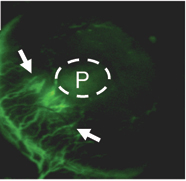

Blood vessels are attracted toward a cell pellet (P).

Scientists have discovered that ARF, known to act inside the cell, can also inhibit the ability of a tumor to attract new blood vessels.

Researchers at Winship Cancer Institute have identified a new function for a gene that normally prevents the development of cancer.

Scientists had known that the gene, which encodes a protein called p14 ARF, works inside the cell to control proliferation and division. A team led by Erwin Van Meir, PhD, discovered that p14 ARF also regulates tumor-induced angiogenesis, the process by which growing cancers attract new blood vessels.

The findings, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, provide insight into how cancers form and progress, communicate with surrounding vascular cells and could guide the development of new therapies to fight tumors whose growth is driven by loss of p14 ARF.

Van Meir is professor of neurosurgery and hematology & medical oncology at Emory University School of Medicine, and director of the Laboratory for Molecular Neuro-Oncology at Winship Cancer Institute. Abdessamad Zerrouqi, PhD, research associate, is the first author of the paper.

Pinning down the new function for p14 ARF was a several-year detective investigation for Zerrouqi. The gene was a slippery target because growing cells in culture tend to lose or silence it, he says. P14 ARF is not turned on in most tissues of the body, but is activated in response to aberrant growth signals.

The gene encoding p14 ARF is mutated or silenced in many types of cancers, including most gliomas, the most common brain cancer in adults. People who inherit mutations affecting this gene develop “melanoma-astrocytoma syndrome,” with increased occurrence of both types of tumors. ARF stands for “alternate reading frame” because the DNA sequence overlaps with another protein that is read out of step in comparison to ARF. Previous research had linked the function of p14 ARF to another gene, p53, which is also frequently mutated in cancers. P53 is known as “guardian of the genome” because it shuts down cell division in response to DNA damage.

Zerrouqi says several clues pointed to a separate function for p14 ARF. P14 ARF is often lost when astrocytoma progresses to glioblastoma, a more deadly form of brain cancer.

“These tumors are bigger, more infiltrative and more vascularized,” he says. “Yet p53 is usually lost at an early stage, before this transition takes place. This suggested that p14 ARF has a function that is independent of p53.”

Zerrouqi could show that restoring p14 ARF in cells from a tumor that had lost it interfered with the tumor’s ability to stimulate blood vessel growth. P14 ARF induces brain cancer cells to secrete a protein called TIMP3, which inhibits vascular cell migration, he found.

Zerrouqi and Van Meir’s findings are applicable to brain cancers as well as several other cancer types. TIMP3 itself has been found to be silenced in brain, kidney, colon, breast and lung cancers, suggesting that it is an obstacle to their growth.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation of the US, the American Brain Tumor Association, and the Southeastern Brain Tumor Foundation.

Zerrouqi, postdoc Beata Pyrzynska and Van Meir collaborated with Maria Febbraio, PhD, a researcher at the Cleveland Clinic to probe angiogenesis and Daniel J. Brat, MD, PhD, Emory professor of pathology and laboratory medicine, for pathological expertise.

Reference: A. Zerrouqi, B. Pyrzynska, M. Febbraio, D.J. Brat and E.G Van Meir. P14ARF inhibits human glioblastoma–induced angiogenesis by upregulating the expression of TIMP3 J. Clin. Invest (2012).

Writer: Quinn Eastman