Forty-one years ago, Professor Ronald Schuchard found himself on the literary hot seat, sitting in the London flat of acclaimed poet and writer T.S. Eliot undergoing what might politely be described as an academic grilling at the hands of the late-author's wife, Valerie.

What was his interest in Eliot? What was the focus of his scholarship? What literary critics did he admire and which ones did he think were full of hot air?

Schuchard, then an associate English professor at Emory University, was already earning strong credentials as an up-and-coming scholar of both Eliot and modernism. As an undergraduate pre-med major, an introduction to Eliot's poetry had affected him so deeply that he decided to pursue a second degree in English literature; later, his doctoral dissertation would also focus upon Eliot.

To be in Eliot's home that evening, surrounded by photos of the celebrated poet alongside the literary luminaries of his day, was an exhilarating, almost otherworldly experience for the young academic.

Since the writer's death in 1965, virtually no one had access to his private papers and personal archives — the result of Eliot's own directives, which his widow had taken firmly to heart.

Schuchard had worked for three years simply to meet Valerie Eliot, who was perceived as something of a dragon lady within literary circles for her fierce protection of her husband's works, widely acknowledged as among the most influential writing of the 20th century.

It was only through a discreet letter of introduction, provided by literary critic and fellow Eliot scholar Professor Dame Helen Gardner, that Schuchard had won an invitation to meet with her.

After the evening's interrogation, Eliot's widow studied him. "Well then, what do you want?" she asked.

"I want to see your husband's Clark and Turnbull Lectures," Schuchard replied.

It was no small request. Eliot's eight Clark Lectures, presented at Trinity College in Cambridge in 1926, and their revised versions, presented as the Turnbull Lectures at Johns Hopkins University in 1933, offered critical, untapped insight into the writer's deep exploration of "metaphysical" poetry.

They had also been produced at a pivotal moment — just before the American-born Unitarian converted to Anglo-Catholicism and chose to become naturalized as a British citizen. For decades, the lectures had been seen by almost no one.

In fact, since Eliot's death, Schuchard estimates that as much as 90 percent of the poet's prose had remained uncollected, out of print, unseen and unavailable to the both the public and scholars.

But on that night, much to his surprise, Valerie Eliot gave her tentative consent: "You may see them, but you may not quote from them."

Eliot's prose: A world long obscured

For Schuchard, the opportunity to examine those lectures would be the start of something big — a warm, enduring friendship with Eliot's widow that would eventually open a world long obscured: the largely unseen personal archives of T.S. Eliot, a treasure trove of his unpublished prose, including his correspondence, lectures, essays, notes and drafts.

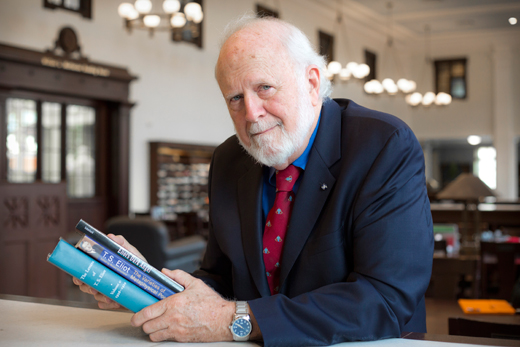

After seven years of research, this month marks the publication of the first two volumes of "The Complete Prose of T.S. Eliot: The Critical Edition," part of a landmark eight-volume project shepherded by Schuchard, Goodrich C. White Professor of English Emeritus at Emory, who served as general editor of the series.

Once completed, the project — which will feature both hard-copy volumes and a fully searchable, integrative digital edition — will corral a massive literary archive, incorporating all of Eliot's essays, reviews, lectures, commentaries and letters to editors, including more than 700 uncollected and 150 unpublished pieces from 1905 to 1965, according to Schuchard.

To mark the occasion, Emory hosted "T.S. Eliot Redivivus," a celebration of both the live digital launch of the first two volumes and the acclaimed writer's 126th birthday, on Friday, Sept. 26, at Robert W. Woodruff Library.

Produced through an international collaboration between Eliot's estate, Emory's Beck Center for Electronic Collections (now part of the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship) and the University of London's Institute of English Studies, the groundbreaking collection is co-published by the Johns Hopkins University Press and Faber and Faber, the British publishing house where Eliot worked for nearly 40 years. The works will initially appear digitally on the Project MUSE website at Johns Hopkins.

