When he was younger — before he had claimed art as a means of self-expression and survival — Fahamu Pecou invented a superhero, a cartoon character he named “Black Man.”

Pecou found refuge in sketching the edgy adventures of Black Man, the alter-ego of Ahmad, a brilliant young man whose father died while trying to develop a molecular transformer. Ahmad would build the transformer himself — morphing into a superhero with superhuman qualities.

Back in Hartsville, South Carolina, where Pecou sold his comic strip for 50 cents an installment, high school friends observed that Ahmad looked suspiciously like the boy who had created him.

They were right.

“The character was based on me and the things I aspired to, that I hoped for,” acknowledges Pecou, an Atlanta-based visual and performing artist now pursuing doctoral studies at Emory’s Graduate Institute for the Liberal Arts (ILA), whose critically acclaimed work has been exhibited in galleries from Paris to Panama, Switzerland to South Africa.

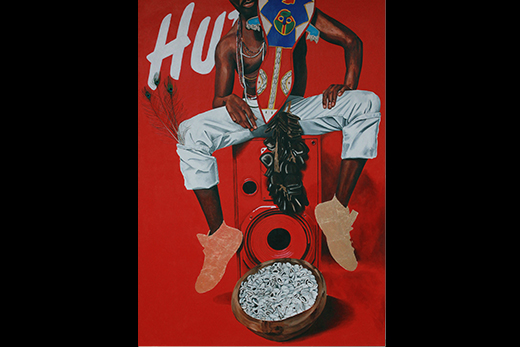

Even now, Pecou uses himself as a model, not in an autobiographical sense, he explains, but as an allegory, capturing traits “typically associated with black men in hip-hop and juxtaposing them within a fine art context … both the realities and fantasies projected from and onto black male bodies.”

This month, Pecou has a much-anticipated collaborative project set to go on display at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, on the heels of his first solo museum exhibit showcasing some of his largest works to date — by all measures, an artist on the ascent.

For Pecou, the journey — from a boy who once seized upon art as a refuge to a celebrated international artist noted for the shrewd cultural commentary that infuses his work — has been a jagged odyssey, indeed.

The Black Walt Disney

This winter, Pecou’s unique vision was showcased in the solo show “GRAV•I•TY,” on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia (MOCA-GA), which concluded Feb. 14.

The exhibit explored issues imbued in the controversial trend of “saggin” — a low-riding style of wearing pants that puts boxer shorts on full display — and built upon his broader research into contemporary representations of black masculinity in popular culture. Pecou contends that fashion trends such as “saggin” can be a politicized statement, “a demand to be recognized in a world that wishes to render you invisible.”

He knows what that feels like.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Pecou was only four years old the night that his father, who had long battled schizophrenia, murdered his mother as he and his young siblings watched television in a nearby room.

Pecou and his siblings were eventually sent to South Carolina to live in a public housing project with his mother’s aunt, a stern woman who had little patience for a sensitive boy who liked to sketch the cartoons he saw on television.

And so it was that Pecou invented Black Man — a super-human boy who stood strong against his enemies.

“Art was my saving grace, my go-to place when things got a little rough,” he recalls. “Despite the turmoil of our house, you would find me in a corner, with paper and pencil, drawing quietly.”

“I told my friends that I was going to be the Black Walt Disney,” Pecou says.

“Life After Death”

During his freshman year at Atlanta College of Art, a friend introduced Pecou to the High Museum of Art, the first time he’d ever entered a museum or gallery.

“It blew my mind — I saw a different potential for myself as an artist,” he explains. “I ultimately changed my major from animation to painting. There was something about it that made me feel more alive.”

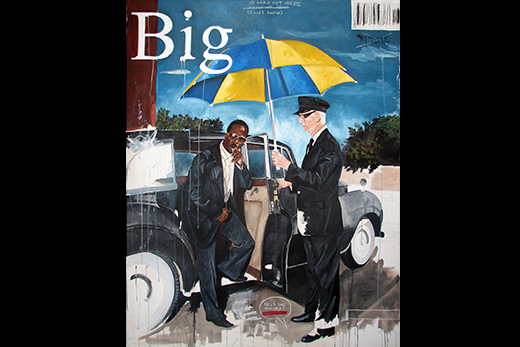

In time, Pecou was painting his cartoon characters, imposing his superheroes onto the covers of popular magazines. While taking a class at Spelman College, his work caught the eye of Arturo Lindsay, an artist-scholar known for ethnographic research on African aesthetics in contemporary American culture, who christened Pecou’s work “Neo-Pop.”

One night, a fellow art student stopped by Pecou’s room with a wooden box salvaged from a construction site. Pecou transformed the battered cement mold into a spirit box, “a tribute to my mom.” Inspired, he interviewed his siblings; from those excavated memories he would create his senior project, “Life After Death” — artwork that laid bare his own turbulent past.

“From that point on, I decided never to make art for the sake of making a pretty picture, but to move people and change the world,” he says.

From boyhood to manhood

Still, the years that followed were a creative struggle.

Following graduation in 1997, Pecou “lied his way into a graphic design job” in New York, working with rising performers, nightclubs and restaurants. Noting how different rappers often were from the personas they projected, he wondered: Why doesn’t someone market a visual artist the way we do a rapper?

The question drew him back to Atlanta, where he joined a friend to create a new design firm, and tried to get his own artwork into galleries, with little success.

So the young artist decided to create a brash, tongue-in-cheek underground campaign: “Fahamu Pecou is The Sh--t.” It was a subversive experiment, a parody of a promotional campaign “with no rhyme or reason,” Pecou admits. “And it was a hit.”

It also kindled his creative juices, fueling a series of paintings that played on the “NEOPOP” themes of celebrity, hip-hop and culture.

Then, a break. In 2004, Pecou was invited to join “Art, Beats and Lyrics,” a group show at the High Museum of Art. Interest in his paintings began to take off. Over the next few years, Pecou’s work would be featured in more than a dozen group shows or exhibits. Paintings he’d once struggled to sell were fetching thousands of dollars. Interest in his bold, urban work and challenging viewpoint was spreading.

But it was the birth of his children, daughter Oji and son Ngozi, that would bring him to a deeper, more introspective place.

“I began to think about my own journey from boyhood to manhood — not having a father around had affected me,” he explains. “I wanted to use my work to have a broader conversation with young black men about their identity, their masculinity, some of the inherited and imposed expectations that young black men face.”

The artist as scholar

It’s a focus reflected in Pecou’s work at Emory, where he’s now in his third year of graduate studies at the ILA and Laney Graduate School, drawn by “a deep yearning to be challenged in an intellectual environment.”

As Pecou searched for the right program, Michael Leo Owens, an associate professor of political science and friend, had suggested the interdisciplinary flexibility offered through Emory’s ILA would be a good fit.

What Pecou's art invites, Owens says, “is a really nice, long conversation and critique about not only black culture, but American culture, along with the potential to help young black men — and women — to believe there is a greater, broader set of opportunities available to them. He wants to see young black excellence.”

Pecou appreciates what he has found at Emory, where his scholarship and artistry intersect. For example, Pecou was able to expand upon themes from his “GRAV•I•TY” exhibit to write a research paper that he will present at an international conference on “Black Portraiture(s) II: Imagining the Black Body and Re-staging Histories” in Italy later this spring.

Through his studies, Pecou has “been able to engage with a lot of leading theorists around black masculinity, hip-hop theory — all of these viewpoints coming together that have allowed me to really think through my own the ideas.”

“Not only do I feel much more confident developing ideas and theories, it’s freed my work,” he says. “I find that I can address some of the concerns and ideas I have academically, which amplifies my art.”