What do history and poetry reveal about ourselves and our times? Rosemary Magee, director of Emory's Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, promised that the University’s “best minds and deepest hearts” would answer the question for the eighth "Neil Asks" event, held Sept. 29.

L. Neil Williams Jr. was a generous donor to the Emory Libraries, a former trustee of the Halle Foundation and devoted to advancing the law, arts and education. The "Neil Asks" series honors his example by “asking important questions … that would guide us toward greater understanding, innovation, service and hope.”

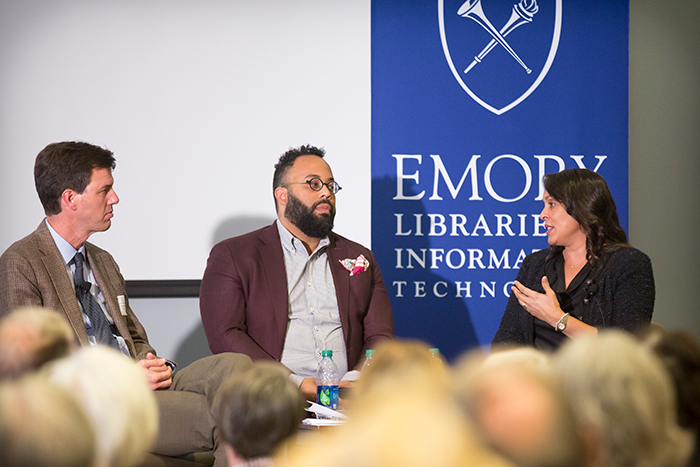

Last week's event drew a standing-room-only crowd to the Jones Room of Woodruff Library to hear from Natasha Trethewey, Robert W. Woodruff Professor of English and Creative Writing, director of the Creative Writing program and former U.S. poet laureate, and Joe Crespino, Jimmy Carter Professor in the Department of History, in a discussion moderated by Kevin Young, Atticus Haygood Professor of English and Creative Writing and curator of the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library.

Their wide-ranging conversation examined the value of poetry and history, the relationships between them, and asked, "Who tells our history best?"

It’s Robert Penn Warren …

Looming large was poet, novelist and literary critic Robert Penn Warren, whose own thoughts on the question framed the discussion. Warren wrote, “Historical sense and poetic sense should not, in the end, be contradictory, for if poetry is the little myth we make, history is the big myth we live, and in our living, constantly remake.”

Young asked Trethewey if poetry is a branch of history, to which she replied, “Poets always, whether intending to or not, are inscribing something about our cultural moment, which is historical.”

Crespino continued that thread, observing that Warren and C. Vann Woodward 30C 63H, the celebrated historian, were among the first to write against the received myths of their generation — namely, of American success and unending progress. The Civil War forever prohibited a sanguine view of history in the South, as the English historian Arnold Toynbee observed when he said:

“[H]istory is something unpleasant that happens to other people. We are comfortably outside all that. … Of course, if I had been a small boy in 1897 in the southern part of the United States, I should … then have known from my parents that history had happened to my people in my part of the world.”

No, it’s William Faulkner … or Robert Hayden

According to Woodward, it was a novelist, William Faulkner, who was the South’s greatest historian. The latter, of course, famously opined in “Requiem for a Nun,” “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Trethewey talked about the poet Robert Hayden, the first African American to occupy the position now known as poet laureate. Hayden wrote, according to Trethewey, “to correct the misapplications of African American history.”

Like Hayden, Trethewey feels an obligation to “tie herself to history.” And she celebrates the fact that the best literature or historical account comments on both the past and present. She cited her own “Native Guard,” which is at once about a regiment of black Civil War soldiers and “also about right now and the contest we have about history.”

Don’t count out Atticus Finch

Crespino is writing a political biography of Atticus Finch, the hero of Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird.” What drew him to the project were “ideas about the change that happened in the American South in the mid part of the century. It was not just about filibustering Southern senators or court decisions to create greater equality, but about stories like ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ stories that we teach our children.”

At the time of its 2015 release, Lee’s “Go Set a Watchman” — thought to be a first draft of “To Kill a Mockingbird” — engendered broad discussion that included Crespino and Trethewey. Said Trethewey, it “broke people’s hearts” that Finch “could be at once someone who believes in justice and the letter of the law and yet, deep down, also believes in racial difference and the status quo.”

Hail to the archivists

Young wanted to know what their greatest discoveries in archives had been. Surprisingly, one of Crespino’s revelations was about Trethewey’s family.

While researching the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, Crespino discovered that Trethewey’s grandmother had tried to place a wedding announcement in 1955 for Trethewey’s white father and black mother. That act earned her an entry in the commission’s rolls. From 1956 to 1977, that body profiled more than 87,000 people associated with the civil rights movement and was complicit in the murders of three civil rights workers in Neshoba County.

For her part, Trethewey talked about what she learned in reading Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass.” “In subsequent versions,” said Trethewey, “Whitman was writing blacks out of his narrative, erasing them. What was that about?”

And, above all, to Emory’s own

Both Crespino and Trethewey agreed that, with history and poetry, “there is always borrowing across the line,” as she noted.

Crespino views that borrowing as a necessity, saying that even with regard to 20th-century history, where we are blessed with so much source material, still “there are so many silences in the archives” that need unpacking, whether by poets or historians.

As the panel drew to a close, Trethewey described a poem that she wrote for the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture about the Sixteenth Street church bombing that took place in Birmingham, Alabama, in September 1963.

Trethewey chose to “go at the incident sideways,” by looking at the history of stained glass. All the church’s stained glass windows were destroyed except for the largest one — that of Christ the Good Shepherd.

In stained glass art, a Vidimus is created — a sketch that envisions the finished product. The translation from the Latin is, “We have seen.” That was the perfect entry point for Trethewey to note that the tragedy is an event to which we all must bear witness.

“Poetry is interested in the facts but also in an emotional truth," she explained. "That perhaps makes it truer than anything else.”

Trethewey’s poem, “We Have Seen: View from the Window of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, September 15, 1963,” appeared in last month’s issue of Smithsonian magazine and is available as an audio file.

She apologized for not having brought the poem to read, but the audience was as moved as if she had. Whatever it is that Crespino and Trethewey do — history, poetry, a blend of the two — there is no doubting its power.