A rare first edition of David Walker's 19th century anti-slavery book, "Appeal," owned and signed by W.E.B. Du Bois, has been obtained by Emory University's Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, with a generous grant from the B.H. Breslauer Foundation and additional support from other individuals.

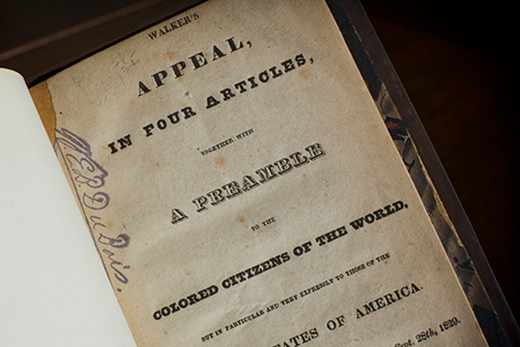

Written and published in 1829 in Boston by Walker, a self-educated African American merchant, "Appeal" is considered one of the most important documents in African American history. Its full title is "Walker's Appeal, in Four Articles, Together with A Preamble to the Colored Citizens of the World, But in Particular, and Very Expressly to Those of the United States of America."

Only half a dozen copies of early editions of "Appeal" are known to exist, and only two known first editions can be found in libraries, according to the Rose Library's curator of research Randall Burkett.

The first edition at Emory is stamped with Du Bois' ownership signature on the title page, and his holograph signature is on the front fly. The book also contains Du Bois' extensive marginal markings.

"One of the most compelling aspects of this work is that it addresses some of the questions that continue to challenge us today," says Rosemary Magee, director of the Rose Library.

Kevin Young, curator of literary collections and of the Rose Library's Danowski Poetry Library, echoed that sentiment in a comment to The New York Times. "The book is testament to a line of black protest and prophecy that stretches from Walker to Du Bois to #blacklivesmatter," he said. "Seeing it and the markings it's almost as if Du Bois's lines in the text make that literal."

In his autobiography, "Dusk of Dawn," Du Bois called Walker's "Appeal" "that tremendous indictment of slavery," recognizing its importance as the first "program of organized opposition to the action and attitude of the dominant white group."

According to the late American historian Herbert Aptheker, "Walker's 'Appeal' is the first sustained written assault upon slavery and racism to come from a black man in the United States." The publication was considered so radical and revolutionary in its call to arms that even abolitionists condemned it as inflammatory.

"The book itself is a landmark of political protest and eloquent articulation of the demand for freedom for people of African descent in the United States," says Pellom McDaniels III, curator of African American Collections in the Rose Library. "It is as important for African American political and social history as Thomas Paine's 'Rights of Man'; it is a demand for freedom and a call to arms."

Walker used networks of African Americans, including black seamen to get copies into the hands of Southern slaves, where it could be read aloud and in secret to small groups, according to McDaniels. He suggests that state and local Southern governments were horrified by the "Appeal" and reacted by arresting and even lynching enslaved and free blacks suspected of owning the publication. To prevent the possibility of insurrection, all found copies were destroyed, he says.

Walker's "Appeal" is among the earliest African American-authored books in the Rose Library's holdings, and the oldest example in the library's collection of material published by African Americans, an area Emory has pioneered. These materials are open to all—including students, faculty and visiting scholars, and are a cornerstone of research and teaching programs.

The Rose Library also holds first editions of Phillis Wheatley's "Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral" (1773), J.A.U. Gronniosaw's "A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, An African Prince" (1790), and Benjamin Banneker's "Almanac" (1793).