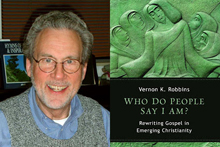

Vernon Robbins, who was appointed Winship Distinguished Research Professor in the Humanities at Emory in 2001, illustrates that point with his latest book "Who Do People Say That I Am? Rewriting Gospel in Emerging Christianity," (Eerdmans 2013) a product of his own dissatisfaction with the way early Christian writings outside the New Testament are often portrayed.

"I became unhappy with the way many of my colleagues primarily characterized gospels outside the New Testament in negative ways," says Robbins. "I came to see and believe that these gospels have a very close relationship to Matthew, Mark, Luke and John in the New Testament."

Those relationships, says Robbins, "were not being presented accurately and clearly to a broader reading public."

Robbins is familiar with the controversies within early Christian scholarship. The origins of his book go back to the beginning of his career studying with British-born American biblical scholar Norman Perrin at the University of Chicago Divinity School (Coincidentally, Perrin also taught at Emory's Candler School of Theology from 1959-64).

Then Robbins was asked by biblical scholar Robert Funk to be one of the founding members of the controversial Jesus Seminar, and the journey into controversy began. (The Jesus Seminar, a group of scholars who produced new translations of the New Testament and the Apocrypha and voted on their views on the veracity of Jesus' portrayals in scripture, caused quite an uproar in scholarly circles and beyond.)

Robbins, weary of the bitterness and controversy surrounding such scholarship, eventually withdrew from those discussions. But he never lost his conviction that there is much more to be learned from extracanonical early Christian writings.

"The gospels outside the New Testament are regularly building on Matthew, Mark, Luke or John, or some combination of them," he explains. Those relationships "were not being presented accurately and clearly to a broader reading public.

"I want to help people have the experience of reading a gospel outside the New Testament as a way of beginning to see things inside Matthew, Mark, Luke or John that they never saw before."

For instance, the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of Judas show Jesus as a severe critic of religious ritual. "So when you go back and carefully read the New Testament Gospel of Matthew, you begin to see there is significant criticism by Jesus of religious ritual."

The extracanonical gospels also regularly fill gaps in Matthew, Mark, Luke or John on important concepts such as the divinity of Jesus.

"When you read gospels outside the New Testament, you begin to see what a gospel would be written like if people really believed that Jesus is divine," says Robbins.

That could be a surprise for readers who presuppose that Matthew, Mark, Luke and John all present strong portrayals of Jesus as divine, he says. He lists early Christian writings such as the Gospel of Thomas, Infancy Thomas, the Gospel of Mary, and the Acts of John as presenting vivid and enlightening portraits of the divine Jesus.

In the second-century Acts of John, for example, which Robbins calls "an amazing document," John the Apostle relates what it was like to be with Jesus during his lifetime and presents Jesus as though he has a transfigured body . . . "so that Jesus was continually fading in and out of earthly/fleshly mode. It's fascinating."

As scholarship on early Christian writings outside the New Testament has grown and captured public imagination (witness Elaine Pagels' popular books on the Gnostic Gospels and Karen Kings’ book on the Gospel of Mary), Robbins has continued to write and teach with the conviction that the field is a rich resource, with much more to reveal.

"So if a person has been interested in these writings as I have, it now is possible to read through them, consult with scholars involved and present accurately these kinds of new understandings," says Robbins.

"This book is part of the writing of the new history of early Christianity that we really are now able to do in the 21st century."