The truth came crashing home last year—a perfect storm of faulty genetics, the unrelenting march of age, and every athletic mishap Kimber Williams had ever stumbled through.

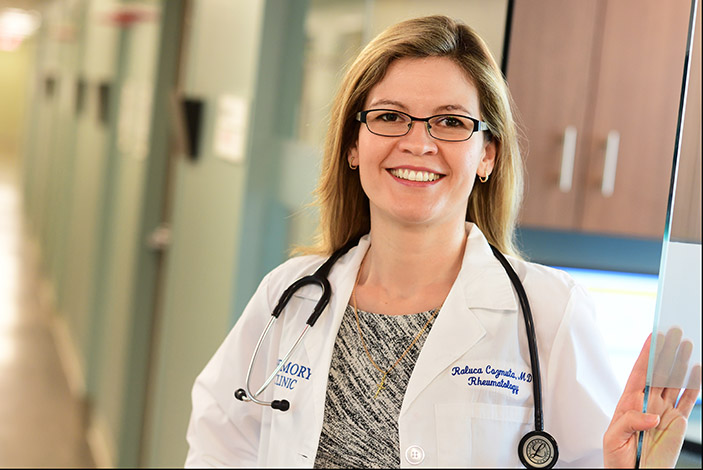

After watching two kinds of arthritis stiffen her mother's joints—leaving her with fingers pinched into what she called her "flippers" and staggering knee pain—Williams now says she shouldn't have been shocked to hear Emory rheumatologist Raluca Cozmuta gaze thoughtfully at her own X-rays and say the words she never wanted to hear.

Osteoarthritis.

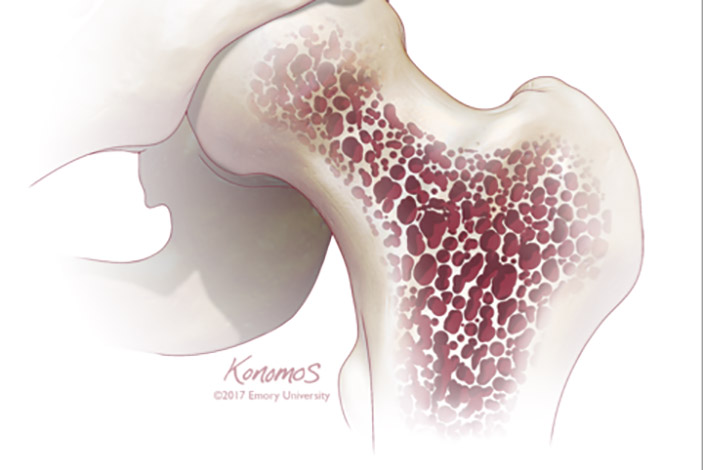

The most common form of degenerative joint disease, affecting millions worldwide, osteoarthritis (OA) is both quite ordinary and, for many people, somewhat inevitable. The cause is deceptively simple: Over the years, the slick rubbery cartilage that pads and protects the ends of our bones simply wears down, eventually leaving bone rubbing painfully against bone.

Like a brake pad worn thin, this erosion can occur in almost any joint in the body, although it most commonly shows up in knees, hips, hands, and spines. There is no miracle cure; treatments to quell discomfort typically range from anti-inflammatory pain relievers, physical therapy, and cortisone injections to surgery.

But lately, a non-surgical alternative has been gaining attention—a treatment that relies upon the power of the human body to help heal itself.

About five years ago, physicians at Emory Orthopaedics and Spine Center were among the area's first health care providers to begin offering regenerative stem cell therapy, a treatment for osteoarthritis and related joint issues that harnesses the ability of a patient's own stem cells to repair damaged tissue, reduce pain, and promote healing.

It works like this: Stem cells are extracted from a patient with a needle—usually from abdominal fat (adipose tissue) or bone marrow within the hip—and placed into a centrifuge, where the sample is spun rapidly to isolate the stem cells and create a rich concentrate. Within a matter of minutes, those cells are injected back into the patient's damaged joint to help kick-start healing.

All told, the in-office procedure takes about an hour and a half, with little downtime, discomfort, or side effects for most patients. Harvesting the adult stem cells directly from patients reduces the risk of rejection; many report feeling marked improvement in their joint within one to three months.

For Ken Mautner, who practices sports medicine at Emory Orthopaedics and Spine Center, stem cell therapy represents a natural next step in regenerative medicine.

Mautner is a leader in the field of orthobiologics, which uses cell-based therapies and biomaterials to enhance healing, empowering the body to help repair itself. About nine years ago, he began using platelet-rich plasma therapy to help patients with osteoarthritis and joint damage, expanding to stem cell therapy around 2012.

The power of the process lies within the cell. Stem cells are essentially the body's most fundamental raw material—specialized cells with the ability to make copies of themselves and the potential to differentiate into various types of cells for specific functions within the body. While there are several different types of stem cells, those thought to excel at promoting the healing of tendons, ligaments, and cartilage are mesenchymal stem cells, multipotent stromal cells commonly found in bone marrow and adipose (fat) cells, says Mautner, an associate professor of physical medicine, rehabilitation, and orthopaedics at Emory and director of primary care sports medicine.

The body typically keeps a ready supply of these powerful mesenchymal cells on hand to help repair injured tissues. And while there is little evidence that introducing a concentration of the cells can actually replace lost cartilage within a joint, they do have the ability to function as "very powerful signaling cells," encouraging the body to send in proteins such as cytokines—molecular messengers that slow down cartilage degeneration and regulate pain—and interleukins, a type of cytokine that can also dial down inflammation.

"Put them in a test tube, and you can get stem cells to grow into almost whatever you want," Mautner says. "Here, the goal is reducing pain and improving function, working to essentially turn off the death of your original cartilage cells."

Those cartilage cells could have been damaged from an old athletic injury, the wear-and-tear of everyday life, or by mechanical issues linked to the way you walk, exacerbated by obesity or simple genetics. The result is the same—pain, stiffness, and reduced range of motion.

Through stem cell therapies, Mautner sees an opportunity to fill a critical treatment gap for OA patients, providing an alternative between pain relievers and total joint replacement surgery.

Though some still consider the treatment experimental—the FDA is now considering how to regulate a number of stem cell therapies, which most insurance doesn't yet cover—Mautner and his colleagues are monitoring outcomes for 150-200 patients a year. And they're encouraged by what they've seen.