Each time Emory Assistant Professor of Religion James Hoesterey teaches a course on “Islam, Media and Pop Culture,” his syllabus takes new turns, constantly fed by fresh examples within an ever-changing media landscape.

But in early January, when terrorists murdered 12 people in the offices of French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo just days before his spring-term class was set to begin, Hoesterey knew he would be revising his curriculum, once again.

In a class that focuses on how various uses of media impact religious identity, authority and experience in Muslim societies, international coverage of the Charlie Hebdo attacks would offer a timely perspective.

In fact, the topic of religion and satire would become a focal point the first day of classes. The French newspaper had a history of attracting controversy, and its irreverent cartoons featuring the Prophet Muhammad had allegedly prompted the terrorists to launch a shooting spree.

“I started off by saying, ‘What’s going on in the news right now?’ and everyone raised their hands and I knew we had to first deal with reports of the Hebdo killings,” Hoesterey recalls.

Although cartoons depicting the prophet Muhammad might seem unfathomable in Muslim countries, Hoesterey led a wide-ranging discussion that day that sprang from an essential question: Are Muslims allowed to laugh at themselves?

The answer, he says, is an enthusiastic, “Yes.”

Can Muslims take a joke?

From ancient writings and modern political cartoons to edgy parodies that can now be found in YouTube videos, there’s plenty of evidence to suggest a robust tradition of Muslim satire, says Hoesterey, who is a cultural anthropologist by training.

Muslim poets and authors have been producing irreverent writings about their own religious imagery for centuries, he says.

“There seems to be this idea out there that somehow satirical images have been forever forbidden in Islam,” Hoesterey says. “That by no means accounts for 1,400 years of history.”

Although today’s readers probably won’t find many Charlie Hebdo-style cartoons poking fun at the prophet within a majority of Arab and Muslim communities, Hoesterey helps his students evaluate not only depictions of the Prophet Muhammad in popular culture, but examples of humor that can be readily found in music, blogs, magazines, theatrical clips and social media.

And the targets of satire are all over the map, including topics such as ISIS propaganda, the Saudi practice of not allowing women to drive, satirical finger puppet skits that mock Syria’s Bashar Al-Asad, and YouTube stars who specialize in political satire and slapstick — even somewhat taboo brands of comedy that are “perceived as tarnishing Islam’s image.”

“We’re trying to dislodge the idea that Muslims can’t take a joke,” he explains.

Islam in America

Hoesterey is intrigued with the perceptions his students bring to class based upon how they’ve seen Muslims portrayed in mass media — an area he encourages the class to explore more fully.

“I like to turn the lens on how Islam gets talked about in America, Atlanta and even Emory,” he says.

Not surprisingly, Islam isn’t always portrayed positively in the Western press — a bias that was firmly in place long before 9/11, an event many of his students are actually too young to remember, he notes.

“Some stereotypes about Islam and violence go back centuries,” he says. “The danger of buying into extreme views is that it flattens Islam and Muslims in a way that doesn’t do them justice or allow for complexities.”

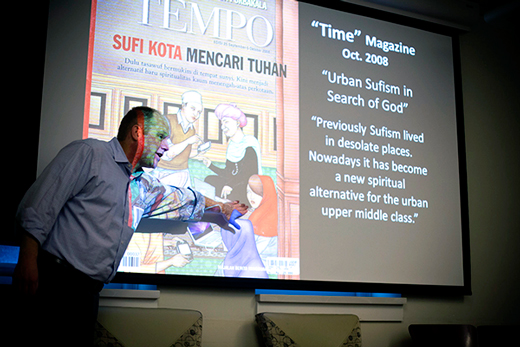

For the class, Hoesterey utilizes “media” in the broadest sense, embracing not only the use of oral and print traditions to spread Islamic teachings, but also the more recent profusion of music, cassette and radio messages, television preachers, broadcast news, artwork and the Internet.

He also enjoys exposing students to unexpected media portrayals that don’t always receive widespread attention, such as stories about American Muslim women who are savvy entrepreneurs, fashion designers, musicians, and magazine editors; or the history of the first Ford Motor plant in the U.S., which employed Muslims from Lebanon.

One goal of the class is to help students become critical consumers of the news, asking questions such as who is funding misinformation campaigns; how individuals who may or may not have credentials are presented as “terrorism experts,” especially in the U.S; and how it is that some news stories about Islam “get legs” while others never achieve widespread traction.

Usually, the class will attract several Muslim students from a variety of sub-sects each term, which helps deepen discussions, Hoesterey says.

“My goals for the class are humble,” he adds. “My hope is that while they don’t necessarily have all the answers, they’ve started the process of knowing the right questions to ask and to challenge the questions that lead us down the wrong path, which is tremendously gratifying.”