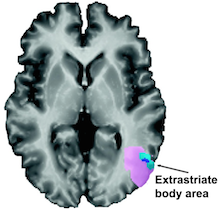

The EBA was shown in 2001 to respond selectively to images of the human body. The idea that comprehension of abstract concepts in the brain is built upon concrete experiences goes back many years.

Image from Lacey et al, Brain & Language (2016).

Listening to metaphors involving arms or legs loops in a region of the brain responsible for visual perception of those body parts, scientists have discovered.

The finding, recently published in Brain & Language, is another example of how neuroscience studies are providing evidence for "grounded cognition" – the idea that comprehension of abstract concepts in the brain is built upon concrete experiences, a proposal whose history extends back millennia to Aristotle.

When study participants heard sentences that included phrases such as "shoulder responsibility," "foot the bill" or "twist my arm", they tended to engage a region of the brain called the left extrastriate body area or EBA.

The same level of activation was not seen when participants heard literal sentences containing phrases with a similar meaning, such as "take responsibility" or "pay the bill." The study included 12 right-handed, English-speaking people, and blood flow in their brains was monitored by functional MRI (magnetic resonance imaging).

"The EBA is part of the extrastriate visual cortex, and it was known to be involved in identifying body parts," says senior author Krish Sathian, MD, PhD, professor of neurology, rehabilitation medicine, and psychology at Emory University. "We found that the metaphor selectivity of the EBA matches its visual selectivity."

The EBA was not activated when study participants heard literal, non-metaphorical sentences describing body parts.

"This suggests that deep semantic processing is needed to recruit the EBA, over and above routine use of the words for body parts," Sathian says.

Sathian’s research team had previously observed that metaphors involving the sense of touch, such as "a rough day", activate a region of the brain important for sensing texture. In addition, other researchers have shown that motion-related metaphors engage parts of the brain involved in motor control or in the perception of movement.

Relative to those previous findings, the researchers were surprised to find that body part metaphors did not tend to activate areas of the brain linked to motor control or the sense of touch.

"It is a negative result, but just because we didn’t detect signals with these brain imaging methods doesn’t mean subtler connections don’t exist," Sathian says.

The Brain & Language paper includes analysis of "resting state connectivity", showing that the EBA appears to communicate with language processing areas of the brain, even while someone is not listening to a metaphor. Follow-up research could test whether magnetic stimulation of the EBA interferes with processing of body part metaphors.

In one reported case of damage to the brain including the EBA, the affected person was impaired in using body part words to refer to inanimate objects (the teeth of a comb or the arm of a chair). Separately, the EBA was recently shown to be involved in understanding the meaning of gestures.

Research on metaphor comprehension can inform rehabilitation approaches for someone who has had a stroke or traumatic brain injury affecting the ability to process language.

"Engaging their senses multimodally may be a way to bootstrap rehab for those individuals," says Sathian, who is director of the Rehabilitation R&D Center at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

The first author of the paper is senior research associate Simon Lacey, PhD. Collaborators at Auburn University and Purdue University contributed to the paper. The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (BCS1125756) and the Veterans Administration.