While young scientists often find applying to the National Institutes of Health for their first research grants to be a significant challenge, Emory's strength in preparing students for this part of scientific life is becoming nationally recognized.

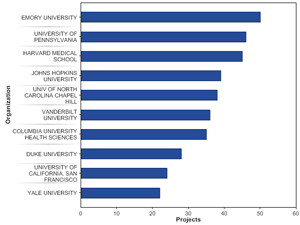

A total of 50 Emory students currently hold a Kirchstein-NRSA predoctoral fellowship from the National Institutes of Health, ranking Emory first in the United States.

For Emory, the numbers highlight years of nurturing a "deep bench," to use a sports term. A culture of training at Emory seeks to educate students in the skills required in today's competitive scientific environment: writing, presenting and communicating effectively as well as conducting core research.

Emory is currently first in the nation for the number of students with Kirchstein-NRSA pre-doctoral fellowships from the National Institutes of Health.

Biochemist Anita Corbett directs writing courses for several graduate programs in the Laney Graduate School's Graduate Division of Biological and Biomedical Sciences (GDBBS).

"We have excellent trainees and faculty sponsors, we have lots of support from GDBBS and Laney Graduate School, and we require formal training in scientific writing for second-year graduate students," Corbett says.

The "grants course" has various names, depending on which of Emory's graduate programs is being discussed, but its purpose is two-fold: to prepare students for their qualifying exams and to introduce them to the precise, rigorous thinking and writing needed to produce a competitive grant application.

"Most students say it's one of the best things they've had to do here, and the hardest," says Keith Wilkinson, director of GDBBS.

Preparing students for academia, other careers

In terms of numbers of active predoctoral NRSA fellowships in March 2015, Emory's neuroscience program and biochemistry, cell and developmental biology (BCDB) program ranked first and second, with 13 and nine grants, respectively. However, all GDBBS programs are represented, including MD/PhDs as well as nursing, public health and psychology doctoral students.

To be sure, graduate students at Emory are not just preparing for careers in academia. For example, the NIH-supported BEST program (Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training), a collaboration between the Laney Graduate School, Emory's Office of Postdoctoral Education and Georgia Tech, offers students exposure to careers in business, patent law, science communication and science policy.

"We are committed to expanding professional pathways for our students," says Lisa Tedesco, dean of Laney Graduate School. "We do this by implementing programming and training that is designed to make our students as prepared and competitive as they can be for a full range of collaboration within the biomedical and STEM workforce.

"Grant writing is an important part of this work, and I am proud not only of our students' successes in this area, but also of the grant training culture that our faculty and program leadership are working to strengthen," she notes.

Nationwide, the rising number of NRSA recipients in the last few years reflects a shift in policy by the NIH, which is encouraging graduate students to be supported through individual fellowships rather than through their faculty advisors' research project grants, Wilkinson says. Until recently, some Institutes within the NIH, such as the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, did not offer this type of individual predoctoral training grant, also called an F31.

At Emory, biochemist Rick Kahn, together with Ken Bernstein (now at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles), first developed a required course called "Hypothesis Design and Scientific Writing" for the BCDB program in the late 1990s. Kahn went on to implement a similar course for the neuroscience program. Now all GDBBS programs have something similar offered as a class for second-year students.

"We really consider it a writing course," says Lisa Parr, who has been teaching the neuroscience graduate program's equivalent class for several years. "The students learn to put together a research proposal in the NIH format, and how to support it by designing the best experiments. I try to emphasize to the students how to think about the grant application from the reviewer's standpoint."

Learning to ask for support

Neuroscience student Karl Schmidt, now in his fifth year, says Parr's instruction helped him develop a proposal for his project with advisor David Weinshenker, probing the roles of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine in the brain using optogenetic techniques.

"I had a decent idea of what I wanted to do," Schmidt says. "But I was less sure how to justify those ideas for a research grant, and that's where the class came in."

Schmidt and fellow neuroscience student Kelly Lohr say meetings with faculty mentors and upper-year students, and eventually a mock study section, both part of the course, helped them hone their writing. Even after the class, they and their advisors continued to edit what became their applications. To extend the training, Parr also teaches a summer workshop on the NRSA application process.

Nearly half the applications of Emory students are successful, and there are a number of tangible benefits for students. If their applications are approved, students receive a modest increase in their stipend ($2,000/year). The grant application process also helps to cement students' feelings of ownership for their projects, Wilkinson says.

Occasionally, students push back against having to learn to write a grant application when their postdoctoral plans focus on industry.

"I remind them, 'The game is the same, no matter where you end up working,'" Wilkinson says. "Someone else has the money and you have to convince them to give it to you. It's valuable to learn how to ask for support and justify what you want to do."