The first two volumes, "Apprentice Years, 1905-1918" and "The Perfect Critic, 1919-1926," include all of Eliot's surviving prose from his years as a student and literary journalist through his emergence as a critical voice of 20th-century letters. These initial volumes trace his early literary arc, from the writings of a 16-year-old schoolboy to his rise as a literary and cultural critic, an avant-garde poet and esteemed literary editor.

Highlights include essays from Eliot's student years at Smith Academy and Harvard and his graduate work at Harvard and Oxford, including his doctoral dissertation; unsigned, previously unidentified essays published in the New Statesman and the Monist; essays and reviews published in the Egoist, Athenaeum, TLS, Dial, Art and Letters; his Clark and Turnbull lectures, Norton Lectures, Page-Barbour Lectures, Boutwood Lectures; unpublished essays, lectures, addresses from various archives; and transcripts of broadcasts, speeches, endorsements and memorial tributes.

For each volume, Schuchard is joined by a select co-editor. Subsequent volumes will be released in pairs annually through 2017.

Though much has been written about Eliot, Schuchard estimates that "90 percent of what has been written about him has been written without the knowledge of 90 percent of what he wrote."

"The depth and breadth of these new materials is just astonishing," he says. "I believe that they will feed a tremendous resurgence of interest not only around the study of Eliot, but of modernism in the 20th century."

The hunt for Eliot's 'fugitive prose'

The series is part of the larger T.S. Eliot Research Project, which has united academic scholars and literary editors in England and the U.S. in a massive undertaking to organize, edit and annotate the trove of now-released materials from Eliot's private archive, including poetry, plays, prose and correspondence.

Schuchard's early meeting with Valerie Eliot was a bedrock moment for the project. After examining Eliot's Clark Lectures, he had written a note of thanks to the author's widow, stressing how important they were to his scholarship.

He wouldn't hear from her again for 13 years.

In 1987, Schuchard was checking his mailbox in Emory's Department of English when he discovered an airmail letter from London. "I remember your thoughtful letter about my husband's Clark Lectures," Valerie Eliot wrote. "I might ask if you would now like to edit them."

It was a literary triumph — the first material to be released from Eliot's private archive since his death, Schuchard recalls.

Before Eliot died, he announced that he did not want his wife to commission a biographer or release various editions of his letters. Eliot couldn't stand his private archives being published in piecemeal fashion — what he had published in collected form over his lifetime was all he wished to preserve.

When she objected, Eliot relented, on the firm condition that she must supervise all editions..

For the next 40 years, Valerie Eliot devoted her life to assembling his archive, attending auctions and seeking out private collectors to purchase letters and manuscripts in order to track down what Schuchard calls Eliot's "fugitive" prose. She did edit a facsimile edition of The Waste Land and one volume of his letters, but became "overwhelmed by the massive size of the archive to be constructed," Schuchard recalls.

In 2004, while meeting with Eliot's widow over tea, Schuchard inquired if he might see the writer's correspondence with poet Ted Hughes. Though there was little in the file, he did find a letter from Hughes praising her release of Eliot's letters.

A postscript caught his eye: "Now that you've let us have the letters, won't you please let us have the prose?" Hughes inquired.

Schuchard pointed out the appeal to Valerie Eliot, expecting little response.

To his surprise, she agreed, "Yes, it's time."

The rewards of literary sleuthing

It was a breakthrough moment.

"She then commissioned me to help her, for the rest of her life, to gather all of the materials we could find and start bringing out Eliot's complete prose," Schuchard explains. "Since then, we've been at work non-stop."

The timing was perfect. Schuchard received a Guggenheim fellowship to start the work in 2006, working with Emory's Beck Center, which played an integral role in scanning pages of Eliot's original documents and managing scanned and proofread page images as well as the editors' annotated texts.

To Sumita Chakraborty, a third-year doctoral student in English who was intrigued with the project before arriving at Emory and jumped at the chance to help, assisting the Beck Center with the digital documents has offered a fascinating glimpse into one of the 20th century's most influential minds..

