It's late summer and a breeze drifts across the restaurant patio, where diners are clustered around long tables in bright green chairs that match the park-like setting. As the group looks over the dinner menu, neurologist Gregory Esper cautions everyone to make their selections carefully.

“There are foods and drinks that can induce migraines,” says Esper, director of general neurology and neuromuscular diseases at Emory Clinic and associate professor at Emory School of Medicine. “The most common are processed meats, aged cheeses, and red wine. But you might be sensitive to a particular food not on the ‘list.’ I know one woman who would get a migraine if she had the artificial sweetener stevia. Aspartame in diet drinks can be a trigger as well.”

Beyond migraines being a clinical interest, Esper himself suffers from them, as do each of the five guests, who've come together for a "Dinner with a Doctor" event organized by Emory Medicine magazine. This is an opportunity to discuss migraine symptoms, triggers, treatments, and medications with an expert over a casual dinner. While Esper can’t offer specific suggestions in this situation, he can discuss generalities and answer questions broadly. “So, what constitutes a migraine as opposed to a headache?” Esper asks. “Well, it should be throbbing in nature, at least moderately intense, and usually only on one side. In fact, the word is French for ‘pain in one half of the head.’ ”

Migraines can last from hours to days—most last 4 to 72 hours without treatment—and are sporadic. “If someone has a headache every day, that signals that it is not just a migraine,” says Esper. “Something else is going on.” In about 10 percent of cases of migraine-like headaches, the root cause is something else—a secondary condition.

The majority of migraine sufferers—60 percent to 80 percent—experience “common migraines,” in which the main symptom is the pain itself. “Classical migraines,” which include auras or other visual or sensory changes, can feel dangerous but usually are not, says Esper. “You might wonder if you’re having a stroke,” he says, “but a stroke is associated with a headache in only about 8 percent of cases.”

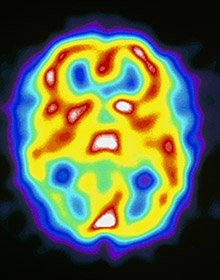

This single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan captures a patient’s brain during a migraine attack. The horizontal brain scan indicates high brain activity in red and yellow and low activity in green and blue.

This single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan captures a patient’s brain during a migraine attack. The horizontal brain scan indicates high brain activity in red and yellow and low activity in green and blue.

The thinking is that, due to a stimulus and genetics, deep structures in the brain trigger activation of the “trigeminovascular system.” This causes blood vessels to dilate along the covering of the brain—the meninges—which is a very sensitive structure. Inflammatory mediators and neurotransmitters then seep onto the surface of the meninges, further dilating blood vessels and making them more “leaky.” These mediators and neurotransmitters excite the trigeminal nerve—the largest and most complex of the cranial nerves, responsible for sensation in the face and head—which stimulates the meninges to send signals to the part of the brain that senses pain.

“It becomes a vicious cycle,” Esper says, “which is why the pain can last a long time unless we cut it off with medications.”

When migraines start at a young age and are not treated correctly, they can change brain physiology. For some, migraines start at puberty and peak in middle age.

Others have experienced migraines since early childhood. For still others, migraines come on later in life, or after an event or injury.

One participant says his first migraine occurred after he fell in the night due to a spell of vertigo, and that he experienced a visual shift as well.

Sometimes, the participants say, they see flashing lights or feel strange before the headache’s onset—numb, tingly, or overly sensitive to stimuli.

“I don’t see auras, but sometimes I smell roses,” says one.

“Are there migraine-sniffing animals?” asks another. “My dog will come up to me and smell my eyeball and within an hour or two, I’ll have a migraine.”

“I don’t know about that,” says Esper, smiling, “but visual or sensory changes, and nausea or

Most migraines involve a pulsing type of pain, which can migrate, says Esper. “Mine

“Mine feel like there’s an ice pick in my head,” says one participant. “Pain was just something I thought was normal.”

Preventing a migraine is far superior to trying to get rid of one that is

“In the past 10 years, I have had tension-type headaches that, if controlled quickly with Fioricet, will go away,” says a participant who has had lifelong migraines. “If not, they will morph into a migraine in less than an hour.”

In general, Esper says, migraine pain is caused by vasodilation (expansion) in the cranial blood vessels, while headache pain is caused by vasoconstriction (narrowing) of the blood vessels.

Therefore, migraine medications are largely vasoconstrictors: first the ergots and then, in the 1990s, triptans, which are serotonin receptor agonists.

Most at the table have tried a host of medications—Imitrex injections and pills, Treximet, Relpax, Maxalt, Zomig, Amerge, Fioricet. Triptans with naproxen sodium. Dilaudid with Phenergan injections (for migraines severe enough for an ER visit.)

“I take topiramate (Topomax) daily, which is designed to prevent migraines, and in the three years since I’ve been taking it, the number of migraines I have and their severity has gone down considerably,” says one participant. “I also take rizatriptan, a triptan that I call ‘the magic pill.’ It stops the bad feedback loop that leads to a migraine.”

Participants agree that taking medicine too late is useless. “I’m trying to learn not to be stingy with my pills and to take one when I feel the first symptoms, whether a light headache, or nausea, or an aura,” says one. “I keep up with my refills so I never feel like I’m going to run out.”

Several of the participants say they treat their migraines with Botox. “It’s like I’m getting away with something,” says one. “The first time I didn’t have a headache after Botox, I couldn’t believe it. It’s 37 injections all over my head. I go every 90 days for injections, and I’m mostly free of migraines for the first time in my life. I didn’t know people were living like this, without pain.”

Esper makes a point to ask patients what is going on in their lives—relationships, work, diet, travel—since migraines can have environmental triggers. “An accountant comes to me every March to get ready for tax season,” Esper says. “Stress and sleepless nights can bring migraines on.”

One participant’s migraines had been misdiagnosed for 11 years as sinus headaches. Another went on vacation for 10 days and didn’t have one the entire time—she wasn’t sure if it was due to change of climate or less stress.

Estrogen, through hormone replacement therapy or oral contraceptives, can help or hurt, says Esper.

Some antidepressants are used to treat migraines—Esper recommends tricyclic antidepressants as first-line therapies. Other antidepressant drug classes may not work as well. “Cymbalta—it’s like putting my brain in a sling,” says one participant. “My knitting gets looser. I’m more relaxed.”

A “what if” question is posed: What if you had never had migraines? Some participants say they might have taken part in more activities, been more social, worried less.

Esper, who first experienced migraines in medical school and residency when he was under pressure and getting little sleep, says his migraines have one upside: “They have given me more empathy and compassion for my patients.”