In a National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded clinical trial, researchers at Emory have discovered that specific patterns of brain activity may indicate whether a depressed patient will or will not respond to treatment with medication or psychotherapy. The study was published June 12, 2013, in JAMA Psychiatry Online First.

The choice of medication versus psychotherapy is often based on the preference of the patient or clinician, rather than objective factors. On average, only 35-40 percent of patients get well with whatever treatment they start with.

"To be ill with depression any longer than necessary can be perilous," says Helen Mayberg, MD, principal investigator for the study and professor of psychiatry, neurology and radiology at Emory University School of Medicine. "This is a serious illness and the prolonged suffering resulting from an ineffective treatment can have serious medical, personal and social consequences. Our goal is not just to get patients well, but to get them well as fast as possible, using the treatment that is best for each individual."

Mayberg’s positron emission tomography (PET) studies over the years have given clues about what may be going on in the brain when people are depressed, and how different treatments affect brain activity.

These studies have also suggested that scan patterns prior to treatment might provide important clues as to which treatment to choose. In this study, the investigators used PET scans to measure brain glucose metabolism, an important index of brain functioning to test this hypothesis.

Participants in the trial were randomly assigned to receive a 12-week course of either the SSRI medication escitalopram or cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) after first undergoing a pretreatment PET scan.

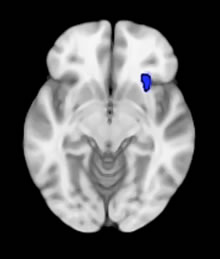

The team found that activity in one particular region of the brain, the anterior insula, could discriminate patients who recovered from those who were non-responders to the treatment assigned. Specifically, patients with low activity in the insula showed remission with CBT, but poor response to medication; patients with high activity in the insula did well with medication, and poorly with CBT.

| PET finding in the right anterior insula superimposed on the MRI for anatomical orientation. When activity in this region is low—the patients got better with CBT not drug. Source: Helen Mayberg |

"These data suggest that if you treat based on a patient’s brain type, you increase the chance of getting them into remission," says Mayberg.

Mayberg is quick to add that this approach needs to be replicated before it would be appropriate for routine treatment selection decisions for individual depressed patients. It is, however, a first step to better define different types of depression that can be used to select a specific treatment for a patient.

A treatment stratification approach is done routinely in the management of other medical conditions such as infections, cancer, and heart disease, notes Mayberg. "The study reported here provides important first results towards the development of brain-based treatment algorithms that match a patient to the treatment with the highest likelihood of success, while also avoiding those treatments that will be ineffective."

Mayberg is the Dorothy C. Fuqua Chair in Psychiatric Imaging and Therapeutics. First author on this study is Emory neuroscience graduate student, Callie McGrath. Co-investigators include Mary Kelley, PhD, research associate professor of biostatistics in the Emory Rollins School of Public Health, Boadie Dunlop, director of the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program, and W. Edward Craighead, J. Rex Fuqua Chair and a Vice-Chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine, and the Department of Psychology, Emory University