Professor Anna Grimshaw of Emory's Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts (ILA) is an anthropologist and ethnographic filmmaker. On March 29, the first of her four-part documentary "Mr. Coperthwaite: A Life in the Maine Woods, Part 1. Spring in Dickinson's Reach" was shown at the Atlanta Contemporary Arts Center to a full house. The film's subject is William Coperthwaite, a Harvard graduate who has lived alone on some 500 acres in the Maine woods for five decades in a yurt, practicing a self-sustaining life, although visitors and apprentices come and go.

Grimshaw spoke with Emory Report about her discipline, the documentary, and nontraditional scholarship at Emory:

How did you come to know Bill Coperthwaite?

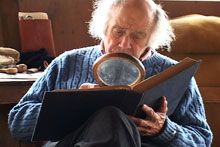

Bill Coperthwaite

I bought a house in Maine and kept hearing about a man who lived in the woods, so my partner and I walked out there a couple of times—it's a wonderful walk through the forest—to get to his place before we found him at home. He is happy to engage in conversation with people who have walked a mile and a half to see him. He lives in a three-story yurt, and there are all these smaller yurts: a boathouse, a kitchen, a john, a library.

What was he like when you did meet him?

He's an interesting mixture, a man who has lived alone in the woods for 50 years but who is also social, with both a passion for tools and a love of poetry. He enjoys solitude, but always has a project, something to do. He enjoys testing things out—what might happen if I do this with these tools and these materials? I have video of him designing a new wheelbarrow to make it more balanced. He is always looking for ways to do things more efficiently. He's from Maine originally, from a traditional family, and has a PhD from Harvard, but for his dissertation he didn't write a text, he created a traveling Inuit museum, teaching about Inuit tools that were no longer used.

Part of your own work and teaching involves nontraditional scholarship. Has the ILA been a good home for this kind of endeavor?

Yes, of course, I've had students who have incorporated performances, photography, dance, film, and painting as part of their scholarly inquiry. We in the ILA try to think coherently and critically about how these different forms can be brought into productive relationship. We are interested in experimental works, not just in content but form. One of the things to emerge from my own particular concerns was the founding of the Emory Visual Scholarship Initiative (a student-run organization committed to visual and multimedia practices in contemporary interdisciplinary scholarship). And I encourage students to include nontraditional sections in their dissertations, which of course provokes a lot of anxiety and discussion.

Did any of the graduate students take you up on it?

One of my students included a series of short films as a chapter in her dissertation. Another is including performance. It's all part of testing the waters. That's the challenge—to make people open to new forms of scholarship, to convince their professors and peers to take it seriously, and not be dismissed. I mean, it raises interesting questions—who defines convention? These are conventions, after all, nothing more than that. What forms of knowledge and scholarship are legitimized, and by whom? Many of my students' backgrounds are in performance, art, music. We are at a place where they can explore that.

A review of your documentary said you had "as unobtrusive a camera as you'll find almost anywhere." Can you talk about the process of filming and what you are trying to do with the camera?

This is not a documentary that tries to explain, but one that asks the viewer to enter an imaginative world that puts them in relationship with Bill. I don't try for objectivity, I try to get as close as possible to the subject, to be responsive and capture the unfolding of his life. I don't have a script, I don't ask questions, I just wait to see what happens. I tell students, you are using the camera as a form of inquiry, to find something out.

How did you decide on the documentary's title, "Mr. Coperthwaite: A Life in the Maine Woods"?

He does have a fabulous name, doesn't he? Straight out of Dickens. He lives in homage to Thoreau, Emerson, Emily Dickinson, and his land, which he paid something like $500 in the 1960s, is actually named Dickinson's Reach.

Why break the film into the four seasons?

When I committed myself to documenting Bill's life for a year, I knew I would capture all four seasons, but I imagined it as a single film. Once I started editing, though, I realized I couldn't do that, it would take away from the time in the moment. The first film, spring, is the longest; I probably shot 33 hours of video for every hour of the film. The other three films are less than an hour, so it's 4.5 hours total.

What has been the reception to "Mr. Coperthwaite"?

It has been well received, especially at its international screenings. I have been entering it in ethnographic film festivals and it has shown in Moscow, Vienna, Estonia, and Ljubljana. People elsewhere tend to think of America as an industrialized, capitalist world, and they've told me this has given them a different perspective.