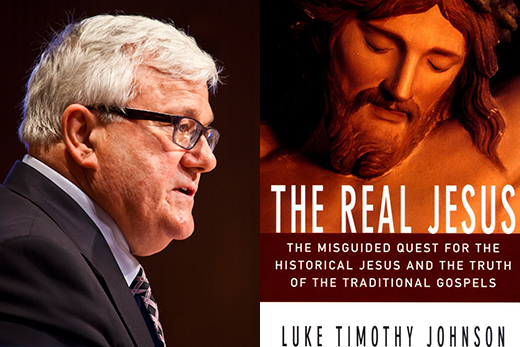

Twenty years ago, Emory University's Luke Timothy Johnson was in the right place at the right time. His 1996 book, "The Real Jesus," became a blockbuster of the Lenten season, making the kind of national media splash that biblical scholars and theologians can only dream of today.

Johnson, the Robert W. Woodruff Professor of New Testament and Christian Origins at Emory's Candler School of Theology, was already a widely recognized biblical scholar, but as he recalled recently, it was "The Real Jesus" that took his career on a different path.

"There's no question that the book had an unanticipated impact both on me and on a lot of readers," says Johnson, adding that he wrote the manuscript in three months, "the quickest book I've ever written."

With publication of "The Real Jesus," Johnson became a leading figure opposing the research and scholarship of the widely publicized Jesus Seminar, a group of some 200 biblical scholars who sought to verify or disprove sayings and actions attributed to Jesus through historical review and analysis.

Johnson, who had written a series of negative reviews of books on the so-called "historical Jesus" movement, was approached by a publisher who had read the reviews and asked him to write a book. Things moved swiftly from there.

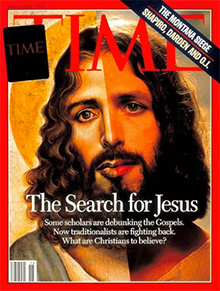

The book was snapped up by both scholarly and general audiences—a mountain of copies disappeared at the annual American Academy of Religion meeting. Cover stories quoting Johnson on the historical Jesus debate and the Jesus Seminar appeared in TIME, Newsweek and U.S. News & World Report. He also was featured in The New York Times and interviewed by ABC, CBS and CNN.

One consequence of "The Real Jesus" for Johnson personally, he says, was "a taste of notoriety that I've never wanted to recover, partly because I realized how intoxicating it was."

"I didn't like it that I liked it too much," recalls Johnson, adding that his sudden fame "distanced me from my students. I had students respond to me as a celebrity rather than as their teacher. It was alienating me from the social context I treasured.

"The scariest thing is that for some students, I was more real and authoritative because I had been on TV," says Johnson.

Because of the media firestorm and its aftereffects, Johnson says he has since eschewed celebrity. Yet his influence continues to be widespread: he is author of 31 books, more than 70 scholarly articles and more than 200 book reviews (yes, he still does them). In 2011, Johnson won the prestigious Louisville Grawemeyer Award in Religion, which carries a $100,000 prize.

This TIME cover story from April 8, 1996, was one of several publications that quoted Luke Timothy Johnson on the historical Jesus debate and the Jesus Seminar. Cover credit: Gregory Heisler

And although he has continued to lecture and write on historical Jesus issues, and on the literary, moral and religious dimensions of the New Testament and early Christianity, the media circus surrounding the Jesus Seminar—and in many ways the theological debate—has moved on, perhaps permanently.

"On the larger issue of the state of historical Jesus studies, the book accomplished something," says Johnson. "I think it broke the momentum of what appeared to be at that time an irresistible force that was perceived as academically approved and ecclesiastically embraced."

That Johnson, an already well-known biblical scholar, would publish a book essentially saying "no, this [historical Jesus scholarship] is bad history; this is bad theology" modified the movement, he says. "From then on, my position had to be taken into account."

He points to the 2009 book, "The Historical Jesus: Five Views" as emblematic of the sea change. "As so often happens, the book included essays by four historical Jesus researchers—and me. There was a time before 'The Real Jesus' when that voice would not have been heard in that volume. So it altered me, and it altered the state of the conversation."

Where historical Jesus research tends to flourish these days is among a segment of believers, which is ironic, given that in Johnson's view, historical Jesus research is still "bad history and bad theology."

It's clear that even 20 years on, Johnson still affirms the book's assertion that "the state of biblical scholarship within the church is in critical condition." What he sees today also does not bode well for the faith.

His 2003 book, "The Creed," was his response to the observation that some Christian believers "seem so little aware of how sloppy thinking erodes and makes ludicrous what is supposed to be the fundamental commitment of their lives.

"If we call the historical Jesus movement and the Jesus Seminar the supreme Enlightenment project," says Johnson, "then my reaction to it and others' reaction to it may also be called the last manifestation of creedal conscience and a sense that the stakes are very, very high.

"Either you're doing real history, in which case everything is up for grabs, or you're doing fake history in which you just make it come out alright," says Johnson.

"In either case you're neglecting the genuine grounds of why you are a Christian or a theologian," he says. "It does not have to do with what Jesus did as a first century 30-year-old male Jew living in Galilee, but has everything to do with God exalting him and making him life-giving spirit to transform human existence."