candler added to the ambience by importing $50,000 of exotic animals, trucked by way of the nearby Emory train depot.

The menagerie was said to include baboons, lions, tigers, leopards, zebra, bears, buffalo, elk and deer, rare birds and four elephants named — according to legend — Coca, Cola, Delicious and Refreshing. Candler’s private zoo was eventually opened to the public, along with one of the estate’s pools, which was used for many years by children in the surrounding neighborhood.

In time, the zoo’s sounds and smells drew the attention of neighbors. In 1935, Candler donated the animals to Atlanta’s Grant Park Zoo, more than doubling its population and providing its first tiger, according to Zoo Atlanta.

Promise of restored grandeur

Candler, who became a real-estate developer, sold the mansion to the General Services Administration in 1948 with tentative plans to house a veteran’s hospital. Instead, the property became the Georgian Clinic, considered among Georgia’s first alcohol treatment facilities, and later, the DeKalb County Addiction Center, according to Fabrick.

In the 1960s, Emory helped the state develop the Georgia Mental Health Institute (GMHI) to assist patients who couldn’t afford private care. When the GMHI closed in 1997, Emory bought the property to house various programs, Hauk says.

By the time the university acquired the mansion, its elegant sweeping rooms had been carved into cubicles, telephone cords had been stapled into paneled walls, tiles were broken, and plaster was cracking, he recalls.

“The day we took possession, it was already in bad shape,” Hauk says.

Over the past decade, film crews for shows such as “The Vampire Diaries” have typically been granted access under the condition that they helped with cosmetic cleanup or other maintenance.

“As much as we may have wanted to, the size of the financial commitment required to clean it up was always a challenge,” Hauk notes.

“The proposal of having a really magnificent property that is available to the public is a wonderful opportunity,” he says.