To make it possible for cancer immunotherapy to help more people, think small. Small molecules, that is.

A major class of cancer immunotherapy agents, known as checkpoint inhibitors, revive the activity of immune cells that cancer cells have lulled to sleep. Generally, these agents are antibodies: highly specific, yet bulky proteins that do not easily diffuse through the body.

If scientists want to boost immune cells' ability to kill cancer cells, then plenty of other tools - vast libraries of more traditional "small molecules"-- are potentially available. What they need is a way to sort through them, a platform for screening thousands of drugs.

This is what Emory researchers report in a new Cell Chemical Biologypaper. They also demonstrate that a class of drugs called IAP antagonists, one of which is already in clinical trials, can promote immune activity against cancer cells in their system.

Although checkpoint inhibitors are now FDA-approved for several types of cancer, many patients do not benefit from them. Finding drugs that loosen other parts of the immune response could increase efficacy, especially for types of cancer against which checkpoint inhibitors are ineffective by themselves.

Lead author Haian Fu, PhD, chair of the Department of Pharmacology and Chemical Biology at Emory University School of Medicine, says that drug discovery efforts in cancer immunotherapy have mostly focused on regulatory molecules on the outside of cells, which antibodies can easily reach.

"This is a robust co-culture system that enables high throughput screening for cancer immunotherapy," says Fu, who is also leader of Winship Cancer Institute's Discovery & Developmental Therapeutics Program. "There are many targets inside the cell. We want to shine a light on those intracellular targets."

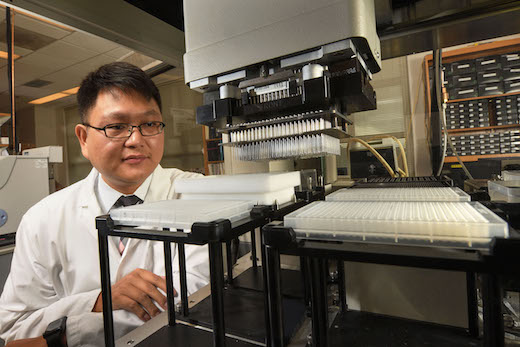

Working with Fu, instructor Xiulei Mo, PhD and colleagues created a system that can test whether compounds enhance the ability of human immune cells to suppress cancer cell growth. They call it HTiP, for "High-Throughput Immunomodulator Phenotypic Screening Platform."

The HTiP system uses a mixture of human immune cells, combined with cancer cells carrying a known growth-driving mutation. The Emory researchers began with the well-known oncogene KRAS, and compared the effect of cancer cells (colon and lung cancer cell lines) with and without the KRAS mutation. The presence of the KRAS mutation was immunosuppressive, meaning that in the Emory system, the KRAS mutation provides resistance against immune cells killing the cancer cells.

Mo screened a library of about 2,000 known compounds, isolating the drug birinapant. It enhanced immune cell activity against the cancer cells, while doing little to the cancer cells on its own. Birinapant is part of a class of drugs called IAP antagonists, which are already being studied for anticancer activity.

"This was strong evidence for their relevance as immune enhancers," Fu says. "It was a timely validation of our system."

In fact, birinapant is being tested in combination with a checkpoint inhibitor. Two other IAP antagonists had similar effects in the same system, the researchers found.

The screening platform is agnostic to the mechanism of KRAS immunosuppression, or the precise type of immune cell. Fu notes that most checkpoint inhibitors appear to act on cytotoxic T cells, but the screening platform uses a combination of immune cell types.

"The effect in our system could come from any or all of those cell types," he says. "Adaptive or innate response."

All that is needed is for a compound to reverse the effect of the KRAS mutation. The system could be easily modified to test the effects of other oncogenic mutations, or to focus on one particular type of tumor antigen-specific immune cells, he says. The team also plans to expand its screening efforts, since 2,000 compounds is actually small, compared to the number of potential drugs.

Co-authors include Cong Tang, Qiankun Niu, PhD, undergraduate Tingxuan Ma and Yuhong Du, PhD. Du is associate professor of pharmacology and chemical biology at Emory University School of Medicine and associate director for assay development and high-throughput screening at the Emory Chemical Biology Discovery Center. Tang is a student in the Emory University--Xi'an Jiaotong University Health Science Center exchange program.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (U01CA217875, U01CA199241, P30CA138292) the Georgia Cancer Coalition/Georgia Research Alliance and the Emory Chemical Biology Discovery Center.