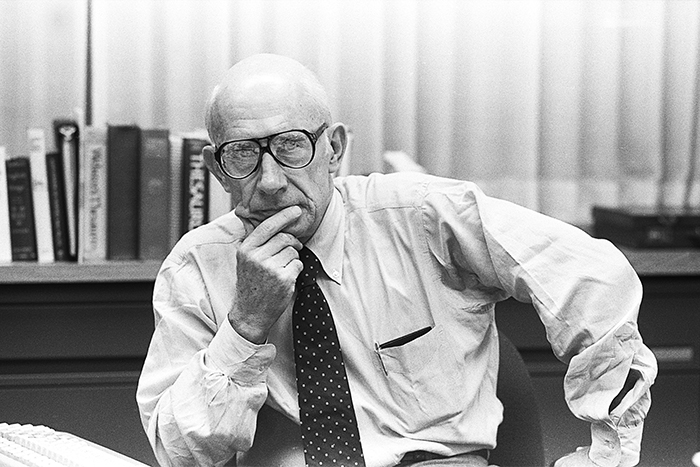

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Claude Sitton, an Emory graduate who earned national acclaim for his groundbreaking coverage of the some of the most turbulent years of the American civil rights movement, died Tuesday, March 10. He was 89.

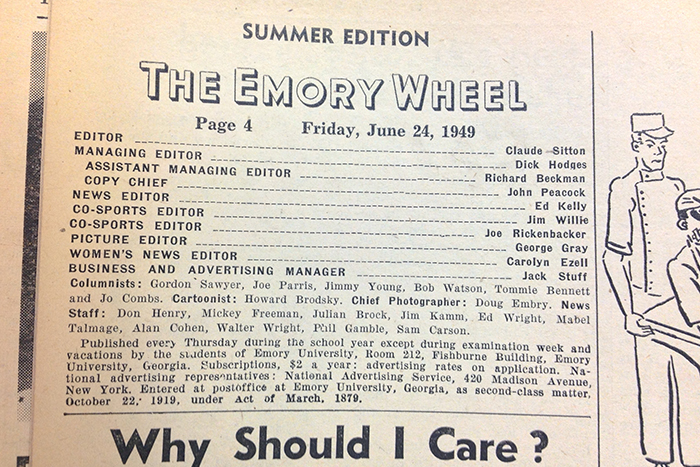

Sitton, 47OX 49C, was born at Emory University Hospital and raised in Rockdale County by a family deeply rooted in the American South. After attending Oxford College, he graduated from Emory in 1949 with a bachelor of arts degree in journalism. He went on to work for the International News Service and United Press in Atlanta.

He was later hired by the New York Times, where he served as a copy editor. After less than a year, Sitton was sent back to Atlanta as the newspaper's chief Southern correspondent, with a beat that would stretch across the Southeast.

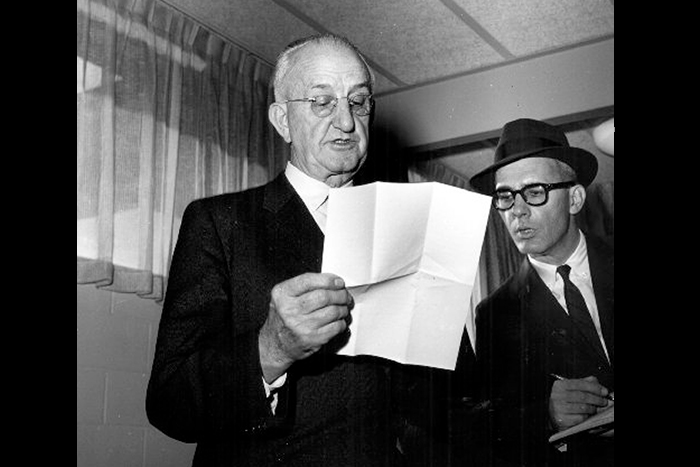

It was in that role that Sitton began to report on the civil rights movement. From May 1958 through October 1964, his stories documented such landmark events as the desegregation of public schools and universities, the sit-in movement, voter registration drives, beatings and bombings, the assassination of civil rights leader Medgar Evers, and the tumult of the Freedom Summer of 1964, as college students from across the nation flooded Mississippi to help register black voters.

Through his coverage of the unfolding movement Sitton would carve out his own legacy, seen today as part of the bedrock of modern American journalism, says Hank Klibanoff, James M. Cox Jr. Professor of Journalism at Emory, who wrote about Sitton's work in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, "The Race Beat: The Press, The Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation," which was co-authored by Gene Roberts.

According to Klibanoff, no one in the field of journalism at that time had as much impact as Sitton in covering the burgeoning movement. In his book, Klibanoff notes that "Sitton's byline would be atop the stories that landed on the desks of three presidents."

"Claude did some important things that no other journalist did — he got to places where no other journalist had been, and he got there first," Klibanoff says. "In fact, you could build an entire course around Claude, his work and his generation of reporters."

Through his coverage, Sitton came to represent "the gold standard" in civil rights coverage, Klibanoff said. "Wherever he went, that's where news editors at all the major media outlets would send their reporters."

