With her white lab coat and security badge, Heather Lin could easily pass for a physician as she glides through clinical rounds alongside pediatric neurologist Barbara Weissman.

But watch closely, and it's apparent that Lin is primarily observing and listening — of particular interest is the subtle, seamless way Weissman adjusts her communication style when speaking with both her tiniest patients and their anxious parents.

At 18, Lin is thrilled to have this proximity to the delicate doctor-patient dynamic, as well as exposure to real-world clinical neurology — a rare opportunity outside of medical school and an extraordinary glimpse into a future that she hopes to pursue.

For college undergraduates like Lin, the opportunity to interact with patients and work in partnership with physicians to diagnose and understand neurological disorders is virtually unprecedented.

But students enrolled in MD Summer Experience at Emory (MD-SEE) are finding that and more: clinical neurology experience, professional mentoring, classroom guidance, and a rigorous examination of real life medical issues and practices.

"I'm majoring in neuroscience, but couldn't decide if I wanted to take the research path or the medical path," says Lin, a rising junior at Brandeis University and MD-SEE student. "You can say that you want to be a doctor, but you don't know it until you really experience what they do."

"Here, you'll see a patient, walk out of their room, and the doctor immediately starts explaining their thought process — what they saw and heard, why they chose to do what they did," she explains. "You don't really find that in a textbook."

Med school preview

The idea behind the MD-SEE program arose from a Clinical Neurology Study course created by Paul Lennard, director of Emory's Neuroscience and Behavioral Biology (NBB) program and Neurology Professor Linton Hopkins more than decade ago — a course that's still so popular "there's usually a one- to-two year waiting list to get into it," Lennard confirms.

"We only take eight students each semester, and they're virtually all – with a few exceptions – NBB seniors, which means others interested in neurology at Emory, as well as students outside this university, had no option," he explains.

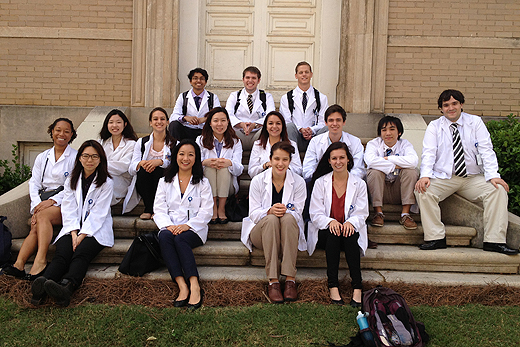

Genuine clinical experience is at the heart of the six-week MD-SEE summer program, jointly sponsored by the Emory College NBB program and Emory School of Medicine's Department of Neurology and now in its second year.

Already, the number of applicants and the quality of institutions they represent are growing, says Lennard, who helped found MD-SEE and has served as director of Emory's NBB undergraduate program since its inception in 1997.

This summer, he reports about 60 applicants were vying for 20 spots. About half of the class is from Emory, with other students coming from universities that include Vanderbilt, M.I.T. and the University of California, Berkeley.

Lennard acknowledges: "Our reputation is spreading."

"It's a medical school experience," he says. "They're learning how to do physical examinations, the basics of diagnostic techniques. They're learning to put together a case study of a patient, about patient privacy and medical ethics and patient-doctor interactions … experiencing the high points — and some of the very tragic low points — in medicine, and finding out if this is something that they really want to do."

Lennard knows of no other program that "offers this level of in-depth interaction with patients and physicians."

"These students tend to be the best of the very best and this tends to be an experience that changes their lives, that gives them the context and the motivation, and an understanding of medicine that they could not possibly have gotten from coursework," he says. "It is truly an internship."

Classrooms rooted in reality

Based in Emory College, the program links the University's popular NBB program — among the fastest-growing undergraduate majors on campus — and the School of Medicine. Co-director Jaffar Khan, an associate professor of neurology and award-winning clinician-educator, coordinates the medical component of the program.

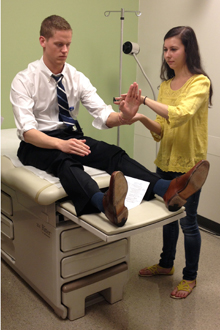

MD-SEE students practice performing neurologic exams and learn real-world diagnostic skills.

MD-SEE students are paired with a physician-mentor, whom they accompany on clinical rounds that may take them into a range of settings, from Grady Memorial Hospital and Emory Children's Center to Wesley Woods Hospital, Emory Midtown Hospital, Emory Clinic Sleep Center or other on-campus clinics.

"Students are not only exposed to fundamental basic science aspects of neurologic disease, but also get firsthand experience observing people living with neurologic disease," Khan notes.

"As a secondary outcome, (students) acquire knowledge about the patient-doctor relationship, the health care system, patient's rights, and a clinician's clinical skill set — history-taking, performing an neurologic examination, developing a differential diagnosis, and diagnostic testing," he adds.

Afternoon classes feature presentations from top Emory physicians and researchers. Once a week, lectures focus on professional skills, such as exams and diagnostics.

Two days a week, students practice presenting case studies focusing on the conditions of patients whom they've actually met through clinical rounds — preparation for a final presentation on a patient and neurologic disorder that most interests them.

On Fridays, the class tours medical-specific sites, such as Emory's new fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) facility. Even a weekly "movie night" turns into a teachable moment; the movie "Awakenings" features a discussion led by neurologist Michael Silver.

Overall, the program provides a "firsthand look at careers in medicine," informing students about the medical field, academic environment and research through discussion groups with clinical and research faculty, Khan notes.

"Most of these students are contemplating applying to medical school or other professional schools in health care," he says. "This course affords them the opportunity to ‘test the waters' before making a final decision."

Real-world teaching tools

Parkinson's Disease. Epilepsy. Alzheimer's Disease. Cerebral Palsy. In the MD-SEE classroom, these are not only the stuff of daily conversations but also real-world teaching tools.

On a recent afternoon, MD-SEE student Scott Piraino presents a case study on a 52-year-old male who had suffered an apparent stroke while working out.

"Right side facial droop, fluctuating mental status, ischemia of the brain stem…" Piraino reports, as he begins a discussion of the clot-busting drug t-PA, as well as advances in therapeutic hypothermia, which stretches a critical window for stroke treatment by lowering the body temperature.

Observing Piraino's PowerPoint presentation, Khan and Lennard are poised with targeted feedback.

"You know, researchers at Emory have started looking at the use of progesterone in treating traumatic brain injury," Lennard observes. "Know your audience. If you're speaking at a university, check to see what kind of research they're doing."

Khan concurs: "Don't be afraid to brag a little bit. At Emory, you are seeing things that are not a part of standard care or being done any place else."

For Piraino, who attends American University, the critique is all part of the MD-SEE experience: "Immersion is a good way to describe it," he says, smiling.

"The neuroscience part of this is really interesting — and the faculty is great — but my main interest in the program was the chance to shadow physicians. I'm just grateful for that opportunity."

That access has been an education in itself, agrees Shahdabul Faraz, who is majoring in biology at Emory.

"I've had informal opportunities to observe physicians in the past," he says, "But I wasn't sure what they were actually doing. Now, I have the academic context to understand what's really going on."