Two of Emory University’s Woodruff Scholars are headed to the United Kingdom next year as winners of the prestigious Marshall Scholarship.

Noam Kantor and Emilia Truluck have proven to be accomplished researchers and student leaders at Emory, and will meet again at the University of Oxford in 2017.

Kantor, who will earn his dual bachelor’s and master’s degree in mathematics this spring from Emory College of Arts and Sciences, plans to earn a second master’s degree in math, studying number theory, from Oxford.

Truluck, who graduated in May from Emory College with highest honors with a bachelor’s degree in women’s, gender and sexuality studies and Middle Eastern and South Asian studies, is now in Jordan on a Fulbright grant. She plans to earn a master’s in Refugee and Forced Migration Studies in one year at Oxford, then obtain a master’s degree in gender and sexuality from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London.

“Emory is proud of the well-deserved recognition of Noam and Emilia as 2017 Marshall Scholars,” says President Claire E. Sterk. “During their studies here, they embraced learning, discovery and volunteerism, and their continued studies will allow them to deepen their dedication to make a difference in our world.”

Kantor and Truluck are among 32 U.S. students selected as Marshall Scholars this year, out of 947 applicants.

“Noam and Emilia truly embody the ideals of learning in the liberal arts in the way they both push the boundaries of knowledge and discovery,” says Michael Elliott, interim dean of Emory College and professor of English. “I admire the diversity of their intellectual interests, and I am inspired by their deep sense of curiosity about the world.”

Funded by the British government, the scholarship recognizes high-achieving scholars by covering all expenses for up to two years of postgraduate studies in the U.K. program of their choice, with the goal of nurturing future leaders and strengthening British-American collaborations.

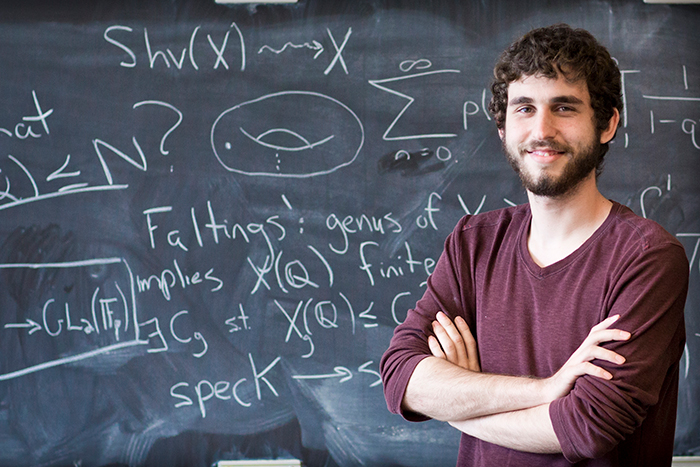

Kantor: Applying abstract math to real-world problems

The opportunity for Kantor to effectively start his PhD at Oxford in number theory is all the more remarkable given that he says he “hated” number theory before Emory.

A branch of math that tries to find interesting and unexpected relationships between different sorts of numbers and to prove that these relationships are true, number theory just seemed too random to him.

But he drew attention from Emory College’s Department of Mathematics and Computer Science — with several specialists in number theory — on a campus visit during high school, says David Zureick-Brown, an assistant professor in the department.

An arithmetic geometer, Zureick-Brown was impressed that the largely self-taught Kantor understood enough about pure mathematics to know what questions to ask. He and other professors set about recruiting Kantor, promising to teach him the more complex number theory right away at Emory.

“His second semester on campus, he was in a reading course on a senior level, and by his second year, he was completing graduate level work,” Zureick-Brown says. “He was always very enthusiastic. He will be even more competitive after Oxford because he understands you can never have too much mathematical knowledge.”

Kantor has previously earned international honors for his work. He was named a Goldwater Scholar in his sophomore year and earned high honors his junior year in the prestigious Budapest Semesters in Mathematics.

Kantor credits Emory for allowing him to pursue his passion with guidance. Specifically, he is interested in solving equations that use only whole numbers — a specific effort within number theory.

The level of difficultly of creating and proving those formulas allows him to think deeply about potential problems, such as cybersecurity or credit card fraud, and how the complexity can help keep us safe.

“Now I see the structure and the beauty in it, and can see people working on my ideas in real life,” Kantor says.

Kantor has proven to be an ambassador of sorts for mathematics, lecturing in courses as well as explaining his work with campus groups he joined.

His sophisticated understanding of math was complemented by studying modern Jewish thought with religion professor Michael Berger, who remembers his student as prepared and engaged both in and out of the classroom.

The course was devoted to the philosophy of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, who wrote that math and physics are not just part of a religious worldview but an integral part of understanding divine will.

