Small differences in as many as a thousand genes contribute to risk for autism, a landmark study from a large consortium including Emory researchers has found.

The study, published Wednesday in Nature, dramatically expanded the list of genes connected to autism spectrum disorder. A 37-institution research team -- the Autism Sequencing Consortium -- examined rare genetic differences in more than 3,800 people with autism and almost 10,000 controls of the same ancestry: by far the largest number to date. A companion study published in the same issue of Nature analyzed 2,517 families with a child affected by autism, relying on the Simons Simplex Collection.

"These findings tell us that there are a relatively large number of genes that, when damaged, substantially increase an individual's chance of developing autism," co-author David Cutler, PhD, assistant professor of human genetics at Emory University School of Medicine, told HealthDay. "Autism does not have one cause, but a very, very large number of potential causes."

The Autism Sequencing Consortium study was led by Joseph Buxbaum at the Seaver Autism Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt Sinai in New York and Mark Daly at the Broad Institute in Massachusetts, and included Cutler and Michael Zwick, PhD, associate professor of human genetics, from Emory.

"This study clearly demonstrates how open data sharing and large, well-phenotyped patient collections can be used to reveal important aspects of human biology,” Zwick says.

The researchers used a technique called exome sequencing, scanning the protein-coding part of the genome. Researchers were able to assess the effects of genetic differences inherited from the parents and those that occur spontaneously when sperm and egg merge.

While small, rare genetic differences in the top 107 genes were found to confer a relatively large jump in a person’s risk, many more changes in other genes add smaller amounts of risk. The new study was also the first to compare the effects of the rate of different classes of mutations between girls and boys with autism spectrum disorder.

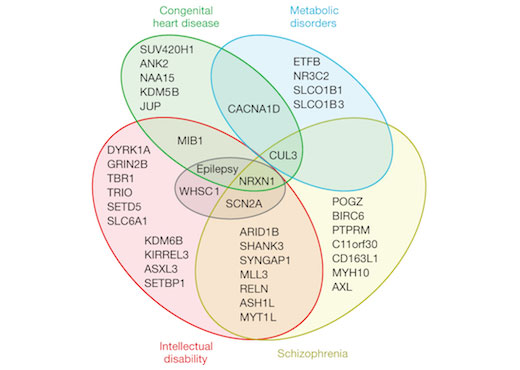

The biological implications of the study’s findings are just beginning to be revealed. The genes identified fall into three main classes: genes involved in chromatin remodeling, transcription factors and genes affecting brain cells’ synapses. The newly expanded list of autism genes overlaps with those linked to conditions such as schizophrenia, says Chris Gunter, PhD, associate professor of pediatrics at Emory and associate director of research at Marcus Autism Center, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

Neuroscientists will need to tease out how combinations of genetic changes can steer brain development.

“If changes to the same gene's function can produce either of these two quite different conditions, how do we get one versus the other?" she says. "And how do either of these two gene sets overlap with what we will see when we look at genetic changes in autism which do not break the entire gene, but instead produce subtle shifts in gene function?"