Steven Mets is used to blending in—and being misunderstood.

After all, he seems like a typical 21-year-old college student, into gaming and the outdoors. "I've had doctors look at me like, 'Why are you here? You're fine,' " says Mets, a student at Clemson University.

But in his case, appearances are deceiving.

Look more closely and there are clues that Mets is, in many ways, exceptional. Take the scars on his body, remnants of a series of heart surgeries that started when he was just four days old (and that he expects will someday include a heart transplant.) Or his panoply of pills, the type of medications usually prescribed to much older adults. You might see his roommates lifting heavy objects for him, or, until recently, slowing down when walking up hills to make sure he could keep up.

Mets was born with a rare congenital heart disease called Shone's complex, involving multiple cardiac defects. He has a pacemaker, a bovine valve, and a mechanical valve that all help keep his heart going.

He is one of a growing number of adults now living with congenital heart defects (CHDs) that, a few decades ago, would have been a sure death sentence. "Someone who was born in the 1950s with a heart defect—just about any heart defect that wouldn't spontaneously resolve — their chances to survive to adulthood were poor," says Wendy Book, Mets's cardiologist and director of Emory's Adult Congenital Heart Center.

Patients with a hole in their heart or a missing chamber would rarely age out of a pediatric practice and grow up to need adult health services. But in the past few decades, a series of medical advances began extending these children's lives, sometimes just for a few years — and then a few more.

Treatment is advancing so rapidly that even a five-year fix will often buy the patient enough time that a new treatment is available when the last one stops working. "That can make a huge difference in giving them a chance at the life they want so badly," Book says.

When the first wave of children with CHD grew too old for pediatric cardiology services, they sometimes found themselves out of competent medical hands. "Nobody was prepared to take care of them when they grew up," says Book, a professor of medicine at Emory.

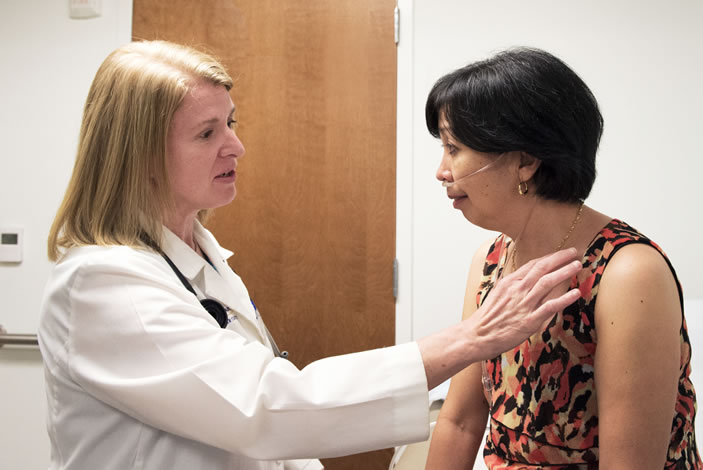

Cardiologists specializing in adults are trained to help patients with blocked arteries and cardiovascular disease. As Mets discovered, most had rarely if ever seen a patient with unusual circulation, valve problems, or only one pumping chamber of the heart, and the complications caused by these structural issues. If adult patients with heart defects required surgery, they often ended up back at a pediatric hospital with a pediatric cardiac surgeon.

The amount of care these patients require is both time-consuming and expensive. "But when you're talking about people with 50 years ahead of them, how can you not put forward the resources to help?" asks Book.