Researchers at Emory University, the University of Georgia, and the Georgia Institute of Technology, along with national and international collaborators, will investigate the mechanisms behind “resilience” following malaria infection.

The investigators believe learning why malaria causes acute, potentially lethal disease in some humans and animals, while others are much more resilient or tolerant, could lead them to better intervention strategies for malaria and other diseases, including new and better drugs.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Army Research Laboratory (ARL) are supporting the research through a $6.4 million contract. The research partnership is part of DARPA’s THoR (Technologies for Host Resilience) program and is termed the HAMMER (Host Acute Models of Malaria to study Experimental Resilience) project.

HAMMER is one of a few projects in the THoR program, established for a three-year period, covering a variety of diverse host-pathogen model systems. The HAMMER project uniquely focuses on malaria and its effects on human and non-human primate hosts.

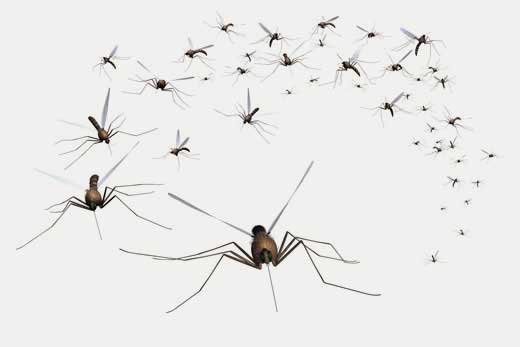

Malaria, which is transmitted through mosquito bites, is the most widespread human parasitic disease and is endemic in approximately 100 countries. It causes fever, pain and other acute responses, and in severe cases it can become deadly within days of the onset of symptoms.

“Malaria is a potentially lethal disease, but resilience in some people and non-human primates allows them to control the disease and avoid adverse outcomes, so that the infection is not incapacitating,” says Mary R. Galinski, PhD, principal investigator for the project and professor of medicine and infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine, Emory Vaccine Center and Yerkes National Primate Research Center.

“Our goals are to identify host features associated with resilience, thinking beyond the host’s immune response into the realms of physiology, biochemistry and pathogenesis, and develop interventions that could enhance that resilience.”

In addition to Galinski, key leaders of the THoR HAMMER project include Juan B. Gutierrez, PhD, associate professor of mathematics and bioinformatics at the University of Georgia, and Rabindra Tirouvanziam, PhD, assistant professor of pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine.

The project includes more than 40 established investigators in infectious diseases, systems biology, physiology, pathology, immunology, genomics, bioinformatics, pediatrics, cardiology, pulmonology, biomedical engineering, and mathematics at the three institutions, and through other collaborations.

THoR’s HAMMER project focuses on the malaria parasite Plasmodium knowlesi, which can infect both humans and non-human primates. Plasmodium knowlesi causes mild chronic infections in some monkeys, such as long-tailed and pig-tailed macaques, which are its natural hosts. However, it causes severe, virulent infections in other monkeys, such as rhesus macaques.

Using systems biology approaches, the THoR’s HAMMER team will generate large datasets on characteristics of P. knowlesi infection in the two types of non-human primates and in humans. They will then develop and apply mathematical models to compare and contrast the different scenarios of infection to identify particular host features associated with resilience. This may yield insights that could lead to novel interventions for malaria, including new drugs.

The researchers will use surgically implanted telemetry devices to gather continuous real-time physiological data from the two types of monkeys, before and during infection, including temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and mobility. The HAMMER project will investigate correlates of physiological signals captured via telemetry with clinical and molecular variables, to detect signatures of the onset of severe disease.

The team also is collaborating with Balbir Singh, professor and director of the Malaria Research Centre at the University of Malaysia, Sarawak, to examine a large cohort of samples from human P. knowlesi infections. Malaysian Borneo is the epicenter of a significant animal-to-human public health threat in Southeast Asian countries and P. knowlesi accounts for the majority of Borneo’s malaria cases. Such zoonotic infections have been reported in other parts of Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar and Vietnam.

“By combining the new technology of telemetry devices in non-human primates with data from human infections, our project will both deepen understanding of malaria caused by P. knowlesi, and generate valuable information to address other types of malaria, including disease caused by P. falciparum and P. vivax, the most common malaria parasites worldwide,” says Gutierrez.

The researchers' ultimate goal is to test candidate therapeutic interventions in highly susceptible hosts with the aim of reducing disease severity and death in the absence of effective antimalarial chemotherapy, or in conjunction with antimalarial chemotherapy. If successful, such host-directed therapeutic strategies could be available for use by people in need, whether they are infected with P. knowlesi, other species of Plasmodium, and possibly other pathogens. These challenging goals are fitting with DARPA’s track record taking on some of the world’s most difficult and creative research projects, venturing into unchartered scientific territory.

The THoR’s HAMMER project builds upon the scientific infrastructure of the Malaria Host-Pathogen Interaction Center (MaHPIC), a malaria systems biology partnership between Emory, UGA, Georgia Tech, and the CDC Foundation, established in 2012 with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN272201200031C. Through its robust, multi-institutional research partnership and global collaborations, MaHPIC has used technological advances to conduct innovative systems biology research in non-human primates and applied mathematical modeling tools to integrate large, diverse datasets, including from human samples. The MaHPIC and HAMMER team members will work collaboratively to further the distinct goals of both projects.

“Our systems biology team, which has become well-established through our MaHPIC consortium, plans to positively impact the work of all THoR projects by continuing to promote cross-fertilization of ideas both within our team and among all THoR project participants nationally,” says Tirouvanziam.