His collapsible white-tipped cane leading the way, Jesse James Jones, Jr., wasn’t sure what to expect when he tentatively entered the Starbucks coffee shop across from Ponce City Market on Monday afternoon.

With soft lighting and light jazz music — punctuated by the hiss of an espresso machine — it felt like a far cry from a traditional law office, the Veterans Administration (VA) or any of the other resources Jones might visit to seek help filing a claim for military disability benefits.

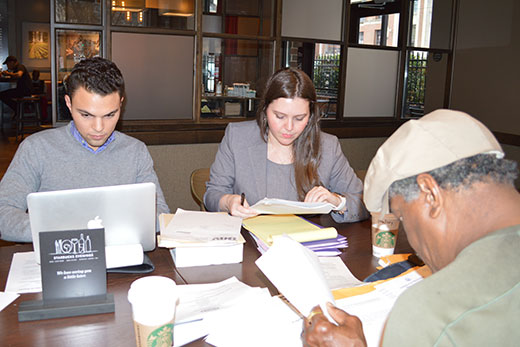

Seated at a long table with her laptop, Keely Youngblood 16L rose to meet him.

For Youngblood, a recent Emory Law School graduate who is one of the two full-time AmeriCorps legal fellows who helps supervise nearly two dozen law student volunteers with the Emory Law Volunteer Clinic for Veterans (VCV), this is a satellite office. And twice a month the coffee shop hosts “Military Mondays” — a laidback, walk-in clinic intended to lend U.S. service veterans answers, advice and encouragement.

But mostly, she gives hope.

Founded in 2013, the Emory VCV provides pro bono legal services for U.S. veterans and their families, assisting them with negotiating the often-overwhelming bureaucracy of seeking disability benefit claims before both the VA and subsequent appeals proceedings.

Through the support of the Military-Veterans Section of the Georgia Bar Association and the Military Legal Assistance Program, the student-run clinic was launched to provide free legal assistance to area veterans struggling to find their way in the system.

Many have moved back into civilian life with service-related injuries, including post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury, that can create barriers to self-advocacy. Others also grapple with legal issues related to their disability claims, discharge upgrades or other civil matters.

“We can help," says Drew Early, an Atlanta attorney and co-director of the VCV who teaches veterans law as an adjunct professor at the Emory School of Law.

“I work with smart, eager students and local attorneys who volunteer their time to respond to a tremendous need in the state that’s not being met by conventional procedures, which can be ponderous and overwhelming,” says Early, who is himself a West Point graduate and retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel.

Clinic impacts veterans, students

To date, the student-run clinic has assisted with 158 cases, aiding in the recovery of some $4.7 million in expected lifetime benefits for its clients, who range from World War II veterans and their spouses to those only recently discharged from active duty.

“Georgia has 776,000 veterans by the VA’s count,” says Early. “When you add to that active-duty military in the nine different bases in Georgia, and family members, there are potentially about 2 million people out there who could be eligible for VA benefits — yet there is only one VA office in the state to handle all of that.”

Not only is the clinic impacting the lives of veterans and their families, it’s also providing valuable first-hand experience to Emory law students, along with a chance to network with and learn alongside lawyers from some of Atlanta’s top firms.

“Overall, it’s reflective of Emory,” says Early. “This is the Law School’s 100th year and our motto is ‘100 Years of Public Service.’

“Through the clinic, students see how they can make a difference and why it’s important,” he adds. “And it also helps them understand how to deal with bureaucracies and administrative agencies in order to get things done.”

For volunteers like Youngblood, an Equal Justice Works AmeriCorps Legal Fellow, the chance to make a difference in the lives of veterans has had a profound personal impact.

“Veterans law is a quickly-evolving field with a lot of room for nuanced arguments and legal creativity,” Youngblood says. “In my position as a fellow, I get to see students grow more empowered by the day as they learn to take ownership of their legal analysis, and I get to see veterans grow more empowered when they come to the clinic and find energetic people ready to listen.

"The clinic gives me the resources to do good work for my own clients while also developing relationships with students and attorneys in the community," she says. "It makes it easy to roll up my sleeves and get to work every day."

The experience has also offered an illuminating post-graduate education into “the litany of diseases that veterans can face as a result of Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam to how prevalent PTSD among that community really is,” she adds.

Though discouraged by the barriers that veterans and their families routinely face, Youngblood finds the work motivating.

“Seeing clients get back on their feet after a hard knock with humor and optimism, as many of them can do with just a little help, makes me a better lawyer and a better person,” she says.

Building bridges

As president of the Georgia regional chapter of Blinded Veterans Association, Jones first heard of the Emory VCV at a state conference in April that was attended by Mallory Ball 15L, the clinic’s other AmeriCorps legal fellow.

Jones decided to drop into the Military Monday walk-in clinic this week in part for his own disability claims questions, but also to test the system for fellow veterans, who lost their vision or have had it adversely impacted as a result of service injuries and exposures.

“I was curious to go there first, before recommending it to others, in order to assess first-hand how things work,” he said. “The experience was great, definitely more than I hoped for.”

Nursing a free cup of coffee from Starbucks, Jones worked with the young attorney for nearly an hour, then stayed on to help her consult another visually impaired veteran.

Youngblood patiently asked questions and gathered facts, “strategically going over critical points that might have been missed at a service office for veterans,” observed Jones, who served in the U.S. Army and Army Reserves in the late 1970s until receiving an honorable discharge in 1983.

“From the records I had, it appears that I have some hope that I could be awarded for my claims,” Jones said. “Not knowing the law, Keely was giving me some hope.”

For Youngblood, there is value in that.

“When veterans are reintegrating to society I think they have a really long bridge to build,” she says. “Sometimes it feels no one is available to help them.

"The clinic cannot build the whole bridge, but I do think the clinic uses its resources well to help veterans lay a lot of the bricks," she says. “If we can do that well, lead them where they need to be to take ownership of their lives, I think that is important and rewarding.”