As curator of modern political and historical collections at Emory’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, Randy Gue is always on the lookout for material that helps complete the cultural puzzle that is the American South.

Last year, he realized that he held a piece of it himself.

Growing up in Atlanta in the early 1980s, Gue was drawn to the community’s burgeoning punk rock scene, which was fed by both local bands and nationally known acts that passed through the city.

Although hardcore punk stood in stark contrast to broader Southern culture at the time, Gue and other fans found within it a life-changing wave of creativity and community. In many ways, it became his second family.

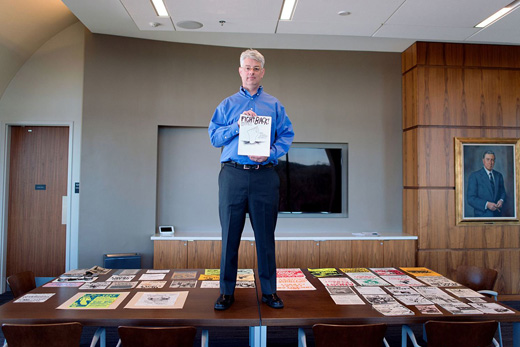

For years, Gue collected mementos from that time — concert fliers and fanzines, bumper stickers and posters.

Last year, he and his friends Randy DuTeau — former lead vocalist for the ‘80s Atlanta hardcore band Neon Christ — and Nick Rosendorf donated their punk-rock memorabilia to Emory’s Rose Library, creating the seedbed for a new collection.

Since then, the collection documenting the hardcore punk rock and alternative music scene in Atlanta from 1980 to today has grown, as others have stepped forward with donations.

When the collection became the focus of recent online articles produced jointly by The Bitter Southerner and ArtsATL, Gue reports that his phone “exploded” with messages from fans offering their own donations, graduate students doing research on social/cultural/political aspects of the punk rock movement, and even a researcher from the United Kingdom eager to study it.

Emory Report caught up with Gue to talk about Atlanta’s punk rock scene and the start of a new collection that is stirring public interest.

How did you discover punk rock?

Music was always important to me. One thing led to another and I ended up buying a seven-inch record by Black Flag, one of the seminal hardcore punk bands. One side had the song “Six Pack”; on the flip side were the songs “I’ve Heard It Before” and “American Waste.” I’d never heard anything like it.

Then in August 1983, I went to the Metroplex (in Atlanta) and saw my first punk show, the California-based band Youth Brigade and Atlanta’s own DDT. In two hours, my life went from boring black-and-white to Technicolor. It was one of those Saul-on-the-road-to-Damascus moments. I saw the light.

The music was great, but what really spoke to me was the scene’s Do-It-Yourself philosophy of creating their own culture. I stumbled onto a group of people not much older than me who started their own bands, booked their own shows, put out their own records, and made their own fanzines. It was eye-opening.

How did the punk rock scene fit into Atlanta at the time?

Atlanta was a different town back then — a smaller place culturally and geographically and more a part of the Bible Belt. So hardcore was on the margins of the margins. At the time, R.E.M. was considered so radical that the local rock radio station — 96 ROCK — wouldn’t play them, so there was no chance of hearing Black Flag, the Dead Kennedys, DDT or Neon Christ on the radio.

Did the movement mirror what was going on in other places?

Yes, Atlanta was part of a nationwide DIY network, connected by snail mail, fanzines and long distance phone calls.

Why create a collection dedicated to the punk scene?

The Rose Library is charged with acquiring, preserving, arranging, describing and providing public access to materials of lasting historical value. I’m responsible for our collections that document the history, culture and politics of Atlanta, Georgia and the South.

One of my goals with this collection is to document how the city participated in the national avant-garde culture, to demonstrate that what was going on in places like New York, Los Angeles and Chicago also happened here in the South. I am also trying to document the genesis of DIY culture in the city. The Atlanta Punk Rock collection represents one piece of a much larger puzzle.

The amazing thing about punk rock and hardcore is that it is still going strong. It’s changed, of course, but the music and DIY ethos are still relevant — they still mean something to people in the scene today.

How did the collection get its start?

The collection began when my friends — Randy DuTeau and Nick Rosendorf — and I donated our own collections from the 1980s. The great thing now is that the community is building the collection. Successive generations of participants are now adding materials from their time on the scene, and that’s what the collection should be.

What does it contain?

Fliers and posters from shows, Atlanta fanzines, set lists, stickers and patches. Some of the folks brought in seven-inch singles, LPs and CDs by Atlanta bands. And there are even cassette tapes, which are making a comeback.

All these things are ephemeral: they were produced for a very specific time and place. It is extraordinary that so many people have held onto so much. And people keep donating stuff. The collection literally changes from week to week. It is a living collection.

Is this the first public collection of its kind in Atlanta?

As far as I know, it’s one of the first in the country. There is a lot of academic interest in DIY culture right now because it has become one of the defining aspects of the Internet age and the digital economy. The interest is only going to grow over time.

What has resurrecting these materials meant to you?

The people I met and the experiences I had in the scene made me who I am. It shaped me. It has been a lot of fun to give back to the scene, if you will, by working to document it.

But the best part is being able to share these unique materials with a larger audience. Like any collection at the Rose Library, the meaningful part is making it available to everyone.

Editor’s Note: To learn more about the punk rock collection, or to donate materials, email Randy Gue.