Kantor continued to discuss those thoughts outside of class, and in the years that followed, incorporating the ideas in talks about Jewish life, Berger says.

“Math describes a reality we can’t really touch, but is the basis for our modern world,” Berger says. ““I think Noam’s pursuit of math comes from a universal curiosity of the world. If something bothers him, he will keep at it until he figures it out. He’s not someone who will be satisfied with getting by.”

Kantor says he felt stronger in his own Jewish faith when he engaged in its religious traditions. He worked through questions beyond math by getting involved with Hillel, the Inter-Religious Council (IRC) and his fraternity, Alpha Tau Omega.

And, he tried to show the value of those connections by spearheading an initiative to take Emory’s Campus Couches program into Atlanta. For that, he coordinated installing two sofas on Peachtree Street, encouraging strangers to sit and talk to learn about each other.

Kantor puts himself in the same situation, both with Campus Couches and Table Talk — two Emory programs — and with the International Rescue Committee.

“We have different values, and we shouldn’t minimize that as we learn about our similarities,” Kantor says. “My math hero is Alexander Grothendieck, who understood that the only way to solve the hardest problems is to return to the basics. That's daring and it's something many people won't stoop to."

Truluck: Putting scholarship into action

Truluck’s advisers and mentors describe her as curious — and unrelenting. Her Marshall Scholarship is a further testament to her motivation, given that she was an alternate last year and applied again for the win this year.

That determination and courage was clear to Pamela Scully, a professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies and African studies, when she learned her student had been dual-enrolled at the State University of West Georgia for her final two years of high school.

Truluck, who grew up near Savannah, lived across the state in Carrollton for the program and maintained a perfect GPA while carrying a full college class load.

“Emilia is someone who is interested in the world,” says Scully, who taught Truluck in both first-year and senior seminars. “She is independent, and she does not give up.”

Truluck, answering questions by email from Jordan, says she found her career path after becoming involved with Volunteer Emory as soon as she came to campus.

She had previously worked with immigrants learning English as a second language, but being a staff volunteer gave her new perspective working with refugees being resettled in nearby Clarkston.

That work and her studies prompted an interest in the ongoing Palestinian refugee issue and the treatment of refugees in the Middle East, particularly those who are living without the benefits of citizenship for protracted periods of time, she says.

Already conversational in Spanish, Truluck aimed to improve her Arabic language skills by spending a summer abroad at Al Akhawayn University in Morocco.

She used her language skills as a research assistant in Emory’s law school with Abdullahi An-Na’im, Charles Howard Candler Professor of Law. With her focus on human rights, she was also named an intern in the conflict resolution program at the Carter Center.

Her focus on Jordan happened by accident, when she petitioned to study abroad again, this time at Al Quds University in East Jerusalem. When that was denied, she ended up in Jordan for Emory’s first approved program there.

“I was pleasantly surprised to find out that a major part of the Jordan program was exploring the treatment of refugees in the country,” she says of the country that has historically served refugees from the region and is currently struggling with those fleeing Iraq and Syria.

“Jordan, as a resource-poor country, heavily relies on international aid to support these refugees, so Jordan is a really interesting country for examining how international non-governmental organizations work in the field to support refugees who are both historically stateless and newly displaced,” she adds.

While there, Truluck became interested in the experiences of refugee women, in particular. During her first visit, she completed a small project, comparing the street harassment of Jordanian women and Syrian women.

The surprising findings revealed the vulnerability of Syrian refugee women to harassment by other refugees, Jordanians and, disappointingly, international aid workers. The project inspired her senior honors thesis and current Fulbright work.

“Emilia’s quest for excellence extended far beyond the classroom,” says Elizabeth Fessenden, the senior program associate for the Emory Scholars Program. “Her deep involvement with Volunteer Emory as a weekly service trip leader and as a Social Justice Dialogue coordinator demonstrated her desire to actually change the world. I have no doubt that she will do exactly that.”

After graduation, Truluck spent her summer volunteering as a case assistant with Lutheran Services of Georgia’s refugee program in Savannah.

She recently completed three months of more extensive Arabic language skills at Qasid Arabic Institute in Amman while also volunteering at a United Nations school serving Palestinian refugees. Starting in January, she will spend nine months focusing on her research about street harassment.

Oxford had already allowed her to defer attending there for the Fulbright. Her time as a Marshall scholar will allow her to further study the roles of international coalitions in addressing the ongoing refugee crisis and will prepare her to work for the UNHCR, the United Nations’ refugee agency, she says.

Her eventual plan is to return to the United States to work on refugee policy here, something Scully says she is sure will happen.

“She wants to think about a problem in order to do something. Emilia takes action,” Scully says. “We will know her name.”