"I've talked to network people in New York who said they would wake up every morning and pick up the New York Times and look for Claude Sitton's name and the dateline and see that he was at some off-the-beaten-path place in Mississippi or Alabama or Georgia and say to their correspondents, 'Why aren't you there?'"

Witness to history

Trusted by sources — civil rights leaders were known to carry his phone number — and known for his direct, unflinching newswriting, Sitton's dogged coverage often made him a witness to history, even as it was unfolding before him, Klibanoff says.

From school desegregation in Little Rock, Arkansas, and all-night riots in Mississippi when black Air Force veteran James Meredith was admitted to the University of Mississippi to police brutality against black demonstrators after the murder of Medgar Evers, Sitton's critical accounts would help open the eyes of a nation to the costly battle for civil rights.

"Claude just loved a good story," Klibanoff explains. "He saw it as his moral obligation as a reporter to see things with his own eyes. The only way to do that was to be there. If anything characterized the greatness of Claude Sitton, it was his constant presence on the scene."

During the height of the civil rights struggle, Sitton's coverage would take him from one political hotspot to the next, often requiring weeks on the road. In fact, his wife, Eva, would sometimes "just put a bed for him on the porch of the house, since Claude might come home in the middle of the night and head out before the sun was up the next morning," Klibanoff recalls.

Self-effacing and humble, Sitton "refused to see himself as important," Klibanoff says, "but he absolutely knew he was onto an important story – the New York Times was putting him on the front page day after day."

Over six and a half years, Sitton would file nearly 900 stories from across the region, according to The New York Times.

Inspiring future journalists

At Emory, Sitton left his own journalistic legacy, including the following contributions:

- Served as Emory Wheel editor-in-chief

- Helped re-establish a journalism program at Emory University in the mid-1990s

- Returned to Emory to teach from 1991 to 1994

- Served on the Board of Counselors at Emory's Oxford College from 1993 to 2001

- Honored as one of Emory's 175 history-makers in Emory magazine's 175th anniversary issue.

Sitton's papers, including correspondence, articles, speeches and more dating from 1958 to 2004, are archived in Emory's Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library. Emory also holds portions of his personal library, with many volumes annotated by Sitton.

Emory alumni — who count themselves lucky to have taken his classes — recall a tough journalistic standard-bearer with a deep empathetic core. Even today, they remember the classroom experience with a measure of awe.

Morieka Johnson Upton, 94C, was the only African American student in a group of about a dozen students who took Sitton's class on "Press Coverage of the Civil Rights Movement" in the early 1990s.

"He would talk and we would listen," she says. "I remember the gravity of his articles, which felt like a different time and place. Learning about the impact that a news article could have helped me grasp the fact that I wanted to be a journalist."

Not only did Sitton help her secure a coveted internship with the Southeast regional bureau of The New York Times, he also wrote a letter of recommendation for her to pursue graduate studies in journalism.

"He made me believe that I could do it, he listened to me, acknowledged me and heard me," recalls Johnson Upton, now a senior manager of communications for the Cox Media Group.

Suzanne Morrissey, 92C, was among a group of Emory Wheel staffers who studied journalism fundamentals with Sitton. Working late nights at the student newspaper made it hard to make a class that met at 8:30 a.m., but "there was no way we would miss the chance to take a class with him," she recalls.

One morning, after an all-night production of The Wheel, Morrissey overslept. Exactly one minute after the class ended, Sitton called her, requesting a meeting in his office in 15 minutes. "Suzanne, are you majoring in English or are you majoring in The Wheel?" she recalls him asking.

"We called him 'a journalism god,' and for good reason," says Morrissey, who now edits a college alumni magazine. "You knew it was a privilege to be learning from him. It was a gift to be in his presence."

"When someone who had that much influence on you passes, it really brings back to mind the reason you went into this business in the first place and how much they inspired you," adds Morrissey, who recalls Sitton helping her secure her first newspaper internship, too.

Legacy of service

Following his work covering the civil rights movement, Sitton served as The New York Times national news director from 1964 to 1968. He went on to become editor of The News and Observer of Raleigh, North Carolina — where he won a Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 1983 — and vice president and editorial director of The News and Observer Publishing Company until his retirement in 1990.

Sitton was one of five Emory alumni to be awarded a Pulitzer Prize, and the only one to win it for achievements in journalism, rather than history or biography, says Gary Hauk, vice president and deputy to the president of the university.

"One of those other Emory Pulitzer winners was the great C. Van Woodward," Hauk recalls. "Like Woodward, Claude was a Southerner who had a different take on race and on the South's narrative about itself."

"Claude's courage in telling that other side of the story earned him the respect of a generation of reporters and the lasting esteem and gratitude of his alma mater," he adds. "He was a fearless teller of truth and afflicter of the comfortable."

Among his many professional accolades, Sitton was inducted into the Atlanta Press Club Hall of Fame this past November. A longtime resident of Oxford, Georgia, he was recently a resident of Emory's Wesley Woods Center.

Sitton also received the George Polk Career Award for journalism in 1991 and the John Chancellor Career Award for excellence in journalism in 2000.

Out of respect for Sitton's wishes, there will be no public memorial service and the family requests no flowers. For those who wish to contribute to a memorial, information will be forthcoming.