For many American churchgoers in the 19th century, the Sunday sermon functioned as the equivalent of "breaking news."

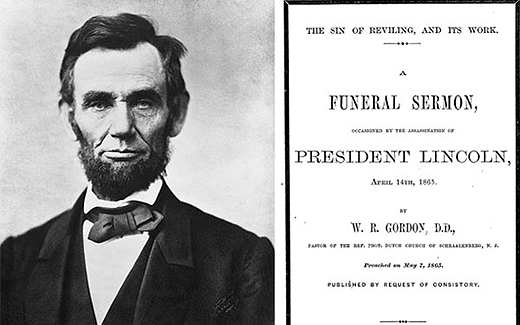

After Abraham Lincoln was shot on Good Friday, April 14, 1865, dying some nine hours later, ministers were among the first to provide commentary on the passing of the president and the state of the nation.

In those days, sermons were also a popular publishing genre, says Pat Graham, director of Emory's Pitts Theology Library. Texts of significant sermons were published as pamphlets, and thousands were circulated—an early version of religious mass media.

Sermons go digital

Fast forward to the 21st century. In late 1999, Pitts Library, part of Candler School of Theology, acquired the full text of 57 sermons (some 1672 pages and 481,575 words) published across the country in the weeks following Lincoln's assassination.

To protect the fragile documents, Pitts partnered with the Emory Libraries Preservation Office and Beck Center to digitize and create a website for the sermons. OCR and SGML markup were applied to create searchable files that enabled researchers to do textual comparisons of the sermons that would be difficult otherwise.

As it turns out, the Lincoln sermons were on the leading edge of the now massive and ever-growing wave of digital collections inspiring digital-based scholarship.

"The quality of OCR software is much better now than it was even 10 years ago," says Graham. He adds that today's data analysis tools now make it possible to "start asking questions you couldn't ask before and start doing things you couldn't do before."

Pushing the digital envelope

Recently a group of Emory graduate students, fellows in Emory's Digital Scholarship Commons (DiSC), decided to use the Lincoln sermon collection to do just that.

"We've been mulling over the question of whether the push to 'go digital' with a project is always a good thing," explains Sarita Alami, a DiSC fellow and part of the project team.

"We were curious to see what we'd find if we used a bunch of digital texts analysis programs, and then we simply read the texts. Would the digital program offer new insights and save us time?" she asks. "Or would they clutter up an otherwise straightforward textual analysis?"

The DiSC fellows set up their own website, "Lincoln Logarithms," using the Lincoln sermons as "a game piece for creating a guide for people who are interested in doing digital projects and don't know what tool to use or where to turn," says Alami. "We created an online map so that researchers can know what to try."

The team tested four free, open-source digital text tools—MALLET, Voyant, Paper Machines and Viewshare—and set to work.

The results

The findings tended to lead to more questions, which is a good thing, says Alami.

For instance, using the text analysis tool Paper Machines, the team created a word cloud showing that even though the majority of sermons were from the Northeast, the words "slave" and "slavery" were not prominent, while "the overall prevalence of the word 'government' appears deserving of further investigation."

"Doing digital research can be very experimental—sometimes it takes a lot of tries before you find something that's going to give you results that are interesting," says Alami. "That in itself was a finding," she adds.

Alami says the goal of the Lincoln sermons project was to create a kind of digital research tool guide that will help researchers choose the most effective digital tools for their work by answering a series of questions.

"Say you have a body of text – is it digitized? Is it more than 500 documents? Does it cover a variety of geographic locations? Does it stretch across a few days or a number of decades? Depending on how they answer the questions, we can suggest different tools that would be helpful for them," Alami says. "Nothing like this exists right now."

What's in the sermons?

In addition to digitally analyzing the sermons, Alami and the research team also attempted to read them all—no one finished.

But according to Graham, the sermons are as fascinating as they are varied. "One [sermon] was preached by a Unitarian missionary from Boston in South Carolina," he says. "There's also a sermon done by a woman, an extemporaneous address for a group of 3,000 in New York City."