The results are in from the first comprehensive survey of Emory University's 72 start-up companies.

Todd Sherer, associate vice president for research and executive director of Emory's Office of Technology Transfer, says the survey, which was several years in the making, is the most complete report to date on Emory's start-ups and their economic and societal impact.

"We've found that our start-ups are very successful in a number of different metrics, from attracting funding, to getting products to market, to creating jobs in Atlanta and elsewhere," he says.

Emory still spins out three to six companies per year, says Sherer, and approximately 80 percent of its start-ups were created since 2000.

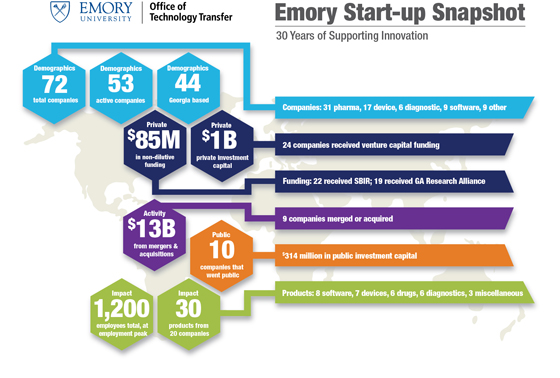

Of Emory's 72 start-ups:

- 10 (14 percent) went public

- 9 (13 percent) were merged or acquired

- 44 (61 percent) are based in Georgia

- 53 (74 percent) are still active

- 31 are in drug discovery/pharmaceuticals, 17 in medical devices, 6 in diagnostic technologies, 9 in software, and 9 in other fields

- 30 products went to market from 20 different companies

- 1,200 workers were employed, at peak

As far as funding, Emory start-ups received more than:

- $85 million in non-dilutive funding (requires no equity in return)

- $1 billion in private investment capital

- $314 million in public investment capital

- $13.5 billion from mergers & acquisitions

Universities are under increasing political pressure to assert, measure and improve their impact on national well being, with attention primarily on economic growth, job creation and competitiveness, found a Brookings Institute study last year about university start-ups. "Universities receive significant public resources for research and policymakers wish to hold them accountable for those investments," stated the report.

Policymakers also want universities to be more responsive to market forces and to be more entrepreneurial and more attuned to the needs of industry, the report found.

From discovering natural anti-tumor compounds, to developing new drugs to treat hepatitis C, tuberculosis, or Parkinson's disease, to creating safe and effective HIV vaccines, to inventing devices to improve heart surgery or lessen depression, Emory start-ups demonstrate daily the impact of academic research on our lives, says Sherer.

"Start-ups are a way to deploy early stage technologies that have not been able to be placed with an established company," he says. "And often the engagement of the faculty inventor as co-founder of the company ensures a more personal commitment."

That's why non-dilutive funding, which requires no equity in return, is so critical to small start-ups, Sherer says. "It's a way for these small companies to advance, to get to the point where private capital will be invested so the product can be generated and taken to market."

One perception has been that conflict of interest rules for academics are so restrictive that faculty inventions and university start-ups can no longer be successful, Sherer adds. "This report shows that's just not true," he says. "The emphasis has moved toward government agencies wanting a return on their investments, and to being able to show the impact of those dollars. University start-ups are an efficient, effective way to get these promising innovations out there so the world can benefit from them."