Dystonia patient Michael Richardson enjoys hiking with his son, Eddie — one of many activities that wasn't possible before his DBS surgery.

Michael Richardson first experienced symptoms of dystonia, a movement disorder characterized by involuntary muscle contractions and spasms, when he was 13.

"When I walked, I would put the toe of my left foot down first. My dad would say, 'Walk right,' but I couldn't change it. Over time, it got worse. My foot contorted. I finally had to use crutches, then a wheelchair on and off," he says. "My arms became involved—my biggest struggle was with writing. I couldn't write at all with my dominant hand, so I learned to write left-handed."

These exaggerated movements are called "overflow"—a common occurrence among dystonia patients, says Mahlon DeLong, William Timmie Professor of Neurology at Emory's School of Medicine.

For example, if dystonia patients are asked to wiggle a toe, their whole leg will start moving. Or if they try to tap their index finger and thumb together, their arm will swing.

"Imagine trying to force two positive magnets together," says Richardson. "The more intent I was on writing, the worse it became." He had the same problems when trying to bring a cup to his mouth, or using a fork to eat.

The son of American missionaries, Richardson spent his teenage years in Mexico, where a pediatric neurologist treated his symptoms with Botox shots and oral medications. This allowed him to walk, but there were side effects to the medication, such as drowsiness.

"Cold, stress, being tired could all be triggers, and the symptoms would get even worse," he says.

Dystonia is the third most common movement disorder, says DeLong, after essential tremor and Parkinson's. "It doesn't get as much recognition because it can occur in so many different ways and locations," he says. "Generalized dystonia is most common in children and young adults, whereas focal dystonias show up later in life and can affect virtually any part of the body—neck, eyelids, jaw, hand . . ."

When focal dystonia does get attention in the media and elsewhere, it is often associated with musicians and artists who can no longer perform the fine motor skills necessary for their craft—violinists, pianists, guitarists, flautists, even visual artists. (Cartoonist Scott Adams, of Dilbert fame, developed focal dystonia in his right hand, which hampered his ability to draw.)

Richardson moved back to the US for college. After graduation, while working for Verizon, he would often find himself typing in phone numbers incorrectly. Even with Botox shots every three months and baclofen, an oral muscle relaxer and anti-spastic agent, he had to use a wheelchair for longer distances and crutches inside the house.

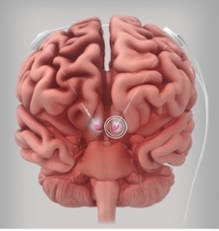

That's when his doctor told him about a surgery available at Emory. Doctors could put electrode leads into his brain and, using a battery, provide deep brain stimulation (DBS) that could reduce or eliminate his symptoms. He decided to go through with the surgery in February 2007.

"They laid it all out, that my head would be bolted to the table, that I would be awake for the whole thing," says Richardson, who lives in Douglasville. "My wife, Jennifer, was pretty stressed out. She stayed up all night doing laundry. I tried to get some sleep."

At 6 a.m. the morning of the surgery at Emory University Hospital, the operation started with a pre-op MRI as reference, and the frame being fitted over his head. "There was a shield above my head so there would be no contamination. Dr. Bob Gross and the other surgeons were on that side [performing the brain surgery] and Dr. DeLong was by my side, giving me commands, asking me questions, and mapping my responses."

In patients with dystonia, the leads are placed in the globus pallidus internus, the part of the basal ganglia that regulates voluntary movement.

During this phase of Richardson's surgery, the leads were placed in the correct spots inside his brain—the basal ganglia, specifically the globus pallidus internus (which regulates voluntary movement.)

Over four decades of discovery about the mysterious basal ganglia and its role in movement and movement disorders, DeLong has become a celebrated neurologist and researcher. Last year, he received the Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences (the "Oscar" of science) from a cluster of tech titans in Silicon Valley, including Mark Zuckerberg. He also received the Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award Award, among the most respected science prizes in the world, which he shared with Alim Louis Benabid of France.

At his acceptance speech for the Lasker in September, he said, "A growing fascination with how the brain controls behavior led me to medicine and then to neurology. This took a clear direction when I found a choice research position at the NIH in the laboratory of renowned researcher Edward Evarts. Because the other obvious brain regions were already assigned to other fellows, I was asked to work on the basal ganglia, a cluster of poorly understood brain structures, and to determine their role in the control of bodily movement."

This chance assignment evolved into promising treatments for Parkinson's disease, essential tremor, and dystonia, all of which emerge from the same motor network and are circuit disorders. "With deep brain stimulation, we're not curing or treating the disease, we're targeting the network," he says. "It's the circuit we're after."