"Afterward, when the world was exploding around him, he felt annoyed with himself for having forgotten the name of the BBC reporter who told him that his old life was over and a new, darker existence was about to begin.

"She called him at home, on his private line, without explaining how she got the number. 'How does it feel,' she asked him, 'to know that you've just been sentenced to death by the Ayatollah Khomeini?'"

–Salman Rushdie, "Joseph Anton: A Memoir"

And so it began for Salman Rushdie — the earliest moments of an ordeal that would capture international headlines, stir public debate and shape his personal and writing life for nearly a decade.

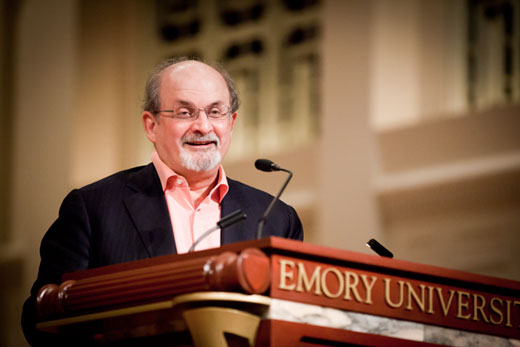

Rushdie recalled his impressions of that morning, which abruptly shifted from conventional to life-changing with the news that he'd been targeted for death by the Ayatollah Khomeini, during a reading from his new autobiography, "Joseph Anton: A Memoir," before a capacity crowd Sunday, Nov. 4 at Glenn Memorial Auditorium.

It was Feb. 14, 1989, when the spiritual leader of Iran proclaimed Rushdie the target of a fatwa for penning "The Satanic Verses," a novel the cleric deemed blasphemous; all "zealous Muslims" were urged to execute the author.

His new memoir marks the first time Rushdie has written at length about his experiences living under that death threat.

Narrated in the third-person — a key to helping the acclaimed novelist tell his story, he said — his 11th book explores the weight of a life in hiding under round-the-clock police protection, the healing power of relationships, and the battle for free speech.

MARBL and the memoir

A University Distinguished Professor at Emory, Rushdie opened the evening by acknowledging the role having his archives organized and housed at Emory's Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library (MARBL) played in helping him assemble the memoir.

"I think it's quite clear to me had it not been for the work that was done here, I would have never been able to write the book," recalled Rushdie, whose papers had previously been stuffed in about "150 cardboard boxes I made no attempt to organize."

Without appearing "to be the least bit alarmed with this," Emory spent years organizing it, he explained.

"Eventually, I found myself in a position with my entire life neatly catalogued," he said. "That's one of the moments when I thought, ‘Now, I actually could write this book.' "

Writing an autobiography was not something Rushdie had ever aspired to attempt. "I thought it was the most tedious form," he acknowledged. "I became a writer to make things up and write about people who are not me. Then I acquired the curse of an interesting life."

In some ways, a memoir was inevitable. "Writing is a sort of disease," Rushdie explained. "Even when a writer is going through a part of his life which is not at all pleasant, there is a bit of him … whispering in his ear saying, 'good story' The worse it is, the better it is. I knew there was this story to tell. I used to joke to my friends it was my old age pension."

A disjointed decade

Reading from his memoir, Rushdie described the day he learned of Khomeini's threat as bewildering. After a reporter's phone call, he "moved nervously around the house, drawing curtains, checking window bolts, his body galvanized by the news."

But when a car arrived to take him to a previously scheduled television interview, he didn't think twice about keeping the commitment. Although he did not know it at the time, he would not return to that house for three years.

Immediately, there were concerns for the safety of his family: a mother and younger sister, still in Pakistan, two other sisters scattered about, a nine-year-old son with the boy's mother.

The next day, a British intelligence officer came to see Rushdie. The threat against him was serious; he was entitled to the protection of the British state. They asked him to choose a pseudonym, advising against an Indian name.

"I thought I would go to literature, my other country," Rushdie explained, choosing "Joseph Anton" as a nod to authors "Joseph Conrad" and "Anton Checkov."

Thus began a long-running relationship with Britain's Scotland Yard's Special Branch and the beginning of a life strangely disjointed, at times both harrowing and comical, Rushdie said.

"Nobody thought it would last very long," he recalled. "It ended up being more than a decade."

Humor amidst the fear

With wry humor, Rushdie recounted the many absurdities of his new life.

Once, while watching a British Muslim leader interviewed on TV, he heard the interviewer ask the soft-spoken older man if he'd actually read "The Satanic Verses."

No, of course not, he replied. It was evil.

"Have you read any of Mr. Rushdie's books," the interviewer asked.

Lifting his shoulders in a half-hearted gesture, the man explained: "You know, books are not my thing…"

"If it wasn't for the fact that this wasn't funny at all, it would have been very funny," Rushdie recalled.

Rushdie also found himself learning about the unique humor of his protectors. When he asked why one of his drivers was called "The King of Spain," he learned that it was because he'd had a police car — a Jaguar — stolen from him while on duty.

"The King of Spain — Juan Car-loss," Rushdie explained.

Yet, through all the years of varying threat levels and meetings with top British intelligence officials, the closest Rushdie actually came to being killed was in a car accident in Australia. The car he was driving bounced off a truck hauling — ironically — fertilizer.

In closing, Rushdie acknowledged the power of friendship in helping him through those years, from the support of personal friends to London's literati and his police protectors.

"This conflict was a big battle between love and hatred," he said. "In the end, I think the reason I'm here is that love proved to be stronger than the hate."