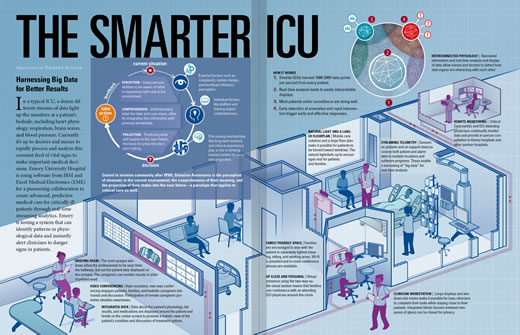

In a typical ICU, a dozen different streams of data light up the monitors at the patient's bedside. Currently it’s up to doctors and nurses to rapidly process and analyze this constant feed of vital signs — heart physiology, respiration, brain waves, blood pressure — to make important medical decisions. Emory University Hospital is using software for a pioneering collaboration to create advanced, predictive medical care for critically care patients through real-time streaming analytics. Emory is testing a system that can identify patterns in physiological data and instantly alert clinicians to danger signs in patients.

Q&A: Dr. Tim Buchman

Timothy Buchman

Professor of Surgery and Anesthesiology Tim Buchman, founding director of Emory's Critical Care Center, is in charge of integrating ICUs throughout Emory Healthcare. He also has been an airplane pilot for more than four decades.

What are the primary ways intensive care units (ICUs) are going to change during the next decade?

ICUs will focus on providing the "right care, right now, every time" by engineering consistency and reliability into every process. Standard communications, evaluations, treatments, and assessments form the foundation of high-reliability care. This is the same approach that has been used in other high-stakes human endeavors, such as commercial aviation and nuclear power plant operation.

What does Big Data have to do with critical care?

Making the best decision for each patient involves early detection that something is amiss and choosing the intervention with the best benefit/risk profile for that particular patient. Both depend on Big Data. Clinicians need computers to assist here for two reasons. First, no person can possibly interpret the several thousand data points each patient generates every second. Computers do this well. Second, we have selective memory. We are very good at remembering our most recent patient, less good at remembering what happened when we treated a similar patient four years ago. Big Data balances those memories and provides a much more accurate picture of how a current patient compares with all the other patients with seemingly similar conditions, allowing more personalized care.

You talk a lot about situation awareness (SA), a concept that originated in the aviation community after WWI. How does this apply to medicine?

Situation awareness is about forming the best possible basis for a decision through perception, comprehension, and projection. My favorite illustration is the way my dad used to drive and the way I drive. He had the same information, but he had it on a paper map, an odometer, and so on. We got lost—a lot. Today, I have a GPS navigator in the car and on my smartphone. I get a bird's-eye view of the car overlaid onto a map, along with traffic, weather, and turn-by-turn directions that represent the computer's best suggestion of what to do next. None of this threatens my authority as a driver—in fact, it frees me up to ask, "Do I really want to take this route to my destination?" We need to do the same thing for patient care: Perceive all of the data—history, physical exam, lab data, images, current treatments, and the patient's physiology. Accurately comprehend the data to form a "picture" of the patient's overall condition. And finally, use the data to predict the future in various scenarios—if no changes are made, if a test is ordered, if a treatment is started or stopped.

We have seen hospitals in the past several years strive to create a more relaxing, aesthetically pleasing, healing environment in their ICUs. Is there still more to be done?

Definitely. We need to make sensors less invasive and obtrusive. We need to move the alarms away from the bedside and get them to the caregivers who will act on them. We need to know when our treatments are not helping and, worse, when they are causing harm. And we need to optimize how critical care improves lives not just in the hospital but also once a patient and family go home.

You had a personal experience with being in critical condition. What did you learn?

When I was a physician in training, I was in an automobile collision—another driver "T-boned" my car. I ended up being a patient in my ICU. There were three key lessons I took from that experience: First, life is fragile. One must live strong and live well. You never know when it's going to be your turn to be the patient. Second, human touch and kind words are the greatest comfort. And third, there is no safety device better than a well-trained ICU nurse, just as a well-trained pilot is the best safety device in an airplane.

Recently, Emory doctors had the experience of caring for Ebola patients in Emory University Hospital's Serious Communicable Disease Unit, which is at its core an isolated, self-contained ICU room. What did critical care learn from this experience?

We learned that it really does take a team to get the best care possible to the patient while maintaining the highest achievable safety for the caregivers. Care of the Ebola patients included several complex therapies that could not have been done safely or successfully without tight team integration.

What most excites you about recent advances made in ICUs?

Advances in monitoring are helping us act more quickly and advances in treatment are helping us act more precisely. Together, those make for shorter ICU stays, better outcomes and happier patients.