Matthew Pierce is using his expertise in urban planning to create a window on the worship life of Atlanta that otherwise might be lost to the ages.

Pierce, a rising fourth year Ph.D. student in Emory's Graduate Division of Religion, is taking a very specific approach to the study of liturgical history by focusing on the interaction between the worship life of communities in early 20th century Atlanta and the practices of their surrounding cultures, even if those communities have changed or disappeared.

In order to get a "read on a place," urban and regional planners rely on a plethora of data to chart all kinds of demographic, economic, transportation and other trends, says Pierce. To conduct informed assessments on a place, he adds, someone first must undertake the painstaking work of "mapping" the landscape.

Atlanta Mapping Project

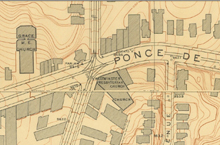

For the past two years, Pierce has been doing precisely that: entering data for the Atlanta Mapping Project. The project draws from a series of maps of Atlanta in 1928 in order to spatially digitize as much known information as possible.

Along with a team of volunteers and other students, Pierce has helped render every benchmark, every manhole cover, every building footprint to render a digital map of historic Atlanta. When comparing Pierce's retrofitted map with that of the Atlanta Regional Commission from 2008, researchers are able to see where neighborhoods have been lost and shaped, for example, among a number of other differences.

Once the "details" of the maps have been digitized ("drawn"), those spatial features can be linked with other data—information from the census, for example, the City Directory (pre-cursor to the phone book), or church records. This new set of tools will allow researchers and others to "search" for individuals and businesses in Atlanta in 1928 much the same way individuals might, say, search for individuals and businesses today by performing a Google search or by inputting an address into a GPS device like those made by Garmin and TomTom.

To illustrate, let's say that Mr. Smith lived at 100 Edgewood Avenue in 1928. We also know that Mr. Smith worked at the Candy factory on Memorial Drive and that he earned $100 a pay period, and was a member of Park Avenue Baptist Church in Grant Park. From this information we can digitally recreate Mr. Smith's life in terms of racial demographics (because city directories from this time would indicate if one was "colored" or "non-colored"), transportation patterns, religious affiliation and much more.

Liturgical Maps

This is where Pierce brought his training as a liturgical scholar to the fore in his work on the mapping project. "I was interested in the way in which churches—but religious communities in general—might begin to think more broadly about the way they influence urban policy and the way in which the shape of the landscape affects them," he says. Pierce set out to map the liturgical landscape of 1920s Atlanta using information from church directories, which provided a nuanced way of investigating the environmental factors that impact congregational formation.

For instance, Pierce has noted the various modes of transportation that might influence congregational size, but he has also begun to identify certain "semiotic boundaries" at play. Such boundaries are not those which present physical obstacles, but rather those which separate neighborhoods (the phrase "wrong side of the tracks" points to the way railroad tracks can serve as such semiotic boundaries).

Pierce has also been able to map what he labels "congregational watersheds"—the area from which a congregation draws its membership. These are geographical and topographical features that impact congregational formation. Just as watersheds influence settlement and transportation patterns, so too do these factors impact congregational life.

Supporting Clergy

When asked about the payoff for the countless hours of data entry, research and geocoding that he has done for this project, Pierce's eyes brighten. By highlighting socio-cultural factors that influence congregational formation, Pierce has developed a tool for measuring how economic, racial, denominational and liturgical features of congregational life intersect at a particular place and time. Pierce puts it simply: "The end game is to at least problematize, [the assumption] 'this is just how things are.'"

A United Methodist, Pierce seeks a way of supporting Methodist pastors who are relocated every couple of years to serve different congregations. "They enter congregations and neighborhoods not of their own making," observes Pierce. "How does one faithfully engage the larger community of which each congregation is a part?" Pierce's scholarship promises new answers to this perennial question.

Written by Jacob D. Myers, a fifth-year doctoral student in Emory's Graduate Division of Religion.