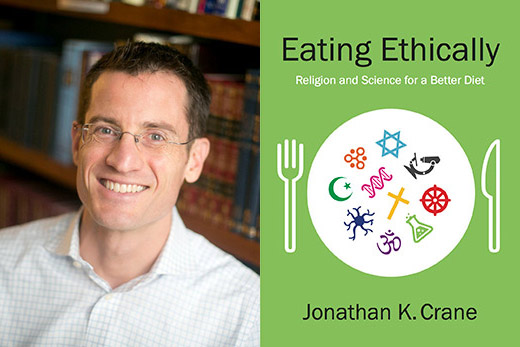

When Emory bioethicist Jonathan Crane began researching his latest book, “Eating Ethically: Religion and Science for a Better Diet,” he decided that one of the best ways to gain inspiration for such a vast, multifaceted topic was to introduce it in the classroom.

“I wanted to explore these issues alongside my students,” Crane says. He eventually created three courses on the theme, the first one lecture-based with Crane as sole professor, the second a team-taught course with colleagues from anthropology, law and public health.

For the third class, funded through Emory’s Center for Faculty Development and Excellence as auniversity course, undergraduate and graduate students from across Emory competed last spring for just 20 slots. Crane was joined by a dozen guest lecturers, also from across the university, who were experts in their fields.

“The courses reinforced for me how complex eating really is,” says Crane, who serves as Raymond F. Schinazi Scholar in Bioethics and Jewish Thought at Emory’s Center for Ethics. “It was invaluable for me to share with my students some of my emerging research, and they helped illuminate for me different interpretations of the material I was wrestling with.”

“Eating Ethically” began as an op-ed Crane wrote for The New York Times in 2013. His column, titled “The Talmud and Other Diet Books,” stemmed from his interest in eating-related issues, specifically obesity and other major health problems confronting huge segments of the population.

“I wanted to look at those complicated issues from a Judaic lens,” says Crane. “I found that Judaism has ancient wisdom about healthy and holy eating, in addition to kashrut, or strictures about cooking and holy foods.”

From that springboard, Crane integrated religion, philosophy and the science of eating/metabolism to explore an array of questions both in the book and in the classroom: Why has our eating become so troublesome? What does it mean to be full? How can we make contemporary eating more adaptive, healthy, ethical?

“What I found in my research is that all three fields — philosophy, physiology and theology — agree that it is far better for an individual person, and for society generally, if one eats less than what one bodily can,” Crane explains. “In other words, not eating until you’re full, but eating until you are sated.”

One of the most powerful stories illustrating this point comes from an Islamic textual tradition that describes a competition among sages from different civilizations, says Crane. Each sage was challenged to describe a medicine that results in no sickness.

According to the text, the final sage’s answer is deemed to be the best: to refrain from eating until you are actually hungry and to stop eating before you are full.

Unfortunately, says Crane, “the contemporary American food environment problematizes both those things.”

Take-out containers for foods, drinks and snacks on the go make it possible for us to eat constantly, he says, “so we’re never actually building up an appetite.”

Plus, many of the foods in the American diet are what Crane calls “hyper-palatable” (very tasty), stuffed with salts, sugars and fats, or manufactured synthetics meant to imitate the flavors/textures we crave.

Many of these foods’ nutritive value is negligible, he says, “and they trick us into eating well beyond what our bodies can actually benefit from.”

It’s not that eating is bad, says Crane; in fact, developments in cooking and eating have advanced civilization. “Human beings evolved around fire, around cooking,” he says. “It was around the fire that people could transform raw foodstuff into foods that could be more easily consumed.”

What’s more, “evolutionary biologists have shown that human brains exploded in size concurrently with increased use of fire,” he says. All that delicious, digestible cooked food made ancient peoples stronger and smarter.

“That’s where society flourishes — at the table,” says Crane. “This is why all religions require feasting at some point during the year, because they want people to gather, at times, around a bounty.”

But many religious faiths also require fasting on occasion.

“What I’m suggesting is that those feasting activities ought not be our daily activities,” says Crane. “During the rest of the year, we need to east less than what we bodily can,” which is the difficult part.

“Our contemporary food environment encourages us to eat according to external cues,” he explains. Cues include everything from food ads and restaurants’ serving sizes, to the accepted timing and content of meals and even the way foods are priced.

Of course, none of these external cues will be disappearing anytime soon, and Crane isn’t expecting anyone to unlearn external food cues, but he’s hoping we could learn or re-learn some internal ones.

For Crane, it all comes down to the eater.

“Corporations are not putting the foods in our mouths. Governments are not putting the foods in our mouths. We ourselves are the individuals who feed ourselves at each and every eating moment,” he says. “Reclaiming that agency is critical psychologically; we need to be the owners of our own eating strategies.”