In the summer of 2010, electrical engineer Ketan Thanki was in a specialized intensive care unit at Emory University Hospital, waiting for a heart transplant.

One night, he developed signs of an infection. Because he was sound asleep, he had no idea how dangerous his situation had become.

Thankfully, somebody else did.

"The night nurse woke me up and said I had both a fever of 104 and blood pressure of 60 over 30," he says. "She said she needed to start me on intravenous antibiotics right away."

The nurse had recognized the symptoms of sepsis, an extreme response to infection that can result in organ damage, organ failure, and death. Thanki's low blood pressure was a sign that inflammation within his body was intensifying and affecting his circulation.

The mortality risk for someone who develops sepsis is 15 to 30 percent, higher than the risk for someone who has a heart attack. Sepsis is a leading cause of death in American hospitals and the most expensive condition treated there, accounting for more than $20 billion in health care costs annually.

Due to Thanki's prompt treatment with antibiotics, his infection resolved within a few days and he was able to get the heart transplant he needed.

His experience makes detecting sepsis sound pretty straightforward, yet it sometimes goes unrecognized by medical caregivers until it is too late to intervene effectively.

Sepsis stems from an infection, which then leads to a life-threatening abnormal response of the body to the infection. Pneumonia, urinary tract infections, appendicitis, or an infected scrape could all lead to sepsis.

Symptoms include: shivering, fever or feeling very cold, extreme pain or discomfort, clammy or sweaty skin, confusion or disorientation, shortness of breath, rapid breathing, and high heart rate.

Part of the problem in recognizing sepsis, doctors say, is that it can affect all types of people, and its symptoms don't focus on one part of the body. A sepsis patient can be a young athlete, an elderly person in a nursing home, or a patient in the hospital being treated for something else. "The biggest risk factor is already being sick," says Craig Coopersmith, an Emory critical care specialist who, with colleague Greg Martin, was part of an international effort to redefine sepsis.

The new definition, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, clarifies terms and clinical criteria to prompt quicker recognition and treatment.

And, perhaps due to rising awareness of the threat, it has proven quite popular: At nearly 1.3 million views, it is currently the fifth most-viewed JAMA paper ever.

Reshaping sepsis care

"If someone's having a heart attack or a stroke, what's happening is easier to grasp," says Coopersmith. "Everyone knows that treatment is urgent in that situation."

Sepsis response, he says, is equally urgent.

In August, the CDC declared sepsis a medical emergency, and reported that about 72 percent of patients with this fast-moving illness had recently been seen by doctors and nurses, representing missed opportunities to catch it.

Consider young Rory Staunton. In 2012, 12-year old Rory cut his arm diving for a basketball at school in New York City. The next day, he went to the emergency department in a hospital there, vomiting and complaining of leg pain. At that time, doctors thought Rory had a simple flu-like illness. He was given fluids, advised to take Tylenol, and sent home. After he left the hospital, results from lab tests showed signs of severe infection in his blood. Three days later, he died of sepsis, despite strenuous efforts to save him.

To avoid such tragedies, academic medical centers like Emory have taken steps toward improving recognition and starting immediate treatment.

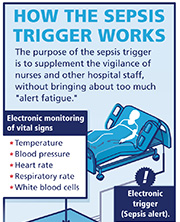

Emory is reshaping how its sepsis care takes place. That means reorganizing teams so that tests and supplies can be delivered more quickly, getting doctors to agree on a standard treatment regimen, and putting into place an "electronic trigger."

The trigger is a computerized version of the perceptive nurse who woke Ketan Thanki up in the middle of the night. Due to Thanki's pending transplant, he was being monitored very closely—his blood was drawn twice a day, and information was being provided to his medical team via a Swan Ganz catheter in his heart. So when Thanki developed signs of infection, hospital staff detected it right away.

The purpose of the electronic trigger for sepsis is to broaden that monitoring so that patients all over the hospital, not just in an intensive care unit, can be caught in its safety net.