How is it that people living in rural, poor areas of the globe can report being happier than those who live in the relative affluence of the United States?

Emory anthropologist Peter Little and philosopher Mark Risjord aim to answer that question as part of a team that has been awarded a “Happiness and Well-Being” grant. Funded by the John Templeton Foundation and St. Louis University, their work is part of a larger research program in the growing field of well-being.

“The idea is to compare the subjective meaning of the good life and see if that affects the relationship between material well-being and reports of happiness and overall well-being,” says Little, the project’s principal investigator.

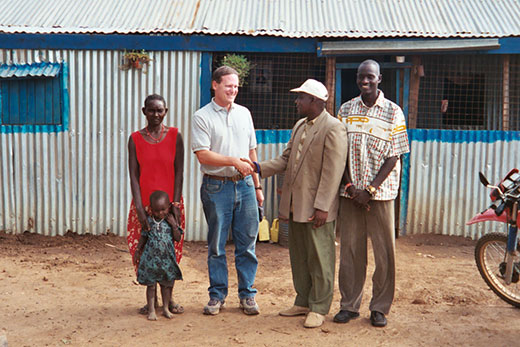

The Emory team’s project, which includes economist Workneh Negatu of Addis Ababa University, will study two specific low-income communities: South Wollo, Ethiopia, and Baringo, Kenya.

Little has long studied the politics, economy and ecology of eastern Africa. When he was completing his dissertation in 1983, there was only one college graduate in the Chamus Maasai community of Baringo, Kenya, where he studied. Since then, there have been significant social changes and there are now dozens of college graduates among the Maasai-related pastoralists population, he says.

That makes that area in Kenya a good place to understand relative well-being and poverty where, as in the U.S., people are poor relative to their neighbors. South Wollo, by contrast, remains populated by those in absolute poverty. A bad harvest there, or lost jobs, still can lead to dire hardships and even starvation.

The United Nations’ annual World Happiness Report this year ranked Ethiopia a dismal 115 out of 147 countries according to citizens’ happiness levels. The United States ranked 13th in the analysis, which looked at factors such as life expectancy, health and freedom from corruption in government and business.

Yet Ethiopia ranked 94th on the 2012 Happiness Index, the most recent available from the New Economics Foundation. The United States ranked 105th in that study, which included a factor called “life satisfaction.”

Kenya, likewise, ranked poorly in the U.N. report, at 122nd, but also bested the United States with a rank of 98 on the Happiness Index.

“This is huge for public policy,” Little says. “Kenya’s therapy industry is starting to emerge, because people’s expectations of what the good life is have changed drastically, and they’re not meeting those expectations.”

Philosophical concepts of well-being

Risjord’s role will be to help provide a philosophical framework for the qualitative study. In his section of the project proposal, Risjord wrote that past study of well-being seems to take sides on longstanding philosophical disputes on whether it is a universal sense or different in different contexts.

Risjord, who is teaching philosophy of science in a Tibetan Buddhist monastery in southern India as part of the Emory-Tibet Sciences Initiative, says his role will be to understand how the feeling varies with context based on historical, cultural and economic data gathered in both Ethiopia and Kenya.

“The philosophical contribution of this project will be to develop a more robust and articulate conception of how human well-being varies with social, economic and environmental context,” Risjord writes in his proposal section.

The study will become part of the larger Happiness and Well-Being project at St. Louis University, which is designed to promote dialogue and collaboration among well-being researchers across a broad range of disciplines.

Little, whose proposal was one of just 21 funded from a pool of 300, says he hopes to begin travel under the $248,000 grant by August.

He will build upon that work back in Atlanta, too. Long-term, he plans to get students to look at the Ethiopian diaspora here, to gauge if their sense of well-being changes when they arrive in the U.S.

“To me, it’s really exciting to do cultural interpretations of well-being and poverty,” Little says. “It’s a fascinating way to look at culture.”