From his office inside Emory's Central Steam Plant, Jody DiCarlo can detect the low, steady rumble of the plant's massive boilers — one of which sits only a few feet outside his office door.

To a visitor, the sound is indistinguishable from the raucous symphony of mechanical noise that permeates the plant. But to DiCarlo, plant operations manager for Emory's steam plant, it's distinctive from all other noises that rattle, whistle and roar throughout the facility, and a sound he takes comfort in.

Like a heartbeat, it offers assurance that Emory's boilers are working. Without that rumble, something would definitely be wrong.

In many ways, the steam plant is the heart of the University's heating system, working like a giant kettle to warm and humidify offices, classrooms and residence halls; sterilize equipment in Emory's hospital and clinics; keep temperature-controlled research in check; and assist with food preparation and sanitation in campus kitchens.

On a mild day, the boilers create around 100,000 pounds of steam an hour; on a cold day, that can double to 200,000 pounds per hour. In a year's time, the plant churns out about 800 million pounds of steam, according to DiCarlo.

Emory's five central boilers are numbered 5 through 9 — 1 through 4 were long-ago retired — and DiCarlo and his team know the strengths, personalities and unique quirks of each boiler as well as they do those of their own children.

This spring, the plant crew will begin the behemoth task of decommissioning and replacing boiler 5, which will be disassembled in April to make way for a new boiler — number 10 — set to arrive this summer, says DiCarlo.

A workplace under pressure

Streaming away from the plant — unseen to the campus community — are the plant's arteries, a network of roughly six miles of underground pipes that shoot 360-degree steam to 55 buildings across the Atlanta campus.

The system also includes a series of about 40 smaller outlying boilers scattered around campus, which primarily serve as water heaters.

Tucked into a canyon between the railroad tracks and Eagle Row, the plant is largely hidden from public view, marked primarily by a telltale row of five towering stacks — each connected to a boiler — that release steam, gases and water vapor, sometimes visible as a white plume on a crisp winter morning.

Anything released from those stacks must meet strict EPA standards, says DiCarlo, who uses them as visual barometers of how the boilers are performing.

"The worst thing that you could see coming from those stacks is black smoke — you wouldn't want that," he says. "Every morning that I come to work I make a mental note to check the stacks."

Each of the plant's boilers has the capacity to create 100,000 pounds of steam per hour, running primarily on natural gas or, more rarely, fuel oil if the gas supply is interrupted, which has happened. "Hurricane Katrina caught everyone by surprise," DiCarlo says. "Our natural gas supply was shut off and for two to three days, we had to rely on reserve oil."

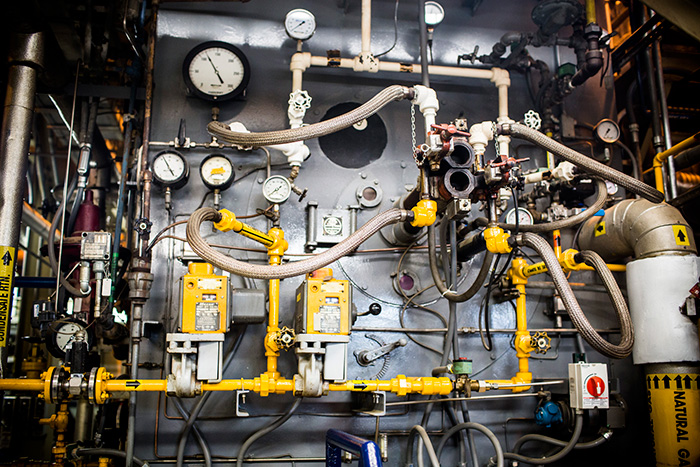

Taken together, the boilers, polishing room (where water feeding the boilers is purified) and water and fuel tanks comprise a workplace under pressure: high-pressure steam, high-pressure gas, and fuel that is atomized.

That's why constant monitoring is critical, says DiCarlo. Display screens stationed strategically throughout the plant, as well as a central control room, track gas and water levels, steam pressure and temperatures, reserve tank levels — you name it, they're probably watching it.

"It's a 24/7 operation," says DiCarlo, who coordinates shifts that must be staggered around the clock. "If we go down, it affects every building out there."

Balancing combustible components

Working around combustible components of fire, flammable gas and oil, and steam could be dangerous, but for DiCarlo and his team, the key to this job is all about balance.

The water that feeds the boilers is "as close to pure as is possible," says DiCarlo, to help prevent residues from gumming up the system. Working together, water and heat feed the plant's "steam cycle."

The new Emory WaterHub, an on-site water reclamation and recycling system that utilizes eco-engineering processes to clean campus wastewater for non-potable uses, now provides reconditioned water to the steam plant, replacing water previously lost to evaporation and "helping keep our water tank full," says DiCarlo.

In some ways, the WaterHub, which officially opened in April, has become a laboratory. The chemistry of the reclaimed WaterHub water is tested every two hours to ensure purity. Using reclaimed water, as opposed to buying water from DeKalb County, will create cost savings for the University.

In addition to DiCarlo, the six-man steam plant crew includes senior plant operator Frankie Parker; plant operators Chip Lein, Brian Wiley and Brian Koch; and plant operations specialist Steve Crumley.

Most, like DiCarlo, are U.S. Navy veterans who learned the trade working on boilers used to power Navy destroyers, aircraft carriers and battleships — all told, a unique environment, he notes.

Tending the boilers is a 24/7 job and DiCarlo is a stickler for proper certification and training. There is simply too much at stake. With good care and upkeep — and a steady diet of pure water — these multi-million dollar boilers can last for 60 years, he says.