Long before Emory’s innovative new water reclamation facility began harnessing the power of nature to clean and recycle wastewater for non-potable uses on campus, the system was already serving as a living laboratory.

Using adaptive ecological technology to naturally break down organic matter in wastewater, the facility, called the WaterHub, is projected to help Emory reclaim some 300,000 gallons of campus wastewater daily, cutting potable water consumption as much as 35 percent and saving the university millions in water utility costs over a 20-year period, according to Matthew Early, vice president for Campus Services.

"Emory is a leader in sustainability," Early says. "With this facility, we’re taking a major step forward in becoming one of the first in the nation with this technology for cleaning our own wastewater."

Yet even as the facility was being constructed last semester, it was being put into service — Emory students were beginning to utilize it for research by monitoring the changing microbiology of wastewater samples as the new project was ramping up.

Analyzing wastewater samples at various stages of treatment afforded rare hands-on exposure to the very kind of field work many of these students will be engaged in this summer, says Christine Moe, Eugene J. Gangarosa Professor of Safe Water and Sanitation in the Rollins School of Public Health (RSPH) and director of the Center for Global Safe Water at Emory, who co-taught a "Water and Sanitation in Developing Countries" course last semester along with Amy Kirby, research assistant research professor in Global Health at RSPH.

"It provided the experience of collecting real data, interpreting results and writing reports," Moe says. "For some students, it may have been the first hands-on lab experience that they’ve had."

In addition to reducing campus water consumption and costs, Moe sees the facility providing exciting possibilities for research, scholarship and water conservation applications far beyond campus.

"One of the things we talk about in class is the growing problem of water scarcity around the world — globally, we’re running out of water," she explains. "Water scarcity will be one of the defining issues during the lifetime of these students."

The chance to engage in research during the start-up of the new facility places Emory students "on the cutting edge of a global revolution," Moe asserts.

"As a large institution, we use a lot of water and we generate a lot of wastewater," she says. "We can control that and show innovation by demonstrating smart water conservation and reclamation to the next generation and the Atlanta community. And this facility presents the perfect opportunity."

A liquid revolution

That revolution is literally taking root in a sleek new greenhouse just off Peavine Creek Drive near Emory’s baseball fields.

It’s the first stop in a water reclamation system that utilizes adaptive ecologics, a natural biological treatment method, to clean and re-purpose campus wastewater, explains Brent Zern, assistant director of operational compliance and maintenance programs for Emory Campus Services.

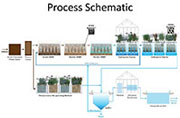

The WaterHub, developed by Sustainable Water, a provider of water reclamation technologies, starts the reclamation process by diverting wastewater from north campus buildings into the first of two distinct units.

Raw wastewater first enters tanks at the 2,200-square-foot greenhouse facility, where it is hydroponically filtered and circulated throughout a dense curtain of real and synthetic plant roots — imagine an intricately woven afghan — suspended throughout a series of aerobic and anaerobic underground chambers, Zern says.

From above, it looks like an attractive botanical garden, with lush beds of native and tropical plants set alongside a burbling fountain. The only odor is the soft, earthy scent of growing plants, typical of any greenhouse.

Below, those plant roots are hard at work, supporting an industrious ecosystem and critical microbial habitat — home to thousands of microorganisms that naturally digest the organic matter in the wastewater with minimal use of chemicals and energy, Zern says.

Those root-dwelling microbes consume the very kinds of organic materials commonly found in wastewater. "This is a proven technology — basically Mother Nature tweaked with some engineering concepts," Zern explains.

The water then flows downhill to another 1,800-square-foot hydroponic installation just across Peavine Creek Drive behind the Beta Theta Pi fraternity — outdoor concrete planting beds that continue the same microbial breakdown alongside a small tidal wetlands system demonstration project.

Water returns to the greenhouse for final treatment, a kind of "polishing" required by the state of Georgia. "It goes through a UV-light sterilization process to kill anything that might possibly remain — a standard requirement — and the county has asked us to also add a bit of chlorine," says Zern, stressing that overall, the process requires very little chemical treatment.

All together, the water reclamation cycle takes about 18 hours, he says.

Conserving regional drinking water

Once treated, the water will replace liquid now being lost through evaporation at Emory’s steam and chiller plants and will help flush toilets at Raoul Hall, says Zern, who emphasizes that the reclaimed water will not be used for drinking.

"We looked at where we currently use the most potable water in our facilities — applications where we don’t really need drinking-water quality water — and it came down to our toilets, our steam plants and our chiller plants," he explains.

Because it takes a few months for the WaterHub’s plant root system to become established to the point where it can provide necessary treatment, Zern says the facility will not be fully operational until later this spring, with a formal ribbon-cutting ceremony planned for April or May.

Using reclaimed water for even some non-potable functions is projected to save Emory nearly 110 million gallons of potable water per year. "And because we’re not using that drinking water, the county can use it other places, which is important for a region prone to water crises," Zern notes.

The new WaterHub also treats a tremendous volume of wastewater within a relatively small footprint, he adds. Reducing the amount of campus-generated wastewater that was being piped miles away to DeKalb County wastewater treatment facilities offers another layer of energy savings, he adds.

Ciannat Howett, director of the Office of Sustainability Initiatives at Emory, sees the WaterHub as an important next step in Emory’s long-term water conservation strategy, which already includes low-flow, dual-flush toilets and collecting rainwater for use in campus irrigation and toilet flushing.

It also helps address a growing problem, Howett says. Atlanta relies upon the smallest watershed in the nation for a metropolitan area of its size. Globally, the demand for fresh water is projected to outstrip availability by nearly 40 percent by 2030, she adds.

"This (facility) offers an interesting case study for how an institution can move a community toward a bold step in water conservation," Howett says. "It’s also exactly the kind of reduction we need to see in order to support a more sustainable future.

"I think it also shows an important role the university can play in advancing sustainability and engaging in this idea of the campus as a living laboratory, a place of experimentation and engagement and learning."

Emory is a nationally recognized leader in sustainability practices, with initiatives that range from award winning green building and recycling strategies to energy conservation. For more information, visit sustainability.emory.edu.