"Eliot was a great thinker and literary and cultural critic; there was nothing the man was not interested in," she says. "We now have access to his reviews and essays on virtually every subject — religion, politics, economics, education, the arts. It's like taking the most in-depth survey course of 20th-century events that you can imagine."

In 2012, Schuchard retired from Emory to devote himself to the project, which became a rigorous exercise in literary sleuthing.

Some of Eliot's lectures and addresses had never been published or collected: "He would just toss them in a drawer, thinking that they were part of the ephemera of the intellectual life — he wasn't anxious to publish everything he wrote," Schuchard notes.

Other material offered only scant clues, literary threads that had to be followed. Poring through the Faber archive one day, Schuchard came across a letter written in 1938 from the headmaster of a private boy's school in Cornwall, England, thanking Eliot for his address on Speech Day.

When Schuchard wrote seeking a record of the speech, they knew nothing about it. But plunging into the school's archives, he unearthed a literary publication containing Eliot's previously unknown essay on how to lead a religious and moral life through the example of the French-Algerian saint, Charles de Foucauld.

Writing to other headmasters, he was able to snare four more "prize day" lectures by Eliot that were largely undocumented "and I know there must be more out there," Schuchard laments.

Lectures to the Braille Society. Lectures supporting housing for destitute women. Lectures for the Save the Children fund. Some of the speeches Eliot would leave with his hosts; others would be found buried deep within office files or a newsletter, otherwise unknown, Schuchard says.

To Eliot, these writings may have been casual, throw-away work. But to scholars, "these are the things that show a dimension of his life that we've never before seen, including how active he was in church and civic life, his involvement with charities," Schuchard says.

They also demonstrate how agile Eliot's mind was in so many fields, from theology and finance to world politics. "He really was a public intellectual before we started using the term," he adds.

There were dead-ends and disappointments, but there were also a wealth of "eureka" moments. Evidence in his Faber notes, for instance, demonstrates Eliot's support of a Polish Jew who had escaped from Auschwitz with a manuscript recalling the horrors of a "roll call." Chosen by the Polish community in London as the most trusted "man of another faith," Eliot wrote the introduction to the man's shocking account. Though its publication got tragically lost in the wartime paper shortage, Eliot's introduction emerges from the archive to challenge critics who have labeled him anti-Semitic, Schuchard notes.

All told, it was a thrilling chase.

Praise for a 'model scholar'

At a recent meeting of The T.S. Eliot Society, Anthony Cuda watched as scholars and Eliot experts previewed a digital version of the project, pleased to feel a pulse of excitement building.

"There are hundreds of stories to be told about Eliot and his intellectual commitments, just waiting there in the prose…" Schuchard told the crowd.

Among scholars of both Eliot and modernism, what is revealed in the publication of "The Complete Prose of T S. Eliot" is nothing short of earthshaking, says Cuda, an associate professor of English at the University of North Carolina Greensboro and 2004 Emory graduate who had worked with Schuchard during his doctoral studies and was selected to co-edit the second volume.

For Cuda, participating in the project not only offered a master class in academic editing and annotation — a disappearing art, he says — but also a broader appreciation of the range and scope of Eliot's intellectual interests and the "hectic and harried pace" at which the prolific writer worked..

"That's where we see these deeply canonical pieces in a new light, in the very context from which they've sprung," Cuda says. "That's the kind of living, dynamic power of these volumes, and something Ron impressed upon me."

"Part of the job of annotating is allowing the reader to be immersed in what's going on at the time," he adds. "To reconstruct his intellectual life at the time he is writing these essays was incredible.

Cuda credits Schuchard for his role as a "model scholar" and as a visionary force in driving the project, the culmination of a life's work, which will create a lasting legacy through a permanent and definitive collection.

"We've assembled one of the largest archives of 20th-century literature, and it will continue to grow," Schuchard reflects.

"Before Eliot died he was one of the most revered writers in the world," he adds. "There is a great deal of anticipation about this material. While there are critical attitudes toward him, I think this work will slowly erode uninformed views."

"He didn't lead a perfect life. But he is a major writer, an intellect of our time," he continues. "These volumes are part of a larger editorial project — his letters, the poetry and the drama — that are going to open for the world a totally new perspective."